So said the Director, Patrick Nuttgens, opening his design lecture when I was an undergraduate architectural student at his Polytechnic in the mid-70s. Verbose and authoritative, he then enthralled the class with a thematic exposition of the Spaniard’s life work projected through celluloid slides whirring in a carousel.

I was impressed. It was one of the first design-theory lectures I had ever heard not that I could differentiate between theory and picture — show at that time in my development. “What is worth remembering,” someone once said, “will never be forgotten, and what is forgotten is probably not worth remembering.”

I am not certain of Gaudi’s import and place in architectural thinking then, but what stayed with me are just a few things: the colourful mosaics, the serpent, wonky arches, and black and white photographs. In practice many years later, and when my mind ran over the memorable lecture, I did at times muse that it would be nice if I could infuse my projects with ‘art’. And for the six long years I spent in the UK, I never saw Gaudi’s work: Holiday money wasn’t easy to come by. I only saw Tuscany and Paris on a school trip (and that was indelibly impactful, in a compensatory way.)

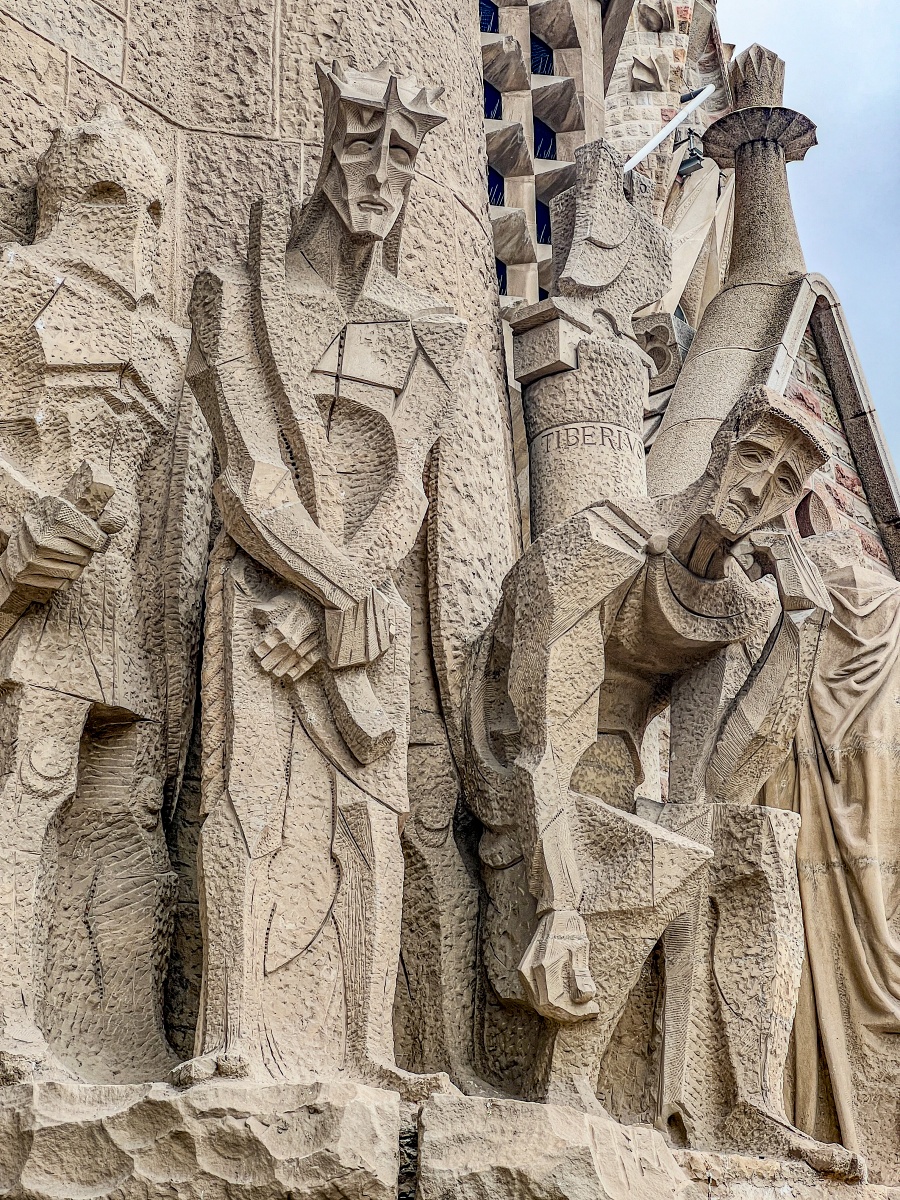

Imagine my excitement then, when, a generation and a half later, one of my students (of sorts) posted delectable shots of Sagrada Familia daily on Instagram and Facebook: He was there! The excitement was less in the resurfacing of familiar images than in knowing that he would return and wouldn’t resist an unpacking meet-up.

With my newly acquired researcher persona, I pre-listed questions with ease: “I do not want any deep technical analysis for this first meeting,” I started. He was already on the same page prior to arriving at Starbucks: “You just want to know why I go there…” “Ya,” I said, “why you go there, what you felt and experienced and thought, that kinda stuff. And then, coming out of it, what are you taking away—I will ask (you) as you go along. (The stuff of semistructured interviews.)

