The relationship between space, place, and something else forms the poetic foundation of visual storytelling through drawing. When sketching, one is not merely recording what is seen but translating what is experienced. A line, a shadow, a tint of colour, each mark becomes a vessel carrying atmosphere, sound, and impression. Space defines the physical reality before us; place embodies how we feel within that space; and the “something else” is the ineffable layer that connects emotion to form, thought to gesture, and perception to memory. It is the heartbeat of experience, the part that cannot be measured yet gives meaning to all that is drawn.

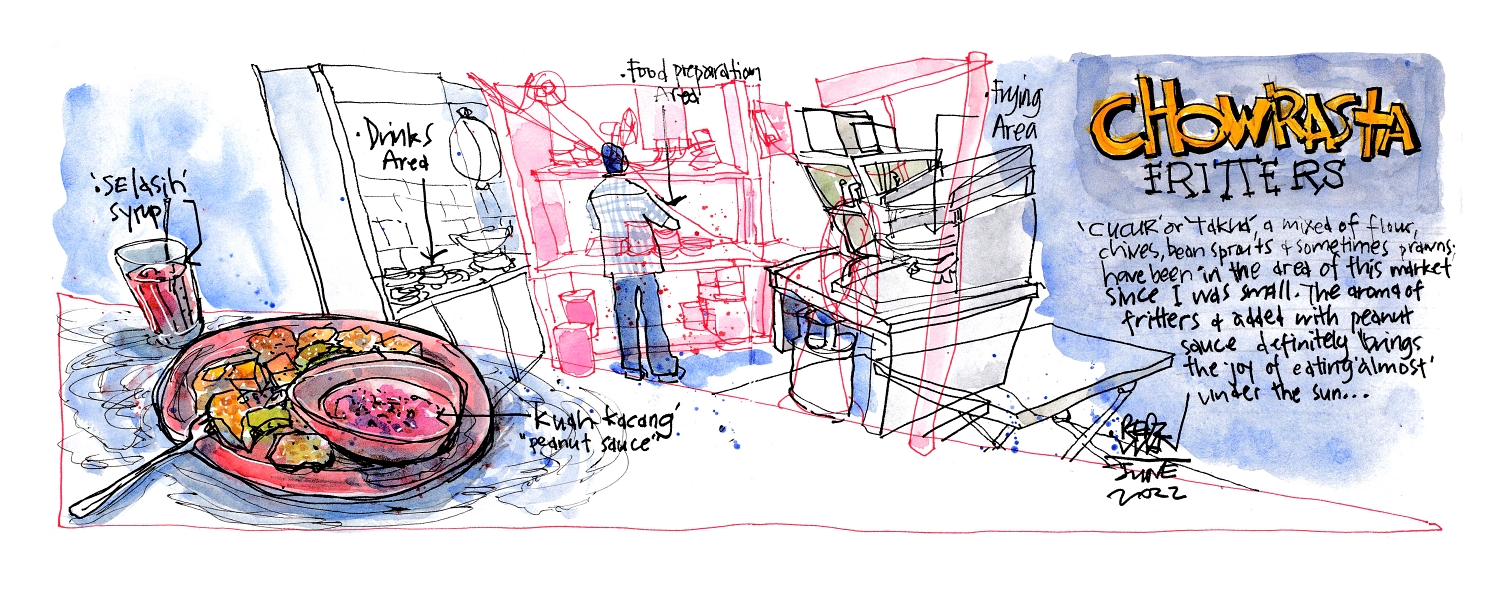

When drawing, the act becomes a process of translation rather than reproduction. The sketcher does not simply reproduce form but interprets it. A single stroke can capture the hush of a late afternoon, the warmth of sunlight filtering through leaves, or the weight of silence in a crowded café. Through this translation, the drawing embodies a personal truth, a blend of perception and reflection. The aroma of freshly brewed coffee, the rhythm of footsteps, or the laughter of strangers completes the emotional cycle of being in a place. A good meal or familiar scent makes the environment more vivid, reinforcing how sensory experience completes the visual and emotional unity of a scene.

