It is often said that Architecture is the oldest profession in the world. Even before the idea of an architect is conceived, architecture has been an integral part of human society. The fundamentals of architecture could be boiled down to shelter, but it is so much more than a roof over our heads. It is an expression of culture, of beauty, and of the ideals of man.

It is the skill of combining beauty and functionality that an architect possesses that makes him a professional. His skills and abilities are what is sought after by others in realising their needs for shelter. It is with his profession that the architect carries his own set of ethics and integrity, as well as responsibilities – be it statutory requirements in accordance with the law or contractual obligations.

In recent years, much of the architect’s profession is in service to the affluent and the high earning, with many starchitects in the late-20th and early-21st centuries creating gravity-defying and seemingly impossible forms for the wow factor. Yet as the world progresses and develops at unprecedented speeds, many of the issues lurking beneath are coming to the forefront. Architecture in service to the wealthy has displaced and disenfranchised many lower-income classes, with many not being able to afford the services of professionals for help. What becomes the social responsibility of the architect? What is the relationship between the architect and society in general, and not just to the privileged few? What also is the responsibility of the architect towards nature?

These questions were at the forefront of during the interview with Ar. John Koh. With more than 40 years of experience, Koh has been a pillar of the profession with a vast portfolio of projects. He first founded his practice as Akitek Maju Bina Chartered Architects in 1981, which expanded as Arkitek Maju Bina Sdn Bhd in 1997. In 2014, John Koh Architect was re-established with a greater focus on the conservation of the natural and built environment.

Sitting down to talk about the responsibility of the architect, Koh highlighted that the core responsibility of the architect is towards his client. “The mission of the doctor is to cure; it is a mission of restoration. The mission of the engineer is to build; it is one of utility. The mission of the architect is to realise shelter, but also to work with nature. The architect’s mission is to bring beauty to the world and design to be in sync with nature. The engagement with people of all levels of community is a prerequisite in the architect’s mission.” Koh elaborated that the successful delivery of functional or fit-for-purpose spaces and buildings calls for a clear understanding of living and the processes of life. It is important that the design takes into consideration what is best for the client/end-user, community and nature, a design where nature is a partner and not an afterthought. “Laozi said that the reality of the object is its void. It is the void that gives the object its purpose, such as the void of the bowl gives the bowl its purpose. Similarly, with architecture, it is the spaces within and, more importantly, the users of the space that gives the building its meaning,” Koh mused philosophically.

The philosophy of living with nature is also apparent within Koh’s studio/home AirAngin. * Surrounded by lush greenery and water features, the house is an oasis. The house has undergone many changes, adapting to the needs of the users within. No air-conditioning was present in the house, only fans are used to cool the public areas that overlook the courtyard and the city beyond. The long pavilion stretches along the pool, doubling as a studio as well as a gallery.

