AM

Could you introduce yourself and tell us about your motivation for starting Bike Commute Malaysia (BCMY)?

JL

My name is Justin Lee. I’m the director of Bike Commute Malaysia (BCMY). I was motivated to start BCMY because I was concerned about the fact that private cars are one of the highest sources of carbon emissions in Malaysia and that we need a shift in the way we move around in cities to address the climate crisis. I looked back at a generation ago when bicycles were a common and clean mode of transportation, even in tropical Kuala Lumpur. However, today, we have become highly dependent on cars, largely because of how our cities are designed with spread-out neighbourhoods that lack safe facilities for pedestrians and emerging highways that create physical barriers that increasingly disconnect communities.

Despite the challenges, there are numerous opportunities for a sustainable shift in urban design and transportation. But we do need to start somewhere, and it requires all of us to be involved. Cities like Amsterdam, which initially prioritised cars in the 1970s, have successfully transitioned to being more pedestrian-friendly and cycling-oriented through strong grassroots advocacy.

BCMY started on social media during the pandemic, where I wanted to share knowledge about how I commute by bicycle. Nowadays, when we think about cycling in Malaysia, sports and recreational cycling are the most noticeable. I saw a need for more examples and stories of how ordinary people could use bicycles as a means of ‘getting things done.’ I wanted to demonstrate that cycling short distances to nearby grocery stores and shops is feasible, and if the train station is within cycling distance, you can go even further with this combination, thus making a car-lite lifestyle in the Klang Valley more feasible.

However, if safe infrastructure for active transportation, such as walking and cycling, is not available, it does not become a feasible or attractive mode of transportation for the larger demographic here. BCMY has also highlighted the importance of people-centric urbanism and the need to shift our priorities away from car-centric approaches. While looking at Western solutions can be helpful, it is more important for us to imagine how we can transform our streets within our unique context of Malaysia.

As architects, we have used visual advocacy methods through initiatives like Reimagining Streets, where we focus on the Malaysian context and create photomontages to illustrate the possibility of safer, more sustainable environments through before-and-after comparisons. Given that wide roads for cars take up significant space, we can reconfigure streets to prioritise people and vegetation, which helps cool our urban environment while supporting sustainable active transportation. Reimagining Streets translates theory into tangible, contextual ideas that the public and policymakers can visualise while also shifting their perspectives on streets.

AM

BCMY has recently established itself as an NGO. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

JL

In 2023, we registered ourselves as an NGO to establish a stronger presence and broaden our opportunities and capabilities. We were keen not only on raising awareness on screen or paper but also on learning how to initiate physical change on the ground. For this, being proactive and engaging with various stakeholders from different sectors was required to initiate meaningful change.

BCMY, which initially started as a bicycle commuting advocacy group, now has a stronger focus on advocating for the transformation of urban streets to make them safer. We believe that improving infrastructure is essential before we can expect a larger demographic to be encouraged to adopt active transportation.

From a public health standpoint, approximately 6,540 people die from road crashes annually in Malaysia, which translates to an alarming average of 18 fatalities per day, with speeding being the primary factor. Quite often, people highlight the need for better enforcement and education to curb behaviours. While this is important, the design of streets plays a crucial role in self-enforcing safer vehicle behaviours. By implementing thoughtful designs, we can create safer roads for all users, including pedestrians, cyclists, people with disabilities, and motorists. Safer streets can also address a variety of complex issues, including reducing carbon emissions, improving public health, enhancing first and last-mile connectivity, ensuring universal accessibility, and supporting public transportation.

AM

I think we can move on to discussing the projects you are currently working on. The SK Danau Kota 2 Safer School Streets project has gained significant traction on social media. Could you share more details about this project with us?

