The wall has been a part of architecture for almost as long as the idea of enclosure was the basis for imagining buildings.Thus, historiography is supported by sketches of rudimentary dwellings, some of which depict leafy branches assembled as a structure harbouring inhabitable space, even if these early walls do not exclude the elements totally.At the extreme end of this evolution -or at least one of a few extremes -is the relatively contemporary proposal of ultimate wall-lessness in Mies Van de Rohe’s Glass Skyscraper Project, 1922 – glass being the near negation of materiality.

In between these ends of the spectrum, designers have engaged with the wall in countless formulations, and they range from (but are not restricted to) the wall as a projection of wealth and taste – such as the all-too-familiar, ornate Victorian facade; the wall as a reinterpretation of landscape vocabulary in the Stone Wall House for Fernando Pessoa by Filipe Paixao; and the wall as a symbol of emotional recovery in Bach for The Overcoming of a Near Drowning by Wong Wey Jinn.The Victorian architect has the facade impinging onto your senses, the more to force an acknowledgement of your inferiority, the better.Paixao, on the other hand, seeks to camouflage the building in the landscape by borrowing from constituents of the landscape itself: The entire house is a wall, artfully inserted into the meadow as an inflected form.Finally, Wong, an architectural student, narrates a childhood experience of near drowning by emphasising the continuing overcoming of trauma in a dramatic spatial slab of angular form gripping a swimming pool of glass on the first floor.The water filters sunlight into the interior of his Bach.

Closer home to the subject of this article, the Malaysian firm, Formzero, helmed by partners Lee Cherng Yih and Caleb Ong, absorb themselves in this erstwhile conversation on the typological element that is the wall.