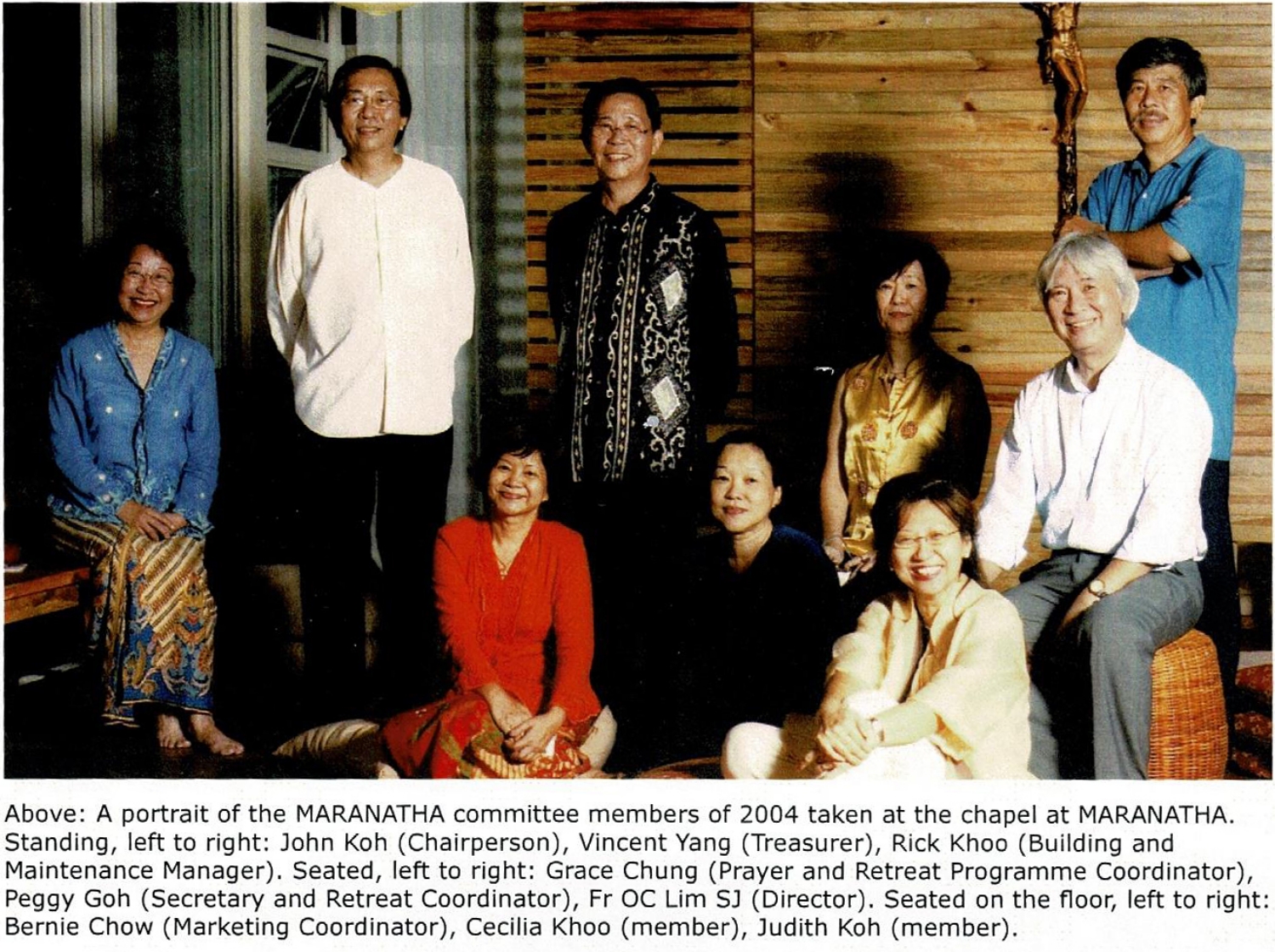

Another example of Koh’s philosophy is his design for Maranatha Retreat House. Serving as a church retreat in Janda Baik, one of the key questions for Koh was how to design with nature and understand the needs of the users. The design makes use of the terrain and gently steps up as one ventures deeper. Surrounded by lush forests, the architecture interacts with its surroundings, adopting local materials and design details that make full use of the site. Stones from the site were used for the cut-and-fill of the terraced landscape. Spaces within have large openings that view out into the greenery, with low-hanging roofs shading the surrounding veranda. Trees that were felled on site were repurposed as construction materials and furniture such as beds and tables for use within the space.

Despite being the architect, Koh is actively involved with the church and has voluntarily taken on the chairperson role of the management committee.This was a recurring theme when discussing the works of Ar. John Koh. Aside from his architectural works, Koh has taken on many roles outside of architecture, mostly voluntary. “I think volunteering is important because it’s doing something you love. These works are pro-bono, it doesn’t mean that you don’t get paid, but you get paid in other ways that enrich yourself.”