To draw is to articulate the silent dialogue between seeing and being. The surroundings, the activities, objects, and human presence become threads that weave together into a narrative that is both observed and felt. A sketch becomes a choreography of time, translating presence into rhythm and rhythm into meaning. The artist moves through the scene not just with the hand, but with the whole body, with awareness. Each stroke of ink or wash of watercolour is a condensation of experience into essence. A faint wash of blue might suggest fading daylight; a smear of grey might evoke humidity after rain. Through these subtle gestures, drawing becomes an act of mindfulness. It captures not only what the eyes perceive but what the body senses and the heart remembers.

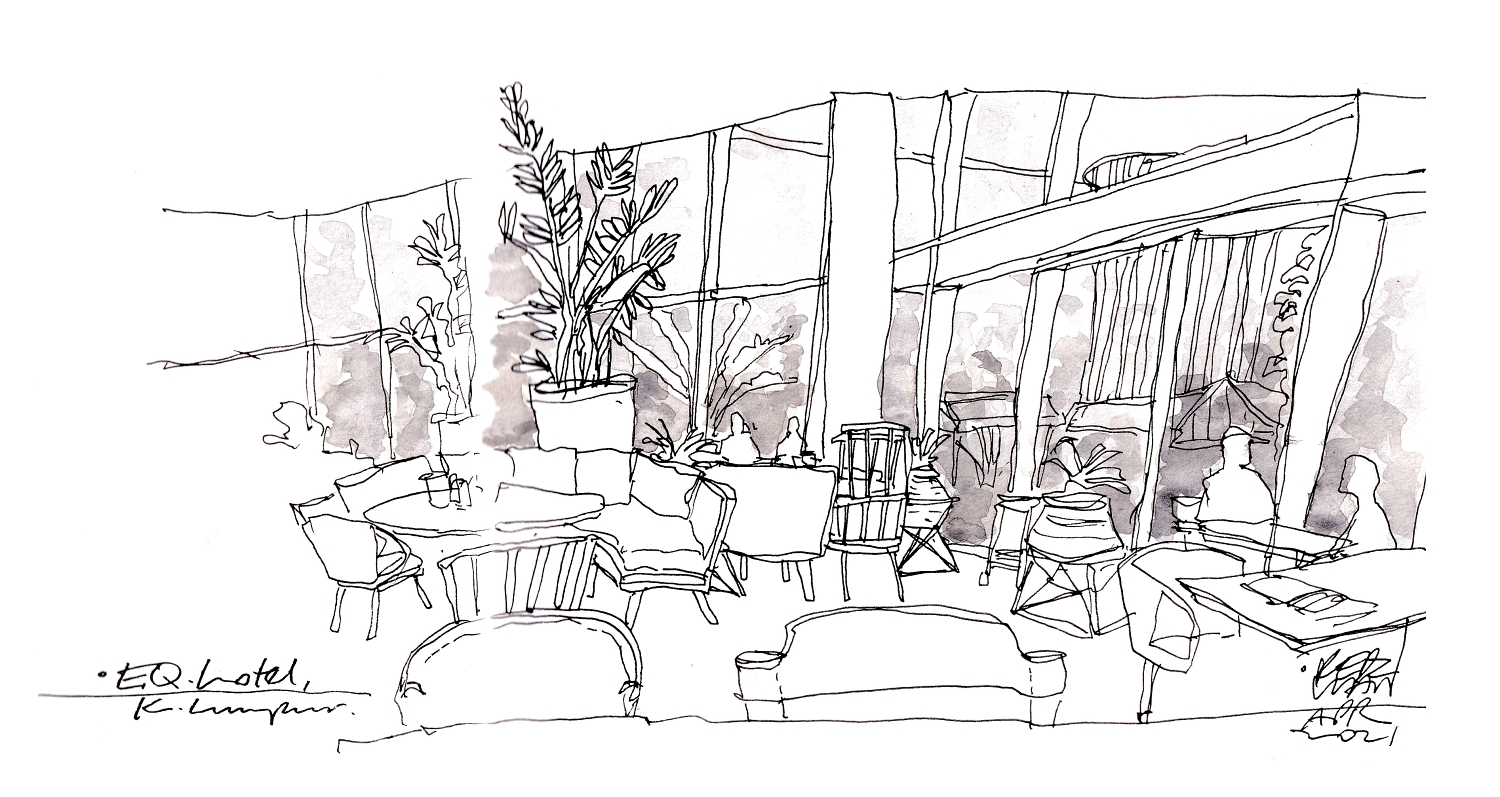

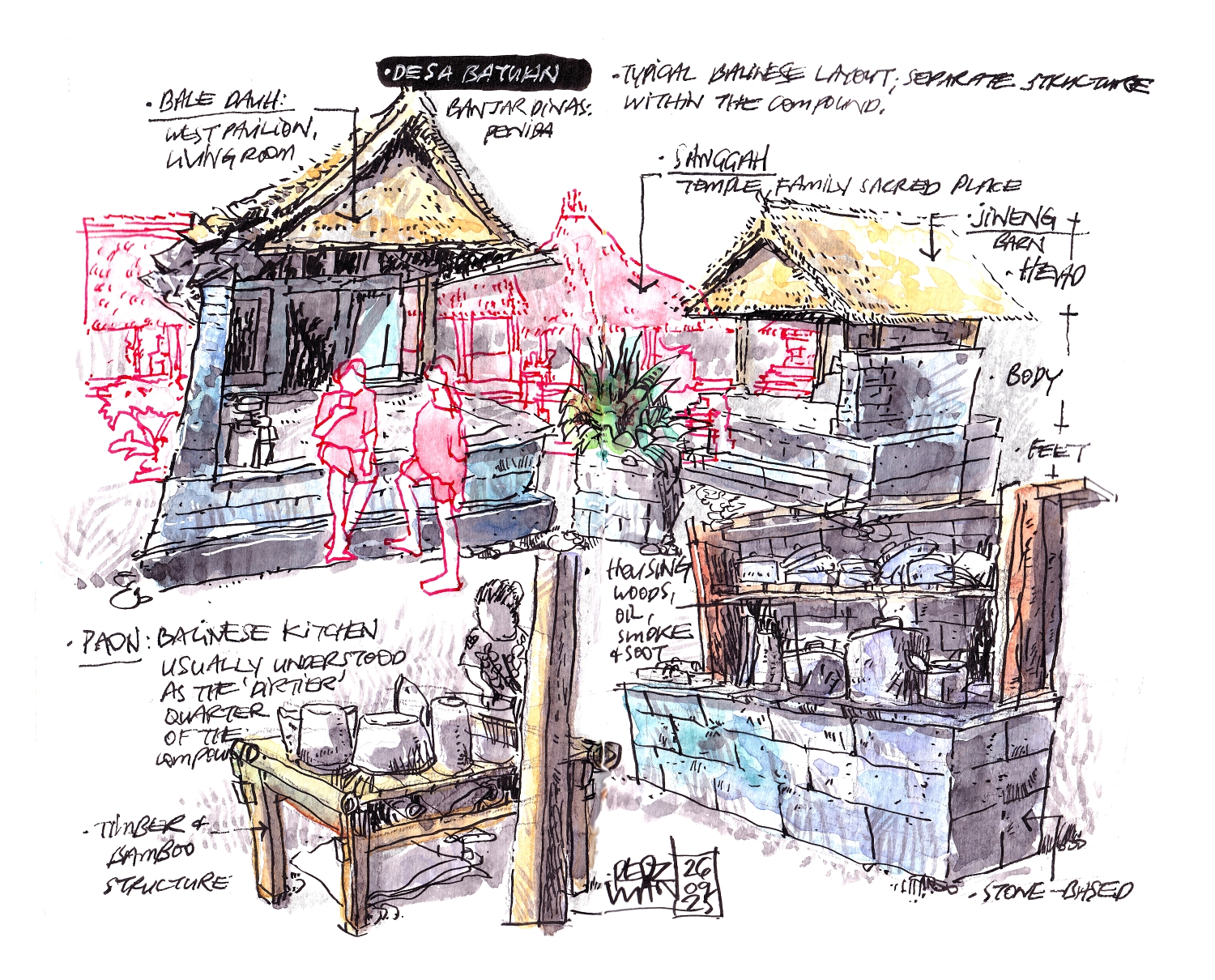

This transformation marks the shift from space to place. Space by itself is neutral, an architectural condition of form, void, and arrangement. It is structured but empty of emotional resonance. Through drawing, however, space gains meaning. Observation turns geometry into memory. The café corner where one sketches becomes a place: a remembered intersection of scent, sound, and sensation. It holds laughter, the clinking of cups, the whisper of passing conversations, and the quiet observation of light moving across walls. Place, therefore, is never static; it evolves as the drawer interprets it, shaped by personal emotion, cultural context, and memory. The marks on paper echo the pulse of a lived encounter. Each sketch becomes a fragment of one’s presence in time, a visual trace of attention.

