With the world dominated by the Internet and social media, and the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI), wabi-sabi brings in a much-needed contrast to the fast-paced lifestyle. Wrinkled sheets, mismatched glassware, heirloom rugs, and not-so-perfect art pieces are just what one needs to bring Wabi-Sabi into their home. Appreciating humble, organic products and approaching home design through a thoughtful sight brings forward its Wabi-Sabi nature. Handmade accessories, modest furniture, natural accents, and authentic colours are all present in a true wabi-sabi-style home. The wabi-wabi style speaks volumes about not needing to follow any design trends and just expressing your authenticity in your space.

The concept of wabi-sabi can relate to duat Japanese Zen Buddhism philosophy which has been deeply rooted in Japanese culture, lifestyle, art, and architecture. The term wabi-sabi 侘) means living in elate to is a combination of two separate concepts of Wabi and Sabi. Wabi (harmony with natural simplicity and humility, imperfections of objects and fulfilling a function rather than a form. It describes contented living with little or less. Sabi (寂) represents the concept of impermanence; both natural and man-made objects experience their own lives as they are created and fall into decay, helping us appreciate its value that much more.

Enso (円相), the Zen Buddhist round symbol is a good example of expressing the philosophy of wabi-sabi. The circle of black ink painted with a thick brush is like an infinite motion, always moving in circles. Sometimes, the circle may be incomplete and have a gap to symbolise everything has a beginning and end. The incomplete circle points out the imperfections in existence and how we should strive to appreciate and understand things at that moment, however imperfect they may be.