To Koh, it is important that humans focus on preserving and adapting buildings for future generations. “Why do we want to retain some of these buildings and facets of the city? It’s because it’s a memory of history, a memory of the people before us. No museum or gallery could truly tell the story more than a functioning, living city.” When asked about his own personal philosophy and thoughts on building conservation, Koh said, “I think conservation is about respect. It is about the mutual respect for the architect that came before, as well as respect for nature and time that has passed. The interface and integration between the old and the new must be sensitively treated. If the addition could not be distinguished from the original building, then I think you would have done a good job.”

Koh was first involved with Friends of Heritage of Malaysia Society, which later became Badan Warisan. Koh frequently led heritage trails with Badan Warisan to educate and bring more awareness towards the public. And why does Koh get himself involved with the organisation? “Architecture is almost always building new,” Koh explained, “and I felt that architects also have a responsibility to preserve, conserve and adaptively reuse buildings. It was an innate sense of social responsibility for me.”

Through his involvement with Badan Warisan, he was acquainted with Tan Sri Mubin Sheppard. The first director of the National Archives, the National Museum, and the Badan Warisan, he was keen on improving the lives of the Malayan community and is highly interested in preserving the heritage and culture of the community. Sheppard called Koh to discuss doing something for his hometown of Malacca.

Koh voluntarily took on the mantle of proposing a conservation plan for the historic zone of Malacca along Sungai Melaka. First presented in 1987, the proposal consists of four parts: the conservation zone, the Sungai Melaka rejuvenation pedestrianisation, the municipal market adaptive reuse, and the preservation and landscaping of Bukit Cina, Bukit St. John and Bukit St. Paul. The main concept was to preserve the green areas and maintain the visual connection to the river and sea. The proposal goes into detail on the significance, conservation priorities and steps in conserving the area. Some of the ideas proposed have been adopted by the local authorities, such as the promenade along the river and the preservation of the old warehouse. Koh said of the proposal, “If you truly believe in a cause, sometimes you could almost manifest it through willpower because you put in that extra commitment to see it through.” He continued to refine his proposal and ideas for the city throughout the years. Recently, Koh published the first edition of his latest plans for the city, titled Restoration of Historical Malacca Landscape (2023). The book expands upon each part of the original proposal, updating with current site conditions and user behaviours. He is currently working on the second edition. “This is a kind of social responsibility driven by an affinity for the place, and I’m very proud of this project.”

