DATUM:KL 2024 DAY 1

REPORTED BY AR. EDRIC CHOO

DATUM 2024 started with a warm welcome from KLAF Director Ar. Dr Lim Teng Ngiom. Dr Ngiom introduced this year’s theme, “Space, Time, and Meaning,” emphasising the chosen topics’ significance. He referenced a recent speech by Prime Minister, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, stressing the importance of reflecting on our cultural values and diversity amidst the rapid advancements in various fields, including the recent developments in Artificial Intelligence.

Following Dr Ngiom’s remarks, PAM President, Adjunct Professor Ar. Adrianta Aziz, extended a heartfelt welcome to all attendees. He highlighted DATUM’s longstanding tradition of gathering international speakers and attracting over 2000 participants annually from diverse fields within the built environment. He encouraged attendees to seize the opportunity to engage with industry leaders, enrich their knowledge, and foster collaborations in architectural design.

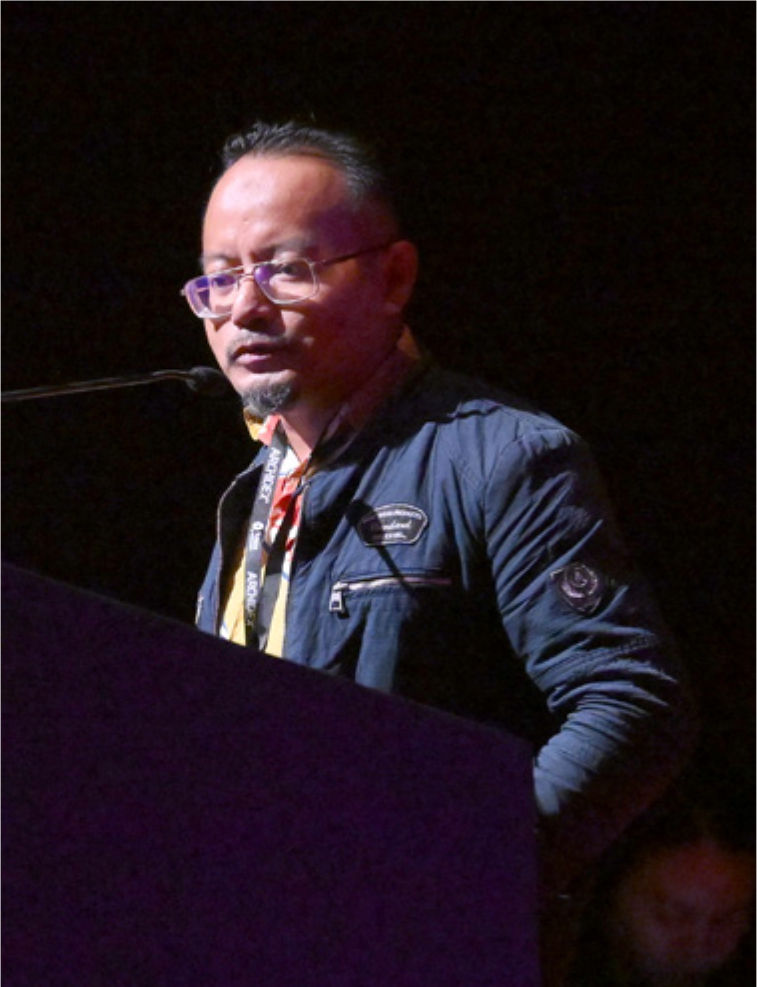

Datuk Ar. Azman Mat Hashim, President of LAM, then took the stage, commending the newly appointed PAM President, KLAF Director, and conference organisers for their efforts. He reaffirmed LAM’s commitment to supporting initiatives that enhance the architectural profession and elevate discourse. Stressing the importance of technological innovation in construction, he expressed optimism about its role in advancing sustainable practices.

Datuk Azman highlighted LAM’s pivotal role in advising and regulating matters related to architecture and interior design, as well as its active engagement with governmental bodies to advocate for the profession’s interests.

Concluding his address, Datuk Azman underscored DATUM’s significance as a premier platform for local and international architects to showcase their work and exchange knowledge. He expressed hope for the continued success and growth of the conference in the future.