JL

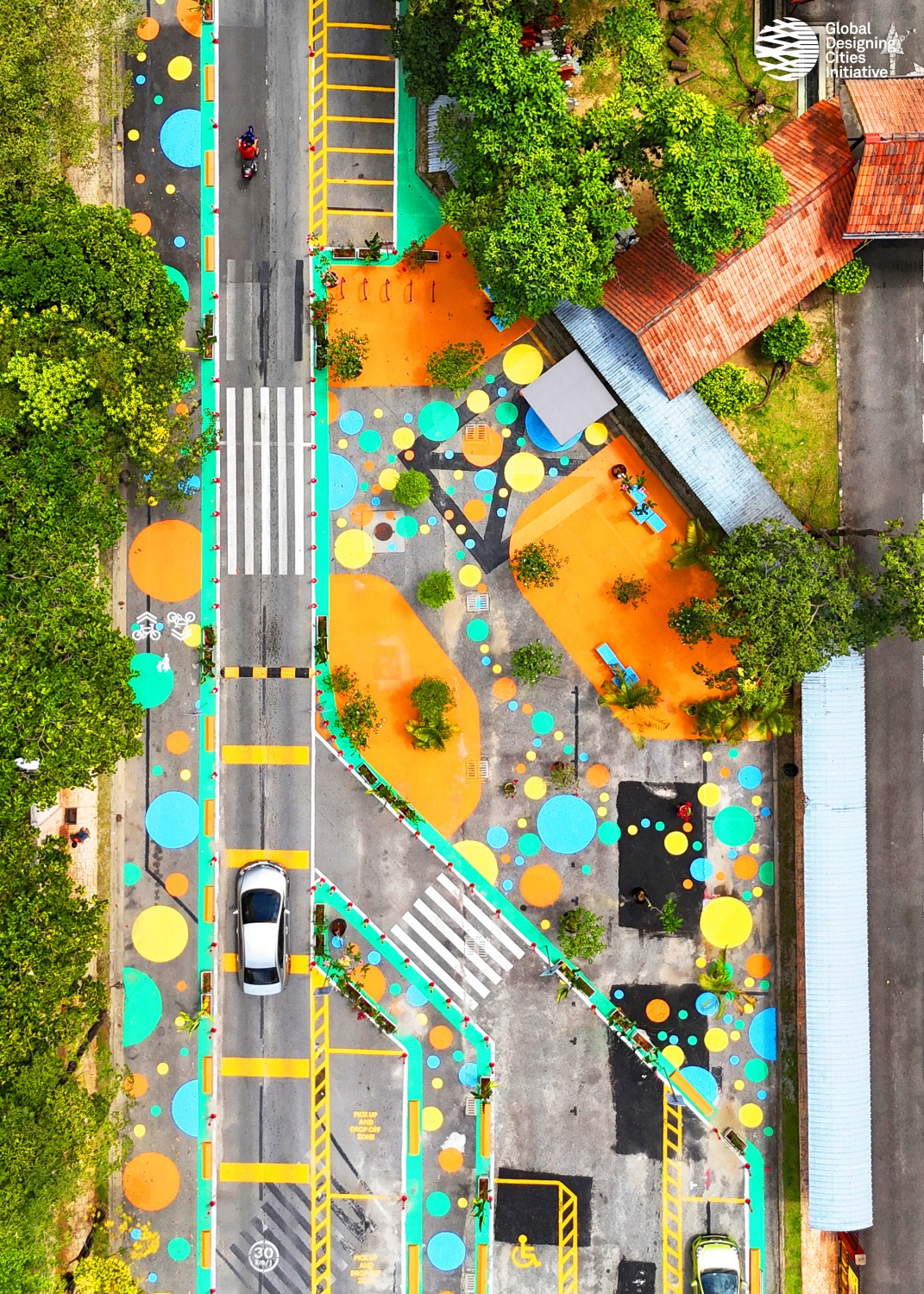

The SK Danau Kota 2 Safer Streets project primarily aims tocreate safer school streets as a basic need for children while also supporting the 30 km/h speed limit around school zones. This ongoing project by Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL), supported by the Global Designing Cities Initiative (GDCI), involves Bike Commute Malaysia (BCMY) as the local liaison. The initiative, part of the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS), includes consulting with the school and testing new street design approaches in the area.

Data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia reveals that traffic crashes are the leading cause of death for children under 14 in Malaysia, with high speeds identified as the highest risk factor for fatalities on the streets. Despite 30-kilometre-per-hour speed limit signs in school zones, many vehicles exceed this limit, posing risks to pedestrians, especially students. SK Danau Kota 2 school was no different. Before the intervention, vehicles tended to go fast and there were incidents of near misses reported when children were crossing the street.

The SK Danau Kota 2 street was made safer by adding traffic calming measures, including lane narrowing, speed bumps, and reducing the turning radius at intersections, which have been successful in lowering vehicular speeds to below the 30 km/h school speed limit. While the narrowing of vehicle lanes heightens the sense of awareness for drivers, the reorganisation of space also meant more space for pedestrians away from traffic. The site sees up to 57% increase in pedestrian space. That is 1356 sqm of asphalt space reclaimed. A new shared andprotected cycling and pedestrian path was added.

Pedestrian crossing distances were reduced by 70%, from 10.5 metres to 3.3 metres, thereby minimising the time pedestrians are exposed to traffic risks. Additionally, the redesign has removed the danger of vehicles moving directly at the school gate entrance where children gather. This space was reclaimed for a waiting plaza. This redesign also addresses issues of illegal parking and clutter from cars that previously obstructed visibility and safety.