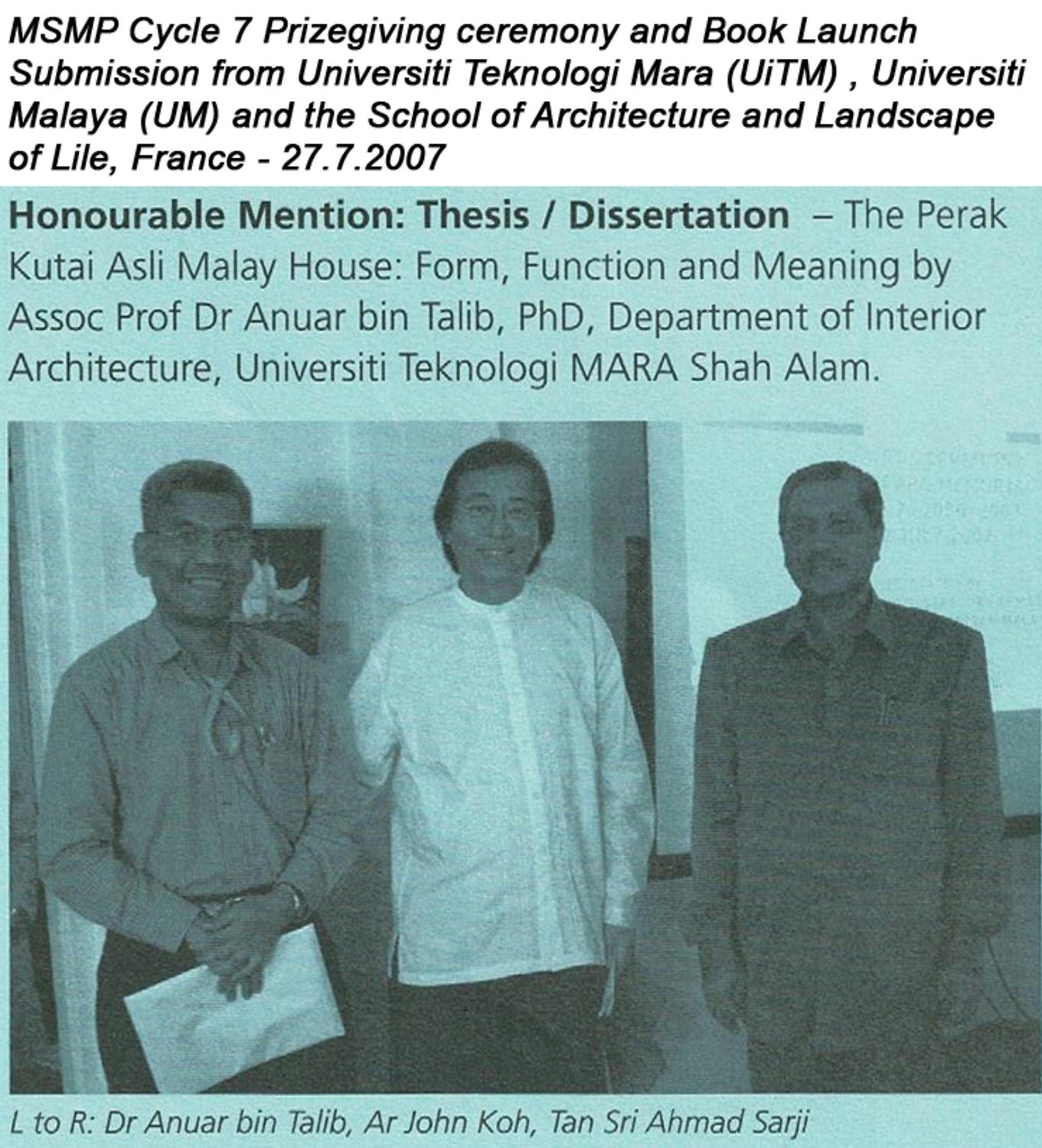

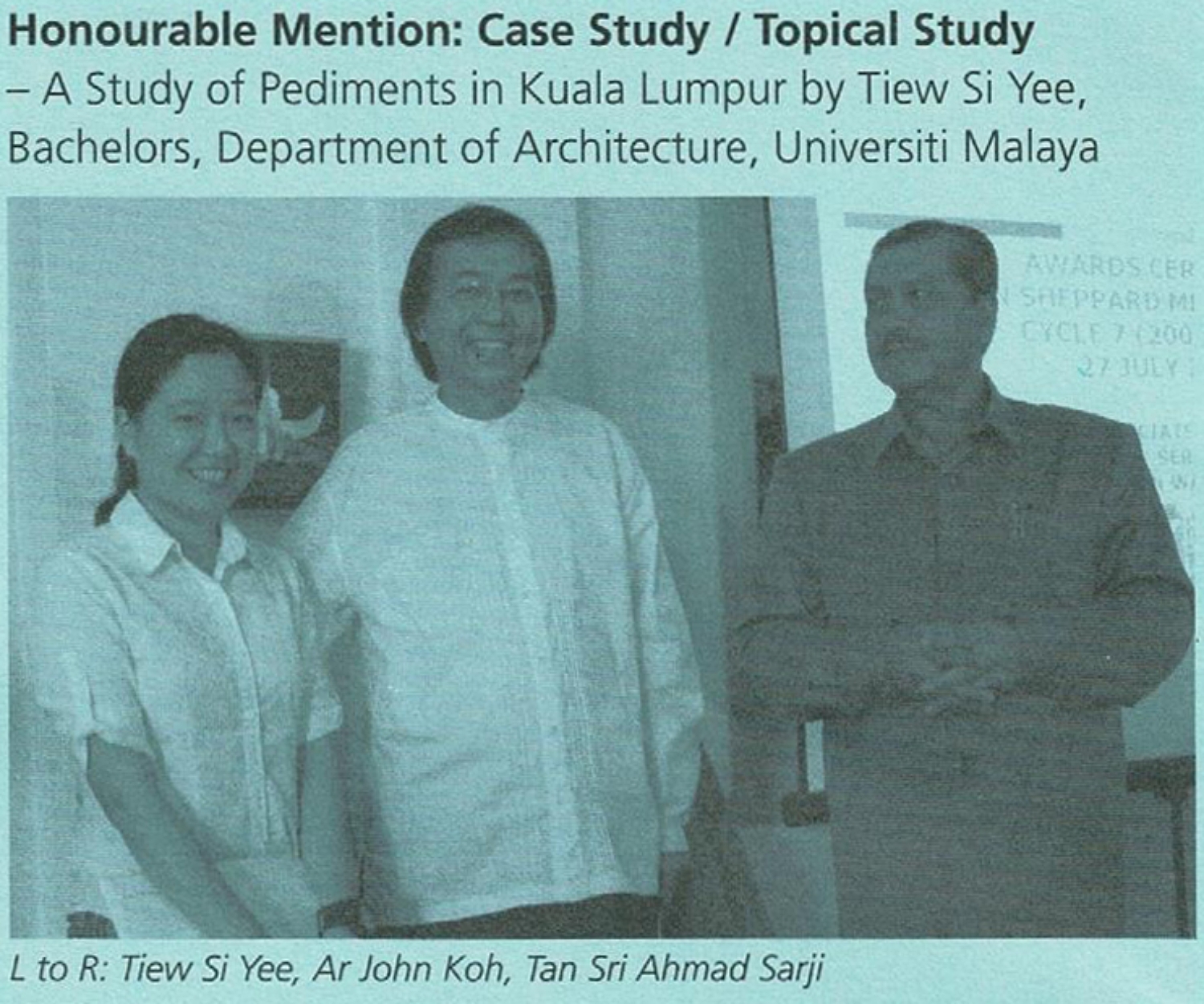

In addition to his Malacca proposal, Koh was also on the panel of judges for the Mubin Sheppard Memorial Prize since its first cycle in 1996, established with the aim of raising awareness among younger members of society about the built heritage of Malaysia. The prize invites students to submit research and writings as well as detail drawings on various aspects of the conservation and preservation of Malaysian architectural heritage. Koh has also personally undertaken several conservation projects, one of which is the conservation of IJ Sisters’ retreat house for the Sister of Infant Jesus in Port Dickson.

Through one of his clients, Koh got involved with another NGO, the Malaysia Nature Society (MNS). The Malaysia Nature Society was founded before the independence of the country by a group of British expatriates who were keen on collecting notes on the lush natural heritage of the country. Founded in 1940, the society has been a leading force in conservation in Malaysia through habitat conservation and environmental education, promoting and ensuring responsible environmental stewardship in the country.

As an avid conservationist with a deep respect for nature, Koh first served as part of the permanent finance committee for the society from 1993, and soon became the chairperson of the board of trustees. Many of the MNS efforts in conservation have been huge successes, the main of which are the gazettal of multiple state parks such as Endau-Rompin State Park, Kuala Selangor Nature Park and the Royal Belum State Park. Much of the society’s efforts in species conservation of the giant leatherback turtle, tapir, hornbill, Malayan Sunbear and many others have also been successful. Koh continues to play a key role in society, with the most recent being advocating for the gazettal of Bukit Persekutuan as a historical and natural heritage and a proposal to reconnect Bukit Persekutuan to two other green lungs of the city, Perdana Botanical Gardens and Bukit Tugu.