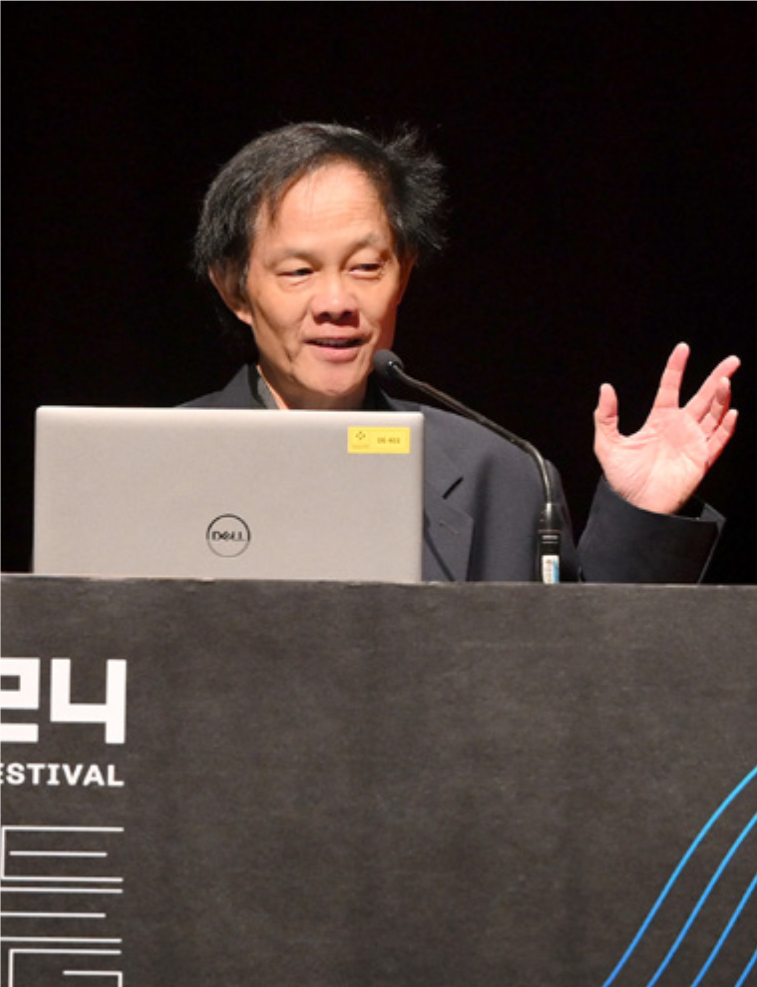

Dr Yu Kong Jian’s presentation at DATUM:KL highlights the concept of “Sponge Cities” and their significance in managing water in urban environments. He begins by reflecting on his childhood experiences in a village where natural flood management techniques were practised, contrasting them with contemporary solutions involving concrete infrastructure. He critiques the environmental and social impacts of conventional flood management strategies like concrete dams and channels, emphasising their contribution to carbon emissions and ecosystem disruption.

Dr Yu advocates for nature-based solutions inspired by traditional farming practices like terracing, which slow down water flow and promote water retention. This approach, termed “Sponge Cities,” involves integrating natural elements such as ponds, terraces, weirs, dykes, and islands into urban design to manage water sustainably. He illustrates the success of these methods through numerous projects across China, including the extensive 7,000 square-kilometre project in Guangzhou, which effectively manages water while benefiting local ecosystems.

Furthermore, Dr Yu highlights international examples like Banjakitti Park in Thailand, a flood storage sponge park created through community efforts. This park not only mitigates flooding but also fosters biodiversity and recreational spaces during dry periods.

His overarching message encourages a paradigm shift in urban planning towards sustainability and resilience. He urges the audience to embrace a mindset that values ecological balance and community resilience, urging them to “think like a god and act like a peasant” — emphasising humility and responsibility in managing natural resources.

In summary, Dr Yu Kong Jian’s vision for Sponge Cities offers a compelling alternative to traditional flood management, promoting harmony between urban development and natural ecosystems through innovative, nature-based solutions.

Dato’ Seri John Lau’s presentation reflects his journey through architecture, from his childhood memories in Sibu, Sarawak, to his professional achievements.

Here are the key points highlighted from his talk:

He began practising architecture in 1976 in Sibu, initially working on small projects. His childhood experiences visiting his old house in Sibu later in life made him realise how perceptions of space can evolve. He won his first competition-winning project in 1978 for SISCO, Kuching, based on his ‘Dinamo’ concept. The project, however, faced delays and was eventually built on a different site. He emphasises the importance of natural ventilation in his designs. Examples include his own house on a slope and a vacation house elevated for horizontal and vertical ventilation.

Lau showcased several significant projects completed in Kuala Lumpur and Sarawak. Notable examples include the Bintulu Civic Centre, where he incorporated cross ventilation and a masculine form, and the Borneo Civic Convention Centre, inspired by the tropical ‘Ririk’ tree leaf for its roof design.

For the Rimbunan Hijau project in Sibu, he drew inspiration from the swan, the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro, and the Gateway building in France. The floor plan metaphorically represented a swan wing opening towards the Rajang River, though the final construction deviated somewhat.

Lau discussed challenges such as the Sarawak History Museum project, where initial designs were not well-received by the client. Through perseverance and multiple redesigns, he eventually convinced the client and completed the project. In addition to being an architect, Lau has ventured into development and contracting, expanding his role within the industry.

Overall, Dato’ Seri John Lau’s presentation outlined a career marked by creativity, resilience in overcoming challenges, and a deep commitment to integrating environmental considerations into architectural design. His projects reflect a blend of local inspirations and global influences, contributing significantly to the architectural landscape in Malaysia.

Prasanna Morey’s approach to architecture is characterised by fearlessness and a deep exploration of the self through design. His practice, ‘Madhushala,’ which began in 2009 in Pune, India, is not just about creating buildings but about dreaming, playing, discovering, and exploring through architecture.