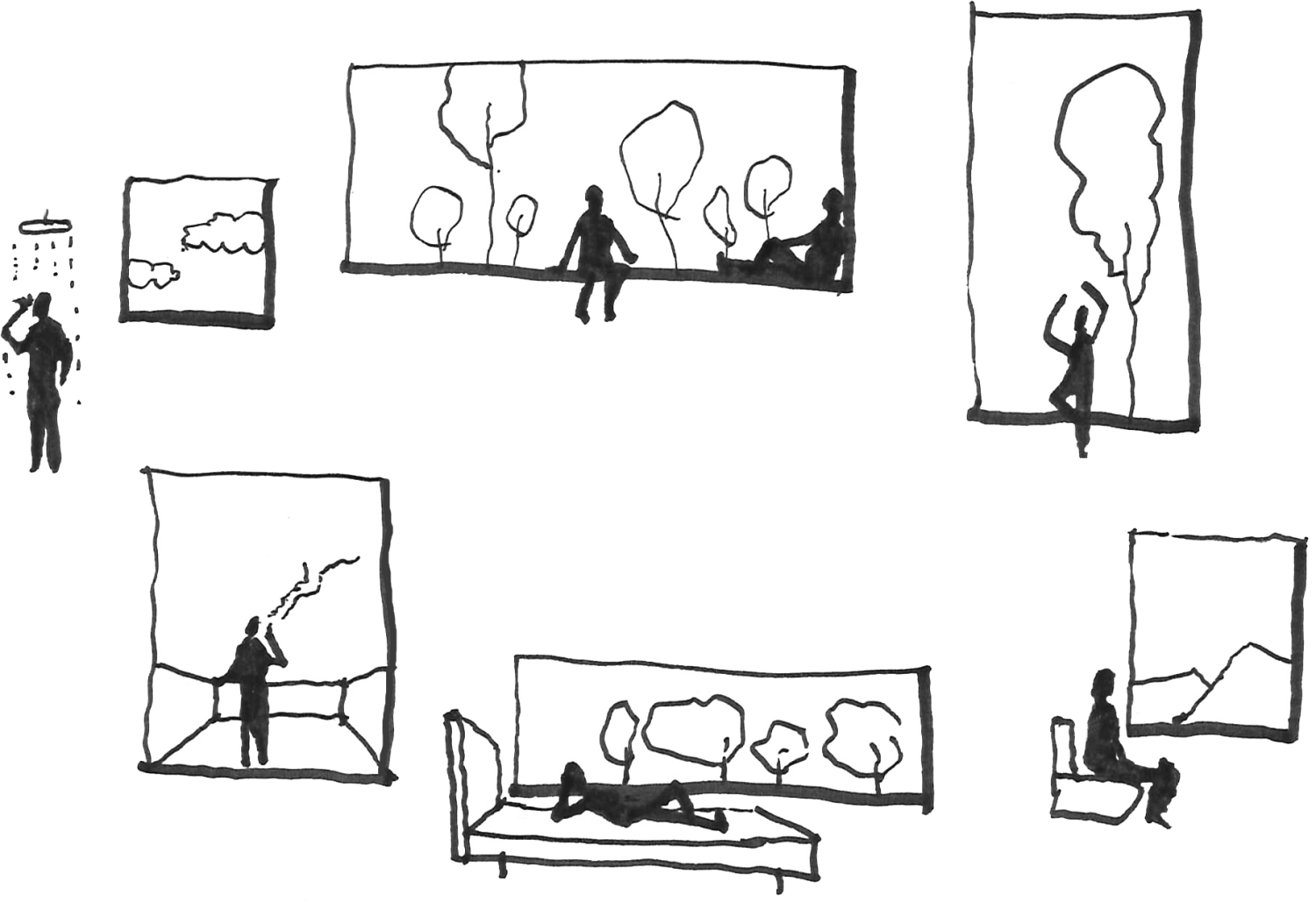

A self-confessed village boy, CY Lee cites the curtain in his childhood home as being more than mere fabric.“The curtain is always dropped down; my mother never opens the curtain; I had no clue what was going on outside.”And this threshold that blurred inside from outside, suspending time in a dim, perpetual present, transpires when he reflects on his Window House, a large, skewed box with curated punctures, designed for a single family in Kuala Lumpur.

Not a fan of planting, the family had to be introduced to the merits of biophilia.“We’ll try it,” they said to Lee’s proposal of a buffer zone of planted pockets of contrasting heights slipped in at various levels to separate the exterior, widowed wall of concrete from the internal skin of generous glass.No window is the same – each is configured in response to individual behavioural and personality needs.In a sense, the design of the wall with windows here is deterministic and not, in Lee’s terms, “patterned to some aesthetics.”Window chamfers, however, give the precedent away -as Lee explains.

“The first time I saw the windows of Ronchamp Chapel (made me think,) ‘Wow, that window creating that light pouring into the space is so beautiful!’ Corbusier’s thick wall creates a sense of depth to the façade, and from that experience, we were inspired to create a thick concrete shell to filter light, privacy, and the heat from the sun.”

Discerning contextual differences prevented replication.It’s the principled appropriation of the design device that gives Window House its own mutation of the wall for purposes of suiting a different user and blending into an original concept of the wall as a sandwich of skins and interstitial air spaces of green.In Lee’s view, “Ronchamp uses a different construction method: There are a lot of hollow walls. But you can nevertheless see where my chamfering of the window reveal is coming from.”

Superficially, the preoccupation with the wall may seem to have been terminated in the transition from Window House to Planter Box House (the latter developed right after the former).But this is because Planter Box House has no walls in the traditional sense, and without walls, there can be no windows.“It has no windows,” asserts Lee.His early sketch shows stepped-back terraced gardens with progressively shortened floors predominating.