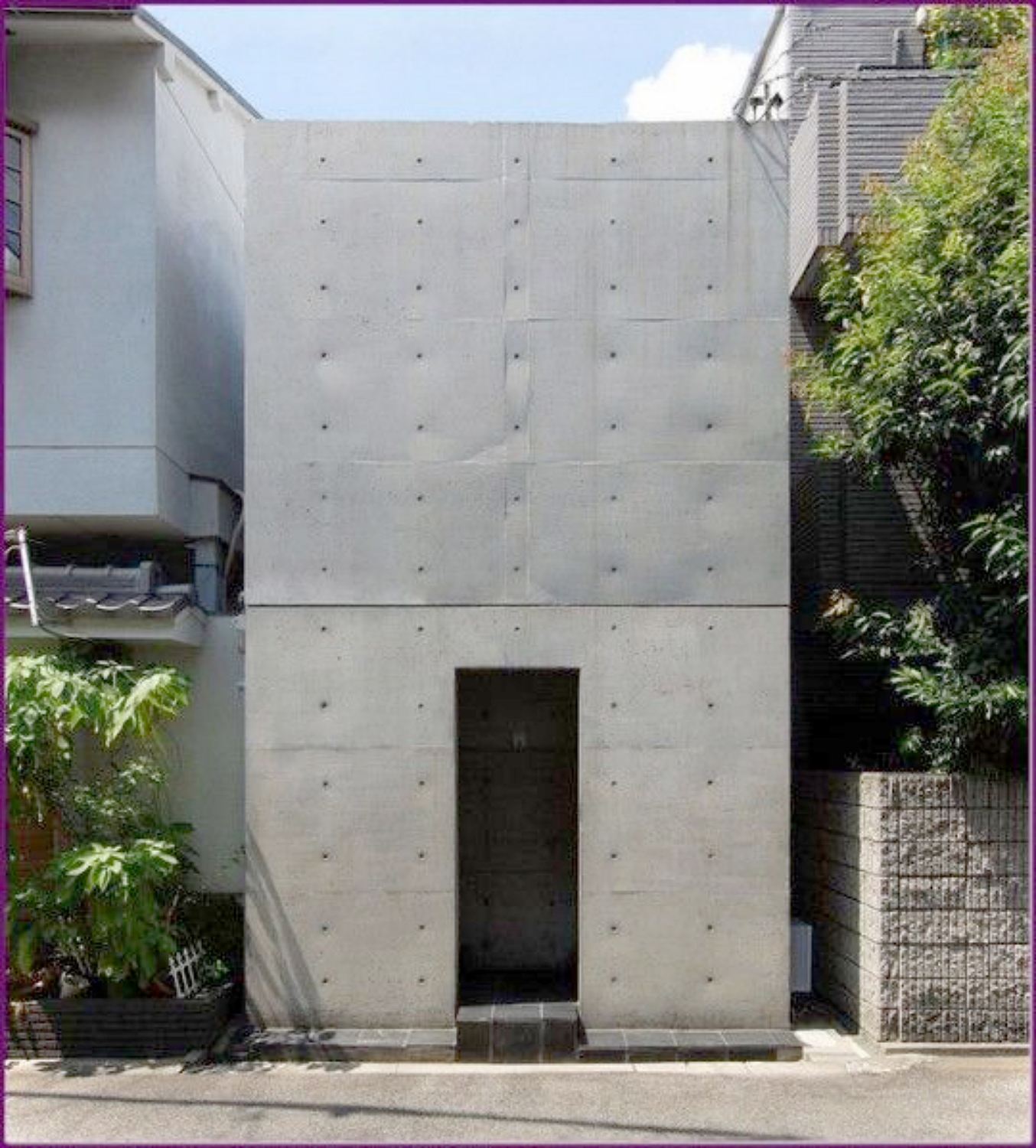

Japanese Architect Tadao Ando describes wabi-sabi as the art of finding aesthetics in the forgotten realm and accepting the natural cycle of growth and decay.

Wabi-sabi is not the valorisation of ugliness but of beautiful objects that seem to approach perfection, only then to veer off at the last moment. Perhaps in this way, they signal that they belong to the world of things and not ideas. It is a worldview that values authenticity, simplicity, and the natural world. Although it originated in Japan, wabi-sabi has been embraced by designers and architects all over the world.

This article will explore the beauty of imperfection in architecture and interior design.

Systematic prefabrication, mass production, fast construction, modular systems; and systematic and fast-paced modern construction have dominated the architectural construction industry. Each project competes with time to completion, mass-produced, and prefabrication offsite. Modern Architecture is about Machines’ ideology, Logical and rational, Universal ideology, romanticised technology, perfection, and precision.

Wabi-sabi’s architecture expresses the opposite. Its interest is intuitive with a personal touch; self-build, romanticising nature, organic formation, natural materials, and construction, adapting to the site and place. The ideology is of impermanence, accepting decay, and the ostensibly crude. The architecture ages with y.anthe abe time, integrated with its weather and surroundings. This means that wabi-sabi architecture is designed to change and evolve, with a focus on durability and sustainability. In a world where so much emphasis is placed on the new and the perfect, wabi-sabi architecture is a refreshing reminder of the beauty of imperfection and the transience of all things.

The art of achieving wabi-sabi, following Wijaya and Zen teachings, is distilled into seven key elements, as follows:

Kanso (簡素) – simplicity, easiness

Fukinsei (不均斉) – asymmetry and irregularity

Shibumi (涩见) – beauty in the understated

Shizen (自然) – naturalness without pretence Yūgen (幽玄) – subtly profound grace

Datsuzoku (脱俗) – unbounded by convention, free, break from routine

Seijaku (静寂) – tranquillity, silence

KANSO (簡素) – SIMPLICITY, EASINESS This philosophy emphasises the use of fewer materials and simpler designs. By eliminating unnecessary elements and simplifying the design, architects can create spaces that are both functional and beautiful.

The concept calls for rediscovering the simple pleasures of life and developing a deeper connection with the earth. The idea is to create a home that oozes tranquillity and peace by designing with simplicity in mind. The architecture focuses on functionality and the basics rather than being overly ornamental and an overuse of materials. The form, space, and material try to return to the basics.

Wabi-sabi architecture is often confused with the minimalism of modern design. These two principles share some similarities, such as plain walls, limited use of decorated fixtures and furniture, views opening to the outdoor environment, and a neutral colour palette.