In 2020, the society celebrated its 80th anniversary amidst the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown. During the lockdown, Koh, along with members Tan Sri Dr Salleh Mohd Nor, Lee Su Win and Geoffrey Davison, came together to produce a commemorative book titled 80 Years & Moving Forward (2023). ** The hefty 446-page book captures the portrait of the society from its founding in 1940 to the present, including a collection of field notes, essays and reflections from its members documenting the efforts and successes in the long history of the society in nature conservation. The book was recently published in May 2023.

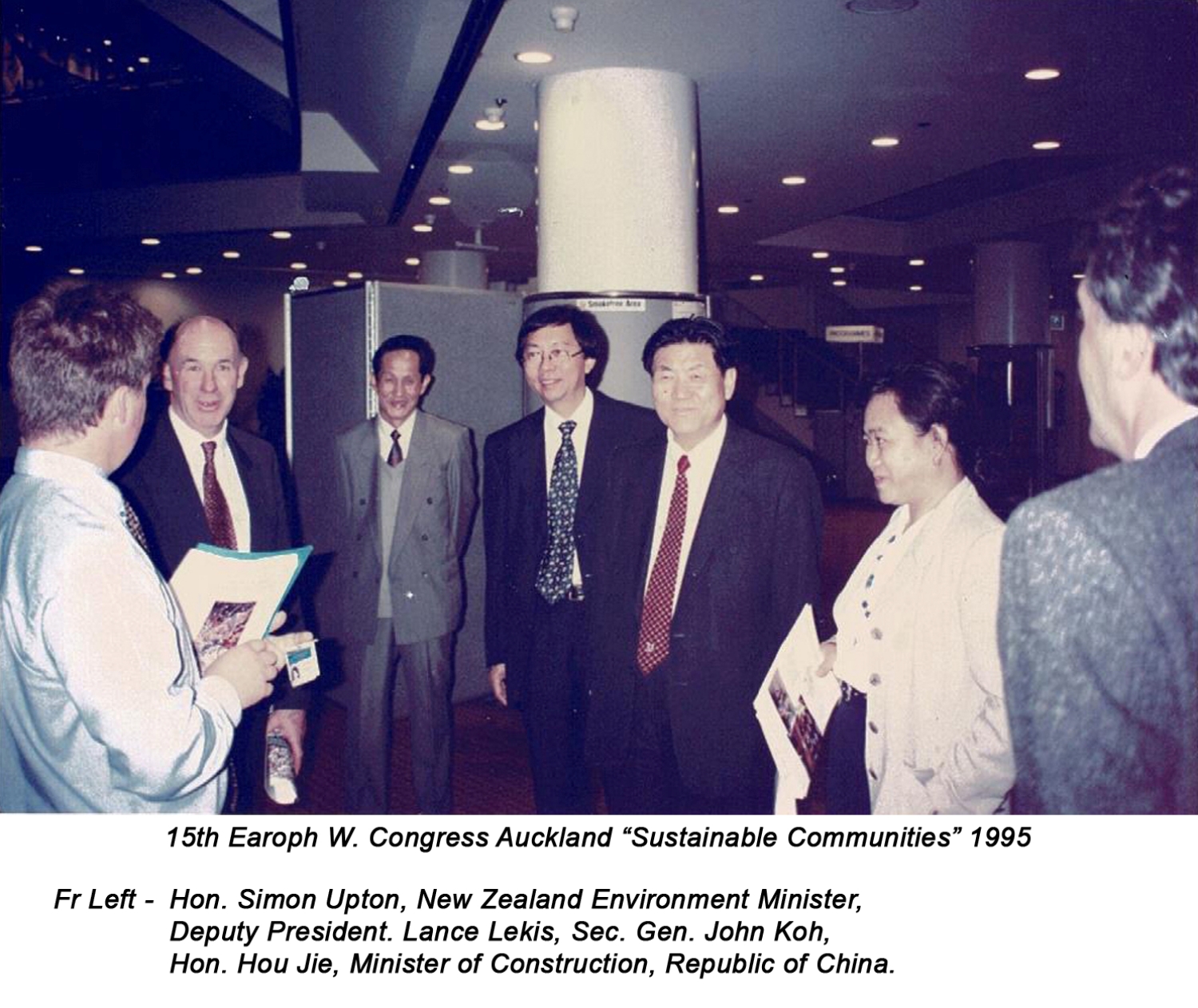

Architecture is not just about individual buildings. Koh believes that architecture involves other aspects of the built environment, including the urban environment and planning. In his career, he continued to explore avenues into housing and planning through his role as the Secretary-General for the Eastern Regional Organisation for Planning and Human Settlement (EAROPH). EAROPH is a non-governmental multi-sectorial organisation focusing on fostering exchange among countries to promote a better understanding of human settlements and encourage excellence in planning, development and management to improve the quality of life and sustainability of human settlements. It was first founded in 1956 in New Delhi, and the secretariat has since moved to Malaysia in 1978. Originally part of the International Federation for Housing and Planning (IFHP) of the United Nations (UN), EAROPH was founded to focus on human settlement development in the Asia and Oceanic region. Now serving as Hon. President, Koh continues to promote collaborations and multi-disciplinary approaches in sustainable human settlements as well as the conservation of the natural landscape in the region.

However, even the most selfless architects have to keep the lights on in the studio, and Koh has his fair share of big-name clients, such as British Airways, Swiss Air, Philips, Nestle, as well as local clients Golden Screen Cinemas and Sunway City Berhad. While these clients may be more economically minded, Koh shares that he takes every opportunity he has with his clients as a chance for exploration. “With every project that I do, I always learn from each of them. For example, I was not only the architect for the Philips headquarters, but we also did the landscaping, the interiors, and the signage design for the company. I was able to exercise a much more complete role in the design and explored many different things in the design.”In the early days he was the designer of the petrol stations for Esso. “I was grateful for that opportunity because I got to travel to various parts of the country through this project. What other project would allow you to design for many different sites at once?”