Wong Chee Fon was not only pleasantly articulate; not only did he confidently possess the entire presentation of his sojourn the week before; but, most impressively, he had already reflected on the differentiated value of each of Gaudi’s buildings—scoped to what he had accessed; and had ranked them for touristic worth and architectural significance. Nevertheless, it wasn’t his cognitive control but, rather, his reflexive interpretation of what it all meant to him as an individual that, I feel, contributes a truth reverberating far beyond himself.

It is the time of youth. “Actually, I always wanted to go to Spain,” he began, “because I wanted to visit my favourite football club: It was in Madrid. I also wanted to take a break before hunkering down to serious career development, and Spain is one of the places with the lowest flight ticket prices around Europe (sniggers). So, it was a no-brainer: Why not take a solo trip? And Gaudi was perfect, because it was in Barcelona… So, I finished off the things I needed to in Madrid. Then I went to Barcelona for 4 days and 3 nights.” DeJa’Vu for me: Go cheap.

Taking online advice that the sequence of the experience is important, he started with Casa Mila, “the best among all Gaudi’s houses. Not just in terms of the design. The design, of course: All have their own uniqueness.” Explaining the reality of autonomy, he says that “the managing board of each of these houses differ in their vision on how and what to present of these heritages.” Casa Mila is a visitor centre of Gaudi works, of sorts. “It has a lot of models on a mezzanine just below the rooftop, and the museum approach here explains the ideology and design processes behind Gaudi’s works.”

I feel the lecturer and student have reversed roles. He continues. “Casa Mila was not just showing the effect of the final form but showing segments of different parts of each building. For Casa Batllo, for example, they show you a sectional model and they relate the whole philosophy behind the organic architecture — what Gaudi truly wrestled with in his mind— how he found his form, and how he developed the tower of Sagrada — this was all shown in Casa Mila. It was not shown in Sagrada, weirdly enough. So, if you didn’t visit Casa Mila, Sagrada, will just be another ornament in the city to you?”

So many pedagogical concerns cross my mind: the power of sectional models, the importance of the thesis behind the design, and the iterations in design development before the derivation of the ‘final form.’ No less an observation is the superficiality of architecture to the uninitiated if fleeting aesthetics (Instagram-worthy, notwithstanding) are all that needs consuming. He has certainly been listening in class.

The strength of Chee Fon’s perception emerges more clearly when the second house is added to his narrative. He launches into comparison rather than mere listing.

Casa Batllo and Casa Mila are on the same touristified street, Passeig de Gràcia, and despite popular consensus rating Batllo as the more interesting, Chee Fon disagrees— although he can discern the strengths of each house. “In my opinion, Casa Batllo is not the most interesting, Casa Mila is the best. Battlo is more ornamented and colourful, irrefutably—with a roof that resembles dragon’s scales—while Mila, more restrained, articulates form: An atrium in Casa Mila is just an atrium, no decorations.” Ultimately, Mila has a significantly ‘special interior’ without resorting to gimmicks such as the light show of Gaudi’s portfolio in Battlo. Implicitly, he shows a distaste for kitsch—or what he perceives to be so.

Any architect might be hesitant to criticise a master, let alone a graduate fresh from the books. Chee Fon stutters with his adjectives: “Casa Vicens is basically Gaudi’s first house project in Barcelona. So, it’s a very meaningful project for him, and you could see the (slight pause) naive… naive and, er, immature side of Gaudi there: He was exploring. It’s very, extremely… ornamental, extremely… er, sort of flamboyant in a way.”

From journals and a few books in Central Yorkshire—no internet in those days—I remember Gaudi as being mannered and expressive but never showy or lacking in maturity. Thinking that the young are all enamoured with attention-grabbing modes, I’m amused at his disdain for the overwrought. But he isn’t without his justification. “Like, you know, some details are not necessary, but he overdoes it in that house. Other than that, the house is very controlled and… er… (rethinks) ok, you won’t say it’s too ornamental, but Casa Vicens has this identity of being slightly ornamental. But it’s still nice, still nice.”

Clearly, the young mind is forming an assessment on his feet, listening to his feelings.He has a sharp ear for the significant, too. “Some Americans who visited Casa Vicens at the same time I did remark that this house resembles what Frank Lloyd Wright would do. So, both would design the furniture together with the walls… and things like that —something you might not see in Casa Mila or Casa Batlló. So, Casa Vicens is more… in a way… ‘experimentative’… in a very subtle way.”

He shows a curative mind when he pushes the next two Gaudi works aside as underwhelming and, finally, Sagrada as overly well-known. “Sagrada (smiles) I don’t need to elaborate… haha.”

In his assessment, Park Guell is a failed housing development: “It’s essentially supposed to be a residential complex, sort of like our Malaysian, landed house development. But I think, for some reason, that didn’t happen —maybe budget or something. It became a park.” Park Guell is large, and its natural landscape made a stronger imprint than the two uncelebrated houses Gaudi left in it.