However, wabi-sabi architecture leans toward humility more than just simplicity. It results from the origin of wabi-sabi in tea ceremonies and Zen Buddhism. Neither does the value of an object lie in the cost of material nor skilful handicraft. The importance is if it can serve its right purpose; a teacup should be able to hold tea; a shelter should provide a liveable space for human beings withstanding

the effects of weather. Wabi-sabi architecture is not the centre of the big picture of nature. Its existence is humble and harmonious with other creatures.

Classical Western and traditional Chinese architecture emphasises geometric order and symmetrical planning and design. On the other hand, Modern Architecture is similar to wabi-sabi in celebrating asymmetrical design.

All things are imperfect in the law of nature. Therefore, universally, nothing is in symmetrical order. When we look closely, things are flawed. The secret to finding beauty in imperfection is to appreciate the intoxicating feelings delusion readily offers, while simultaneously acknowledging them simply as such. This often means using irregular shapes and sizes or incorporating elements that are intentionally offset. By doing so, the design feels less rigid and more organic, like something that has grown and evolved.

Wabi-sabi in architecture embraces imperfection by accepting that all things in this world are impermanent. Instead of approaching architecture with newly manufactured materials, wabi-sabi adopts naturally aged materials such as weathered wood, or rustic metal.

Modernism embraces manufacturing and precision in design and mathematical approaches; on the other hand, wabi-sabi advocates personal touch, intuition and craftsmanship. This kind of approach is only able to be adopted in small-scale architecture.

Wabi-sabi suggests the natural process for materials. They are made of materials that are visibly vulnerable to the effects of weathering and usage. They record the sun, wind, rain, heat, and cold in a language of discolouring, rust, tarnish, stain, warping, shrinking, shrivelling, and cracking. The things that appear odd, misshapen, awkward, or what many may consider ugly are considered wabi-sabi. Inevitable and unavoidable – we are forever surrounded by the crumbling proof of fated existence.Neither the beginning nor the end is perceptible. Naturally, this leaves us empty-handed. Wabi-sabi is the process of process and unpredictability.