However, Koh also admits that not every client would be a suitable client. “Not every client is for you. You don’t need to work with everyone, life is very short.” Despite that, Koh still believes that despite clients not having the same agenda for nature conservation and care for the environment, as architects the first duty is always to the client and nature. “To me, the signifier of an architect is your reputation and your works that speak for itself.”

As architecture becomes more accessible, development seems even more inevitable, crucially at the expense of culture and nature. The paradox between progress and preservation is one that is hard to resolve. Koh shares the sentiment. “As architects, we should think globally and act locally. We should always create improvements without uprooting the community. We need to create an enabling environment that uplifts the community alongside development without harming the environment.” It is a sentiment shared by 2023 Pritzker Prize Laureate David Chipperfield, “Architects can’t operate outside of society. We need society to come with us… Essentially, what we have to hope now is that the environmental crisis makes us reconsider the priorities of society, that profit is not the only thing that should be motivating our decisions.”

As the world becomes increasingly connected yet divided, Koh offers his thoughts, “We are in a very unique geographical and anthropological location in that the entire Southeast Asia is connected. Our history, ancestors, language, and culture are connected, from the Philippines to Indonesia to Thailand etc. The identity of the Southeast Asia region is a unique one, one that could be a source of strength for the region. We should strive for regionalism, rather than nationalism; commonality rather than distinctiveness, and make that commonality unique.”

Koh is the regional representative for the RIBA Validation Board and has conducted validations for the University of Malaya and the University of Technology Malaysia. He is also an examiner for the LAM/PAM part III examinations. Looking towards the future, Koh shared his thoughts on the education of architects. “I think institutions currently lack an appreciation for nature. They are leaders in our field. They are at the forefront of our industry, where ideas and experimentations happen. They shape the minds of the next generation of architects that would create the future built environment. It is important that institutions lead and guide the field of architecture with more appreciation and connection with nature.”