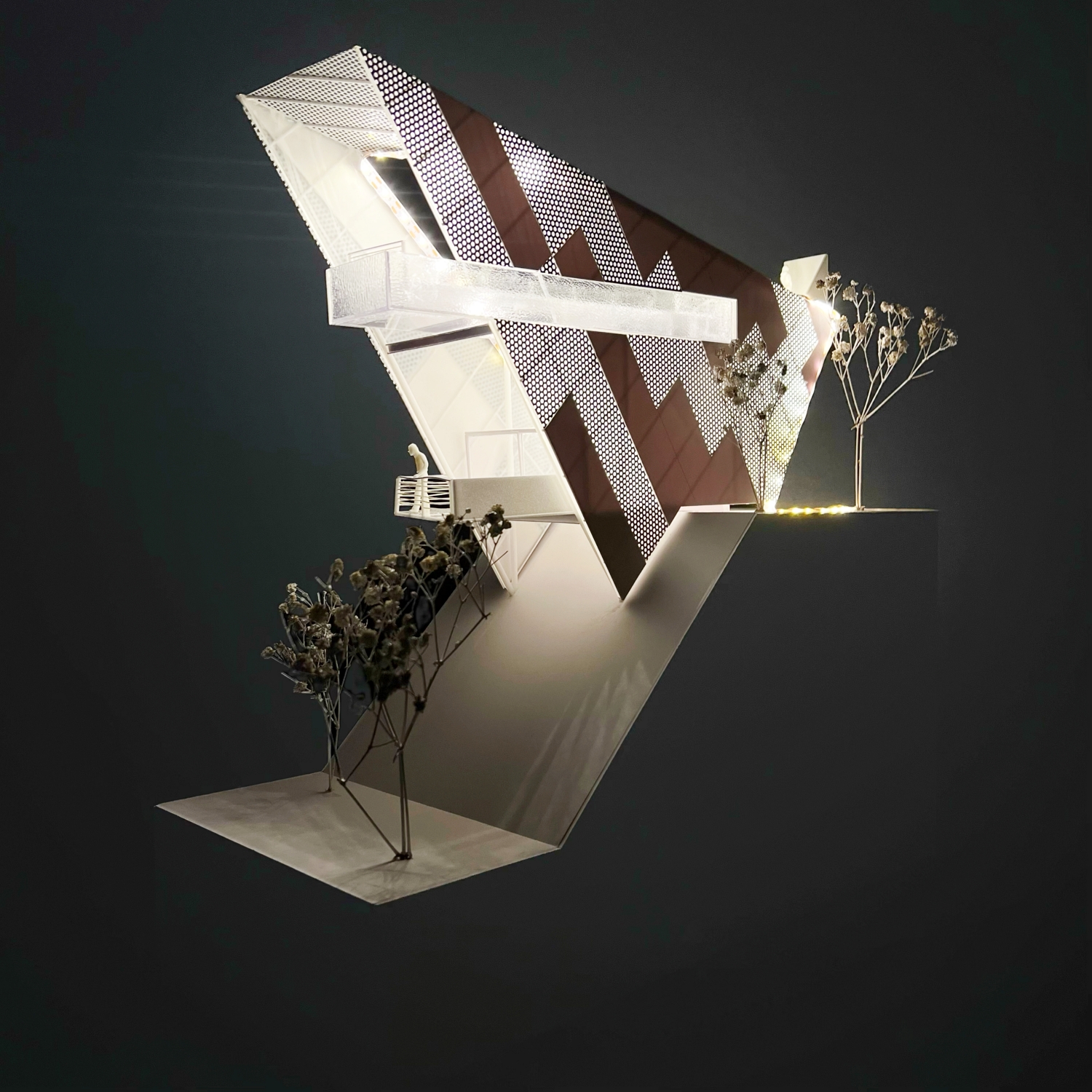

In implementation, however, the standard link house lot of 24’ × 80’ demanded that two “facades” be contemplated.The longer sides, being party walls, caused the focus to rest on the front and rear faces.And there the similarity ends.The rear face is virtually wall-less-steel strings from ground to roof encouraged creepers to grow a drapery – while the front presents the public with an inescapable assault of orchestrated complexity.

The wall is now many things: It is a living tracery subject to time, season, and nurture; and it is a playful stack of concrete boxes for constructive assertion with an absence of windows.The shift is away from regarding the window as a framer of views to theorising the act of looking between inside and outside as a modulator of the wall.

A consequence of the need for planting as a screen – and not as an iconic agenda – the collage of planter boxes transforms the balcony into a landscape typology in its own right – highly varied and multipurposed, randomly positioned in space – instilling an enhanced degree of incident, surprise, and need we say, Instagrammable delight.Within this way of looking at design, new variants to typologies arise, as, for example, the bathroom and extended lounge.“Bathroom with balcony and planter will create an outdoor bathroom so the planter serves as a tall screen wall… benches were sort of designed together with the balcony to function as an outdoor living space,” explains Lee.If a wall is unavoidable in architecture, then the wall is here conceived of as a living zone.