His explanation is unique to himself: “I think a park marries Gaudi’s ideology best—because it’s organic, right? So, you would expect a park project to be the best for Gaudi to showcase his preoccupation. But I felt it was underwhelming in the way that it became too ornamental and manmade. So, it took away the nature quality of a park: The whole thing is no longer a park, it’s just a rich man’s backyard—it felt like that.”

And yet, images from the net show that Park Guell has some of the finest mosaic work of Spanish Art Nouveau—not least, emblematic allusions to a heaving, multicoloured serpent on its roof. It seems that we are diverging in our perceptions, possibly an outcome of differing epistemological contexts: Chee Fon and I belong to different generations—as Patrick Nuttgens and I also did when I listened to his lecture in Yorkshire. Nuttgens was adamant we believe a serpent crawled on the roof, alluding to the Christian theme of good versus evil. Alternative narratives (easily available on the internet) suggest that it could just as well be the Dragon of St. George, referencing the morality of courage and valor instead, of hyping the Catalan spirit. Are there yet other takes?

“There were two buildings in the park,” Chee Fon continues, “one was a house for Gaudi’s father; another, a house for a rich man. But Gaudi wasn’t able to see these projects come alive: He passed away before they were built. So, these two houses essentially were just built by contractors based on his drawings. So, there’s a level of superficiality to that. And then, the significance is that lizard thing.” A salamander guards the entrance to Park Guell.

I understood his logic, barely. The construction of the two houses did not have the touch of the master’s hand, and in that sense was “surface work” interpreted by the hands of mere agents, thus earning the label of superficiality. And, in his mind, (over) ornamentation is a bind. I do not necessarily share the same logic, but the point of ethnography is that we all tell our stories the way we see and feel the pulse of life. Our stories are ours and no one else’s.

As I finish my Signature Chocolate, I must end the conversation quickly to head for studio tutorials. Sagrada, plainly, as he had implied, needed no esoteric, personalised dissection. The sculptured knights, the stained-glass windows with no literal images (Islamic, in that sense), the statues from Christian mythology (in the best sense of the word), and the tree-like columns, were all there on his laptop and well-browsed on the net.

I couldn’t help realising that perceptions are so much a thing of the time. Gaudi (1852-1926), Patrick Nuttgens (1930-2004), I in my sixties, and Chee Fon in his mid-twenties must surely see some things differently, even if we share much. The “lizard thing” is a case in point. Nuttgens had drummed into us the dominant presence of a serpent in the architecture of Gaudi, suggesting that the influence of Gaudi’s Roman Catholic faith might have been the obvious reason. And I wonder if, in that respect, Nuttgens’ own Roman Catholic upbringing might not have persuaded him to be sympathetic to that interpretation. Nuttgens, who obviously made an impact on me, was an academician, artist and architect. He was also a member of The New Churches Research Group (NCRG), a group of Catholic and Anglican church architects and craftspeople who promoted liturgical reform of churches, among whom was Lance Wright, an architectural reviewer whose writing I also respected. Clear of this coterie of influence, Chee Fon saw no mythical creature in Gaudi’s work.

He says, “Lizard has meaning? No, I believe it’s the scale of the lizard Gaudi was fascinated with. Remember, the Casa Batllo roof also had a lizard—snake—as well? Anything reptilian, even Sagrada had it. Not for religious reasons.” The disengagement with ecclesiastical norms, he points out, extends even to architectural planning. Importantly, he relegates the diversion to Gaudi, the architect, and not to himself: “And the plan of Sagrada went away (from the typical-traditional)—I mean it still represents a cross… in some way… but it was trying to represent a reptile as well… a tortoise. Can you see that? This is the head, this is the leg, this is the shell.”

Serpent, dragon, lizard—the readings can stretch from creation to evolution. Such is the power of semantic work. Just when I might have accepted that we belong to totally different worlds, with nothing to share, Chee Fon surprises me when I ask, “What do you think you will take from this tour and experience into how you might want to design in future?”

“So, it’s not necessarily the work itself?” He replies after some thought. “Maybe it’s Gaudi himself. I think it’s the attitude he brought. He’s not doing this based on ego. He’s doing this for expression and for happiness and all that. To strive in this tough career, you must find joy in what you’ve done. I think that’s number one. Number two is that you must find very innovative solutions to build up your happiness. I think what he has shown, apart from joy, is also perseverance, for sure.”

“What do you mean ‘build up on your happiness,’” I ask, sensing that our life values might perhaps meet

after all.

“I mean to live by doing what you like. He must work, right? He is very persevering in experimenting and he’s not afraid to try something that no others have tried. And he is not doing everything for fame. So, he’s really doing it for the sake of enjoyment, reminding us of the happiness of craftsmanship. So, I think that happiness in your work was essentially what I picked up. Not necessarily his projects—his projects, well, they’re aesthetically very flamboyant. But that’s not necessarily what you pick up for your own present career (slight snigger).

“And were you not even slightly like that before seeing his work?” I ask from the weight of personal experience.