The interim phase of the project utilises semi-permanent materials that could be implemented at a low cost. Flexible poles, concrete curbs and planters were used to define the new outline of the new street design, while the new pedestrian spaces were uplifted with colourful patterns using paint. Street signages, such as speed humps and speed limits were added. Trees were added to the plaza to further soften the environment which was once quite harsh, and promote the need for more greens on our streets. Aside from having builders involved in the 2-week construction process, 40 volunteers from the community attended a 1-day painting session that helped complete a vast majority of the paint works for the site.

A few months after completing the project, we observed an increase in bicycle users on the new lanes and more pedestrians overall, with children now spending more time on designated facilities instead of asphalt. Vehicles are moving at safer speeds and in a more

organised manner. Interestingly, we have noticed vehicles stopping for children at pedestrian crossings, a rare sight in the Malaysian context. Moreover, the transformation demonstrates that there is room for streets to inspire curiosity and creativity in children, which is essential for their growth and development.

Through engagements with the school community, including students and teachers, we received positive feedback. Over 90% of the students felt safer and preferred the new street design. Teachers also noted a significant improvement in safety and the security guard needing less attention at this school gate minding vehicles. The intervention has contributed to vehicles travelling at safer speeds and ensuring a safer environment for all road users, especially children.

AM

Could you also summarise this project’s timeline?

JL

We started in July 2023. Initially, we selected the site and engaged with the community, including school students, parents, PIBG (parent-teacher association) members and teachers, to gather their input on street design. Following this, we conducted data collection and measured the site and street dimensions. The project design phase followed, which involved several iterations.

In October, we launched the first pop-up intervention, a temporary installation using cones, water barriers, and paint, completed within seven hours. Pop-ups serve as trials to observe how vehicles adapt to new street geometry. They are easily movable since they are not permanent fixtures. The interim project implementation was completed in January 2024 within two and a half weeks with the assistance of our contractor and volunteers. We used semi-permanent materials for this phase. Post-project completion, we conducted another round of data collection, including pedestrian and vehicle counts, speed measurements, and qualitative feedback from children and the local community. We are currently advancing to a capital construction phase. The capital construction phase involves more permanent infrastructure, such as raised crosswalks, pavements and covered walkways.

AM

JL

In recent years, concerns have grown about poor pedestrian accessibility between train stations in the Klang Valley and nearby key points of interest. Phileo Damansara MRT serves many office workers and residents in Seksyen 16. Adjacent to the high-speed SPRINT Highway, pedestrians face unsafe conditions due to a lack of safe walking facilities.

The Phileo Damansara MRT First & Last Mile Advocacy is an independent Bike Commute Malaysia Project and a collaborative effort with the Petaling Jaya Member of Parliament, YB Lee Chean Chung. In a previous newspaper article,

he advocated for the improvement of first and last-mile connectivity. In alignment with his ideas, street design solutions were proposed for the Phileo Damansara site.

The Phileo Damansara Advocacy project aimed to enhance street safety and improve pedestrian access. We created photomontages, plans, and sections to communicate what is possible to improve pedestrian access at this site and enable safer vehicular speeds. The reimagining of the street includes widening the sidewalks, adding raised pedestrian crossings, and adding vegetation and plants. In the images, we have also shown how some dimly lit places and unsafe parts of the site can be improved with lighting and even CCTV. We had even added signages in the visuals to ‘give way to pedestrians’ at crossings and some 30km/h speed limit signages.

These images along with the data were used as tools for advocacy when engaging members of the public, and other policymakers to garner support. Different stakeholders, from a technical background to laypersons can understand the designs clearly.

The design had to be data-driven to justify the intent of the project. Therefore, before any designs were made, many observations were done at the site. We collected hard data by being on the ground and counting pedestrian and vehicle numbers. We collected vehicle speeds and also performed qualitative interviews with the walking and cycling commuters who highlighted the challenges they face due to inadequate facilities.

Working closely with YB Lee, we secured an audience with the mayor who had visited the site with relevant departments from the city council to coordinate and initiate on-site implementation.

It is important to clarify that the ‘Reimagining Streets’ photomontages were tools of advocacy to change the way people think about a certain street and to get buy-in for the project. As the project is currently advancing to the implementation stage, the images should only be used as a reference and should not reflect the outcome of the built project, as the project is subjected to feasibility, budget considerations and the complexities of stakeholder and government processes. Nonetheless, this project marks a significant step forward. It illustrates the process of bottom-up advocacy through engagements and collaborations with policymakers, local councils, and stake-holders. We have high hopes that the project will be implemented to the best possible quality, if not in the coming phase, then in the future phases.

AM

Could you provide an overview timeline for this project? This will help readers understand the steps involved in such an advocacy project.