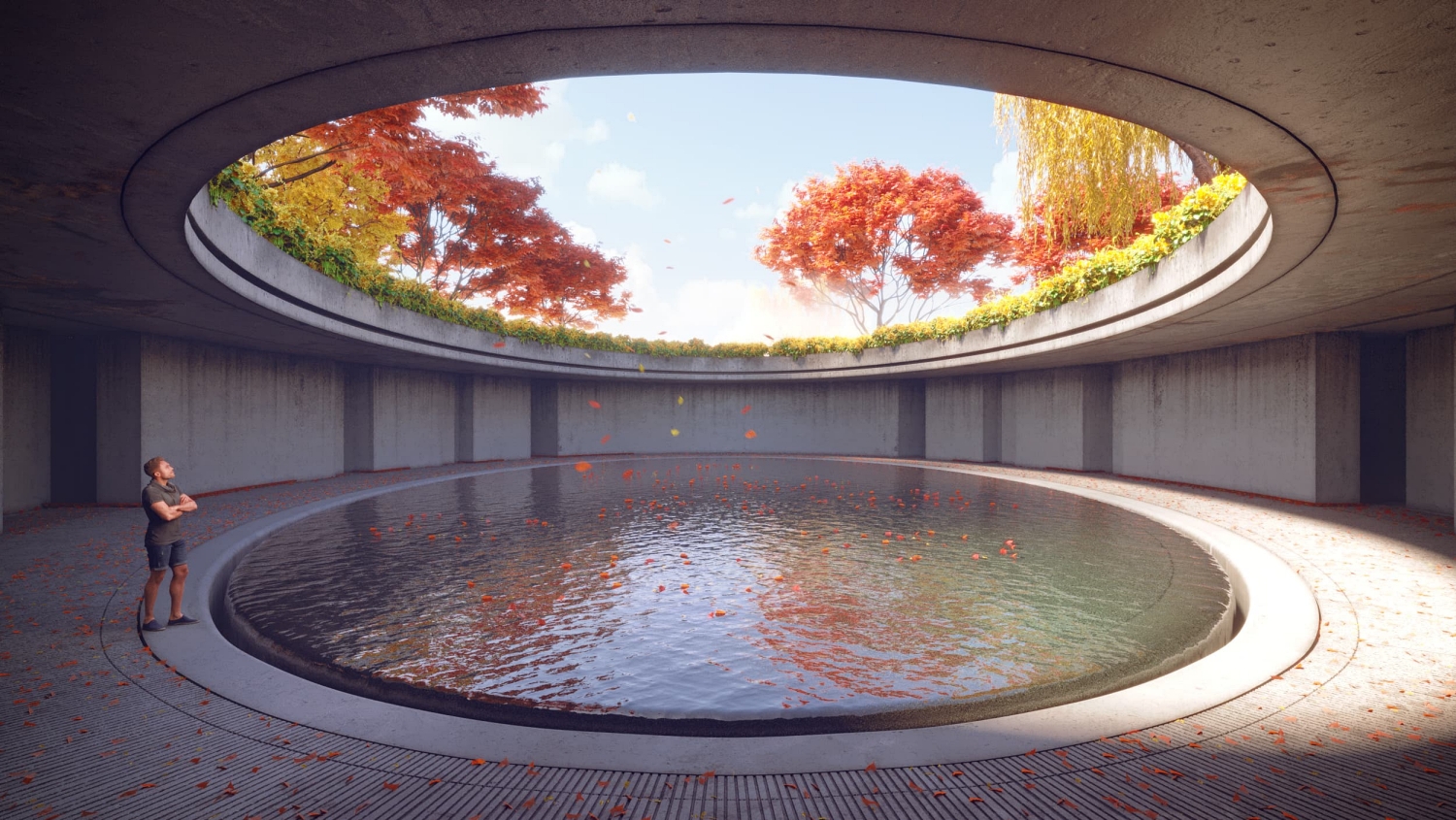

Shizen is a Japanese term that refers to naturalness or ingenuity, valuing the intrinsic beauty of natural materials and processes, and encouraging the appreciation of things in their natural state. The shizen approach is also more sustainable living which engages with natural lighting, ventilation,materials, natural form, and topography.

Architecture adapts naturally occurring patterns and elements into the design, deliberately putting together a seemingly spontaneous artistic creation. Shizen celebrates the natural cycles of growth, including decay and transformation, and sees imperfection, irregularity, and asymmetry as part of their inherent beauty.

In Japanese pottery, an artist might intentionally leave imperfections or irregularities to highlight the clay’s natural beauty. Shizen is also commonly used in Ikebana, an art form of Japanese flower arrangement that must appear as if it were still in the wild. This approach is also prevalent in Japanese product design and landscape design.

Shizen is a manifestation of the wabi-sabi aesthetic in the natural world, reflecting the Japanese belief that everything is connected and that nature is a source of inspiration for art and design.

Through the practice of Shizen, we can develop a deeper understanding of the environment and its delicate balance, which in turn inspires us to live more sustainably and harmoniously.

Yūgen states that the power of suggestion is preferred over revelation – do not show everything in a single impression, instead leave some to the imagination of the viewer. A significant principle in traditional Japanese aesthetics is often difficult to explain in words. In life, design, subtlety, insinuations, and the unknown have a magnetic power, evoking curiosity and thought. Yūgen is often associated with the natural world, particularly with landscapes that evoke a sense of profound mystery and beauty.

After making some room for all the functional items, always leave an abundance of negative space in the process. Create a blank canvas by surrounding yourself with a neutral colour palette – you can easily draw some inspiration from nature itself. The term yūgen is composed of two characters: “yū” which means “dim” or “subtle,” and “gen” which means “mystery” or “depth.”

Unlike wabi-sabi, which emphasises the understated beauty of things, yūgen focuses Tak on the profound and mysterious beauty that lies beyond what is visible or understood. Both concepts celebrate the subtlety and nuance of things, encouraging viewers to appreciate the depth and complexity that lies beneath the surface.

Zen emphasises that opportunities arise from accidental events. In design, the concept of datsuzoku breaks away from convention to give space for exploration. Either in the creative process or the finished product, this tenet teaches that hidden potential surfaces when a mind opens up and welcomes a different perspective.