The sensory experience of food, for example, demonstrates how taste can influence visual perception. The flavour and texture of a meal can shape how colour is chosen, the warmth of curry might translate into earthy ochres, while the freshness of tropical fruit might call for vibrant reds and yellows. To illustrate food is not merely to depict what is eaten but to evoke the feeling of the place in which it is experienced. The drawing then becomes more than an image; it becomes a sensory recollection of atmosphere, of memory embodied in pigment and paper.

The act of sketching reveals another dimension, ‘something else’, a deeper, almost meditative way of seeing. This is where drawing ceases to be a mere technique and becomes philosophy. To sketch is to slow down, to truly look, to let the world unfold gradually. Patterns emerge, the way shadows bend around corners, how people linger near doorways, how objects align in quiet order. These small revelations become a kind of visual meditation. Drawing demands patience, attention, and a particular honesty; it insists on being fully present. It is not accuracy that matters, but awareness. The sketch becomes a sincere response to life as it happens, an acknowledgment of temporality.

In this way, sketching aligns with the practices of urban sketching, reportage illustration, and visual journaling. These disciplines share the same pursuit: to understand and simplify the world through drawings. Words and visuals often converge, forming a complete narrative. A few written notes can record the temperature of a moment, the laughter of children, or the smell of wet pavement. The drawing captures structure, geometry, and mood. Together, text and line merge into a unified expression, a visual poem of observation and memory. The sketch becomes not just an image but a document of lived experience, a dialogue between the seen and the felt.