JL

Before any design is made, decisions made need to be data-driven. The project started with data collection on-site during peak hours in the morning. We observed how many people were walking in an hour, and we found that it was around 856 people. In contrast, there were approximately 1271 vehicles nearby. 40% of users of the street were pedestrians, however, the lack of adequate pedestrian facilities highlighted the disparity in space allocation between pedestrians and vehicles.

Based on the data, we then analysed the site and its existing geometry and proposed street improvements, such as widening the sidewalk and adding vegetation. We had a walkabout on-site with YB Lee and met at their office to discuss and present our proposal. We shared data regarding the site to justify the importance of having safer street designs.

Additionally, YB Lee organised a walkabout with the MBPJ mayor and all relevant stakeholders at the site to further advance the project’s progress and influence its implementation. This is a very organic process where gaining trust, building relationships, and collaborating with stakeholders is crucial for achieving a larger impact. It often builds upon previous interactions and involves developing trust over time.

AM

I’m sure you’ve faced numerous challenges while managing these two projects. Could you share one or two of the most memorable difficulties you’ve encountered while running Bike Commute so far?

JL

As communities and governments aspire to create low-carbon, safer, and more equitable cities, the reality of achieving these goals is not always straightforward. This is especially evident given our heavy reliance on cars. Any resistance to the experience of driving such as speed reduction, let alone claiming lanes and reorganising streets for greener transportation are often met with pushback.

Our process of working on streets requires engagements and collaborations with a diverse range of stakeholders, including the government sector, private sector and members of the public. We are often quite strategic with our engagements and have to be creative to create buy-in from them. Every community is different and being adaptive is also important. This complexity distinguishes street design from architecture. While architecture typically involves designing a single building within defined boundaries to satisfy a client, street design must address the needs of numerous street stakeholders. This makes the process both challenging and incredibly fascinating.

During our engagements, stakeholders are often worried that they’ll lose through a street transformation, therefore, it is important to highlight what can be gained. Congestion is usually highlighted as a concern, for example, if a street is currently congested, chances are congestion will only worsen in the coming years with more development. We can observe that, even by building more highways over the last 30 years, traffic is even worse today. As quoted by Einstein “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”. Hence, we emphasise safer streets are a longer-term solution by promoting multimodal transportation. That means streets that offer more transportation options that are more efficient than just car-oriented streets. Active Transport and public transport like cycling and buses, take up less space on the road while moving more people. This is a longer-term solution which also addresses traffic while creating an age-friendly and people-centric community.

For implemented projects like the SK Danau Kota Safer Streets, given the diversity and density of the neighbourhood, there were bound to be some people who were sceptical of the project and there were similar sets of concerns as described before this. Nonetheless, it was important for the project to be implemented and tested to observe the effectiveness of the design. Sometimes an idea needs to be realised or shown to be understood. (A) few months after the implementation of the project we see that traffic has become more organised, there was an increase of school children safely using the new facilities and an increase in pedestrian and cycling numbers.

Every day, we observe numerous locations across Malaysia that lack basic infrastructure, forcing pedestrians to take risks on high-speed roads. The scale of this problem is immense, and we cannot address every street alone. Therefore, we are building capacity and conducting workshops with street engineers to amplify their impact to improve street design. Additionally, we are looking to address systemic issues by reviewing and synergising our standard street design guidelines and providing recommendations to influence broader changes.

AM

JL

Streets are the city’s largest network of public spaces, acting as essential channels for movement and transportation. Architects, traditionally focused on individual buildings, should also consider the spaces between buildings as more work and creative solutions are required in this space. Streets are integral to the user experience and Architects possess valuable skills and sensibilities that can potentially contribute to better streets through advocacy and utilising their visual skills that may not be as common in other professions.

While our primary motivation behind our work is to save lives through safer street design, this initiative also addresses several complex and existential challenges, including climate change and an ageing society. We hope to scale up these initiatives and gain broader support from decision-makers and the public. Ensuring road safety for children is a fundamental need—every child deserves to travel to school safely. When schools are safer for children, they become safer for all users on the streets—people of varying physical abilities and ages. Our goal is to raise awareness and achieve universal acceptance of these improvements.

As a grassroots movement, there is a role to play in filling the gaps in governance. While sometimes, it is important to be critical of what is lacking in our cities, it is also important to be constructive and understand what challenges our policymakers and authorities face. We need to be able to learn to work collaboratively and support them in the process of change.

Our work sits at the crossroads of design, policy change and advocacy, which is an uncommon but exciting position for an architect to be in and bring about meaningful change. Malaysia needs more architects engaged in these efforts to advocate for better urban environments.

I hope more architects will find interest in this cause because our cities require

more comprehensive advocacy and action.