‘Freeing Architecture’ by Junya Ishigami expresses the freeway for architecture rather than bouncing by strictly architectural order. “Freeing Architecture is the manifesto of an architect who makes dreams come true and those of a society that never stopped believing that functionalism isn’t the only answer. Ishigami presents a true body of works that aim to enhance the desire to free architecture from the constrictions of weight, matter, and form these are his concerns.” For example, the project is a residence/restaurant in Ube, Japan.

Some tend to approach designing a room or space with blinders on – for example, a bedroom is supposed to have these things, so that’s how it will be. Looking at the same space with fresh eyes and envisioning something different may be a challenge, but breaking a pattern is when creativity and resourcefulness “. ardn iteif are allowed to emerge.

Professor Tierney says that the Japanese garden itself, “…made with the raw materials of nature and its success in revealing the essence of natural things to us is an ultimate surprise. Many surprises await at almost every turn in a Japanese Garden.”

Modernism

Logical and rational

Absolute

Universal

Mass-produced

/modular

Future orientated

Believe in control

of nature

Romanticises

technology

Adaptation to

machines

Geomatic formation

Manmade materials

Ostensibly slick

Highly maintained

Express Purity

Clarity and consistent

Cool

Light and bright

Perfect materiality

Permanent

Wabi-sabi

Intuitive

Relative

Personal

One of its kind

/variables

Present oriented

Believe in blending

with nature

Romanticises

nature

Adaptation to

nature

Organic formation

Natural material

Ostensibly crude

Adapt to degradation

and attrition

Express Corrosion

and degradation

Ambiguity and

Contradiction

Warm

Dark and dim

Perfect Immateriality

Impermanent

The wabi-sabi concept in Interior looks forward to authenticity, utilising the connection between the earth and its resources. Preferred originally manufactured materials, artistry crafted versus mass-produced ones.

Apart from seeking authenticity, wabi-sabi also amplifies the usage of natural elements and focuses on raw textures, earthy hues, and organic and natural materials.

Wabi-sabi ethos is a certain reassuring calmness by embracing simplicity in natural form and materials. It’s meant to create a relationship with nature, inside and outside space. Texture and patina are impossible to predict which makes them uniquely flawed and ‘perfectly imperfect’.

Wabi-sabi interior can be summarised through a few of these characters.

1 Less is more

The most important principle of wabi-sabi is simplicity in living and personal items. This is

to strengthen freedom from attachments to material things i n life. Which reduces stress

and anxiety and brings a sense of peace and tranquillity. It’s a response to the lavishness and over-ornamentation in interior design, so it doesn’t come as a surprise that it’s characterised by qualities that are the exact opposite – qualities such as roughness, austerity,simplicity, and modesty.

Using natural materials rather than manufactured ones is the wabi-sabi way. Raw materials like wood, stone, exposed bricks, linen, ceramics, etc provide perfect rustic qualities that are irregular and organic. For example, the interior works inside Falling Water House by Frank Lloyd Wright integrated natural stone on the exterior and interior of the house expressing the ideology of wabi-sabi. Authenticity is a key concept for wabi-sabi, so organic materials and colours play a major part in achieving it.

Aged materials and furniture give memory and tell a story, interior designers can recycle some

of the old materials, furniture, and house daily items either giving another purpose or another touch and giving a new life.

Repurposing furniture and items celebrate imperfection and blemishes which are highlighted instead of hidden away. Also, the uniqueness of the object makes it special and one of a kind. In repurposing items, we include history while giving it a new purpose in our home. And it’s a sustainable way of living.

Kintsugi pottery where the broken pottery is glued back together with gold lacquer. Giving the pottery a new lease of life while highlighting the fact that it was once broken and celebrating the flaws instead of hiding them.

The opposite of every noun in your life is lurking in the shadow with a trick up its sleeve, whether you see it or not is of no consequence. The wabi-sabi state of mind always accepts the inevitable, and appreciation of the evanescence of life. It forces us to contemplate our own mortality and evoke existential loneliness and tender sadness.