The emergence of a utility quotient does not escape the reflective architect.Lee appreciates the strength of this concept when he compares houses, admitting that the buffer in Window House-for all its elevated drama-could have been infused with greater usability, allowing “the owner to come into this buffer zone to use.”

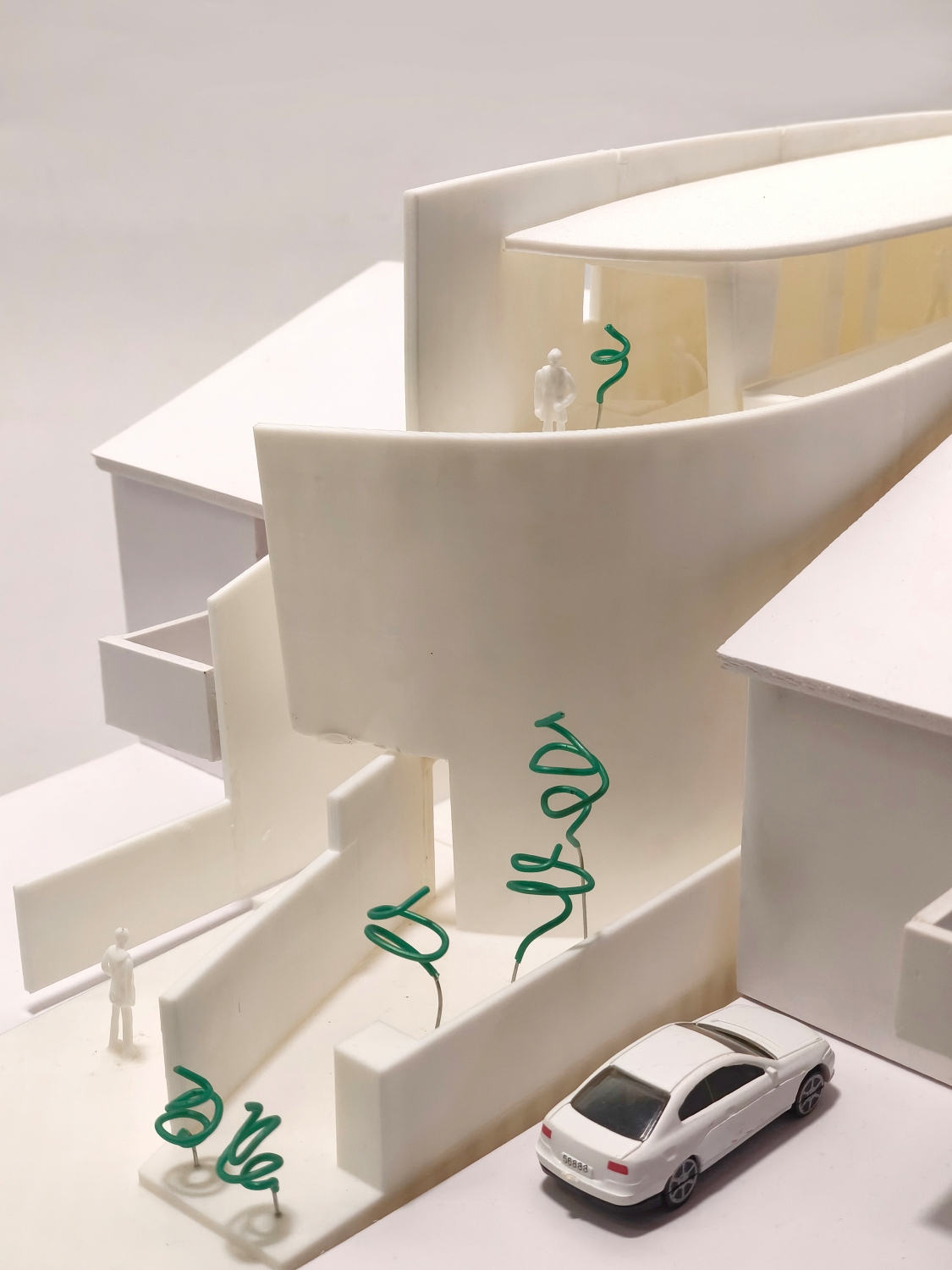

The theoretical trajectory of the wall continued into the third house, Borderless House, in two investigative respects: Firstly, and not unsurprisingly, to scope down tectonics.By this, Partner Ong means ‘to make materials more ethereal, to disappear them, figuratively speaking.’And this is no surprise, given the heaviness that comes to the fore in images of the previous house.Secondly, and this is cognitive to the designer, to question architecture, use, and meaning more rigorously.Ong is specific: In many words, but to the effect, “How can we merge the traditional Chinese garden and Barcelona Pavilion?”How can walls capture a composite of these vastly different precedents?The question seems to be Ong’s unabashed nod towards the effect of visits to Suzhou Chinese gardens and Van de Rohe’s icon of the Modern Movement.

‘A wall sits on top of another wall, and a roof sits on top of the wall, and then another wall extends out in a seamless rectangular way…’ is how Ong remembers the Barcelona Pavilion encounter.“There’s no sense of enclosure. Even though I was within a four-walled compound, the sense of enclosure completely disappeared. I was like, Wow! This sense of wrapped-by-wall… without the confinement of the typical room or house”

In Borderless House, the wall is a performative act, characterised by flux – a choreography of surfaces, and spatial ambiguity.Notwithstanding the admiration, the designer is not naive about contextual differences.Barcelona was “simply a pavilion” with no rooms, whereas Borderless House is a home for an elderly couple with visiting extended family in a residential neighbourhood needing the usual security and air-conditioning.The walls in Borderless are thus kinetic – large panes of glass slide away to ephemeralise them.

Fence walls share indistinguishable materials with building walls, extending the body of the house to the lot parameter, blurring what would otherwise be stigmatised as a barricade that alienates neighbours.Literally, it’s the blurring of boundaries.While enclosure is the main intention in standard fare, Borderless House presents the wall to dissolve elemental differences, extend perspectives, and multiply dimensions.

A CONTINUING PREOCCUPATION