The beauty of drawing lies in how it bridges the external and the internal. It connects the tangible world of architecture, streets, and landscapes with the intangible world of feeling, reflection, and memory. Through drawing, one learns that space is what we encounter; place is what we inhabit; and something else is what lingers within us, the residue of experience that remains after the sketch is complete. This “something else” is memory’s poetry, the quiet aftertaste of presence. It is the way the mind continues to wander through what the hand has already drawn.

Drawing, then, becomes a form of reflection, a visual meditation on existence. Each sketch records not only a scene but also the state of mind of the person observing it. The marks reveal the tempo of thought, the rhythm of emotion. A loose, flowing line may suggest calm and openness, while a dense, repetitive stroke may convey contemplation or unease. These variations show that drawing is not merely a product of observation but an extension of the self. It becomes an act of empathy, an attempt to understand the world by engaging with it deeply.

In essence, to draw is to see twice: once through the eyes, and again through the memory of the hand. It is through this dual seeing that ordinary moments become extraordinary. A sketch preserves not only the physical form of a place but also its emotional temperature, the way it felt to be there. The artist becomes both witness and participant, both observer and storyteller.

Ultimately, place, space, and something else exist in constant dialogue. Space gives the structure; place gives the soul; and something else gives the lingering echo of experience. Together, they form the foundation of a visual narrative that extends beyond representation into meaning. Drawing becomes a way of understanding, a language of seeing that unites perception, emotion, and imagination. Long after the sketch is complete, what remains is not just the image on paper but the quiet resonance of the moment itself, the breath of memory, suspended between line and silence.