In collaboration with MOA Architects, Borderless House won Formzero Architect the Gold award at the PAM Awards 2025 recently.A pinnacle in professional practice, the achievement is not a decelerator in Lee and Ong’s continued preoccupation with the wall as a design generator in architecture.On the drawing board (so to speak) are interrogations into the wall as unitised components in a de-triangulated house of cards, the wall as a planar wiggle, and walls as a spatial funnel and fractured oculus.They are in various stages of realisation – from speculation to on-site construction.

Critically, Formzero’s window into the wall as a design engagement has not been exhausted.Gestation may test one’s patience on the way to recognition, but that is no cause for ceasing to think and to dream about possibilities.For theoretical architects, this is universally common ground.

Paixao’s inhabitable wall house, for example, is a competition entry not yet built.But like the profusion of explorations in the studio of Formzero, it represents the reality of imagination that precedes materialisation.And the imaginative can glean inspiration from all directions for their design preoccupation.Lee remembers how his mother answered his query as to whether her uncle still lives in his village house that is now covered with unkempt bushes and trees to the extent that the house is risking invisibility.

“’He still lives inside,’ my mother said.

“‘Why all the weed-bushes? And there’s no fence – nothing!’ I asked. ‘It looks abandoned.’

“She said, ‘Oh, he purposely lets the bushes and trees grow until people feel that this house is abandoned and don’t get too close to it. So, it’s his self-defence mechanism.

“‘Wow!’ I exclaimed. ‘That’s such a clever way of landscaping! And it creates this beautiful frontage of green!”The remembrance is subjective and personal.

And it is perhaps this ability to see the theme that unites the disparate that makes Formzero’s preoccupation with the wall worthy of consideration.Disrupting the character of division innate in the wall in architecture, the thinking mind can see beauty in the humble for transposition to contexts which, to the uninitiated, are vastly different.Evolving the wall may be a treadmill of frustrations to some, but to others, the result can sometimes be spectacular, even if seemingly fathomless.

Like the Barcelona Pavilion, which transcends its time through the clarity of its ideas, the wall persists not just as a structure, but as a didactic device, a canvas for ‘What if?’ and ‘Why not?’In elevating the humble wall to a locus of inquiry, the architect reminds us that excellence belongs to those unafraid to interrogate the familiar, finding in process and product alike both illumination and legacy.