The philosophy behind Madhushala emphasises blending modernity with elements of the past while respecting nature and authenticity. Morey’s team experiments with architectural elements such as lines, planes, volumes, light, and texture, using authentic materials within budgetary and contextual constraints. For him, architecture isn’t merely about manipulating forms; it’s about creating meaningful spaces that serve as foundational places.

A significant aspect of Morey’s work is his homage to history and culture. He integrates modern architectural practices with traditional wisdom and values, creating spaces that resonate with a sense of place and identity. This blend of modern and historical influences is evident in projects like the P house, where he uses modular construction to create versatile spaces that maximise light and ventilation.

In another project involving a house on a slope, Morey explores terracing as a design element, focusing on interaction spaces and privacy. His designs are not just functional but also aim to enhance human experiences through thoughtful spatial planning and integration with the natural environment.

Beyond residential architecture, Morey’s portfolio includes diverse projects such as a steel pavilion inspired by fireflies, a multipurpose community hall with a curvy brick wall, and a resort that references fort design, each demonstrating his versatility and commitment to creating unique, culturally resonant spaces.

Overall, Prasanna Morey’s architectural practice embodies a holistic approach that values creativity, cultural heritage, and the symbiotic relationship between built environments and the natural world. His work reflects a constant quest for identity and self-realisation through architecture, making meaningful contributions to the built landscape of India.

Praveen Bavadekar’s approach to architecture, as showcased in his presentation, is deeply rooted in context and innovation. His firm, Thirdspace Architecture Studio, based in Belgam and Puni, India, emphasises intelligent strategies for architecture and urban design. Here are some key points from his presentation:

Bavadekar believes that architecture should respond to its surroundings. He draws parallels between his architectural approach and Hindu methodology, such as the concept of ‘in-between’ spaces and entities like Narasimha, symbolising the blending of binaries. Bavadekar demonstrates a dynamic approach to architecture, showing how his own house and office space evolved. This reflects his belief that architecture is not static but should adapt to changing needs and times.

He presented several innovative projects, such as the Hover Space in Belagavi, where a new building floats over an existing one using space frame support. Another example is the stack housing in Balagavi, which explores interlocked units for student housing and emphasises shared spaces and climatic considerations. Bavadekar explores the idea of customisable housing, where modular components allow for a variety of configurations. This approach enables individuals to tailor their living spaces to their specific needs and preferences.

In his design for a sports centre, Bavadekar integrates the building with its natural surroundings. He utilises slanted façades and angles to blend the structure into the landscape, creating an iconic yet harmonious presence.

Throughout his projects, Bavadekar employs creative use of materials, forms, and spatial arrangements. For instance, the use of colour and sectional openings in façades to enhance interior spaces and visual appeal.

Overall, Praveen Bavadekar’s presentation highlights his firm’s commitment to innovative design solutions that not only address functional needs but also enrich the built environment through thoughtful integration with context and landscape. His approach underscores the dynamic nature of architecture as a discipline that evolves and adapts to cultural, environmental, and technological changes.

Top of Form Bayejid M. Khondoker’s presentation was a compelling exploration of how architecture can engage with and reflect its context innovatively. Here’s a summary of his presentation title: Architecture: Interwoven Realities.

Khondoker emphasised that architecture must be plural and inclusive, engaging with diverse contexts and histories to create meaningful spaces. His presentation covered several projects, highlighting his approach to creating contextual and thoughtful designs.

Nandini Hotel, Dhaka:

- Focus: Art of building over traditional design.

- Features: West façade with floating wood louvres, contributing to both aesthetic appeal and functional shading.

- Approach: Integration of public space within a graveyard.

- Components: Includes open space, a mosque, and a community clinic. Emphasises community involvement in design and use.

Mosque Projects:

Dargahtala Jame Mosque, Aman Cement Mosque, and Aman Mosque (Dhaka):

- Distinctive Features: Moving away from conventional mosque typologies. Use of circular and square forms, brick layering with curved pointing, and archways scaled to human dimensions. The Aman Mosque features a square plan within a circular form, with a unique landscape approach leading to the mosque.

Bangabandhu Military Museum, Dhaka:

- Design: Three interconnected courts (foyer, internal, and cultural), tropical plazas with landscape and water features.

- Form: Intersecting curves and spheres create skylight gaps, emphasising a dynamic and fluid architectural form.

Sheikh Abdullatif Alfozan Grand Mosque Competition:

- Concept: Non-ceremonial entrance, sunken mosque with a reflective water surface, and minaret designed to dissolve into the sky. The mosque integrates cultural spaces and serves as a community hub.

Factory Project:

- Design: Four courts for ventilation, a welcoming entrance facing a park, and a façade with planter boxes allowing vegetation to grow over time. Features water features and grand stairs that also serve as activity spaces.

Khondoker concluded with a quote from Confucius: “Where a human has two lives, the second starts when he realises he has only one,” reflecting on the profound impact and responsibility of architectural practice.

The day concluded with an introduction by PAM Past President, Datuk Ar. Ezumi Harzani Ismail, who presented the UIA2024KL International Forum theme “DiverseCity,” setting the stage for a series of engaging and diverse presentations.

DATUM:KL 2024 DAY 2

REPORTED BY XING YUE CH’NG

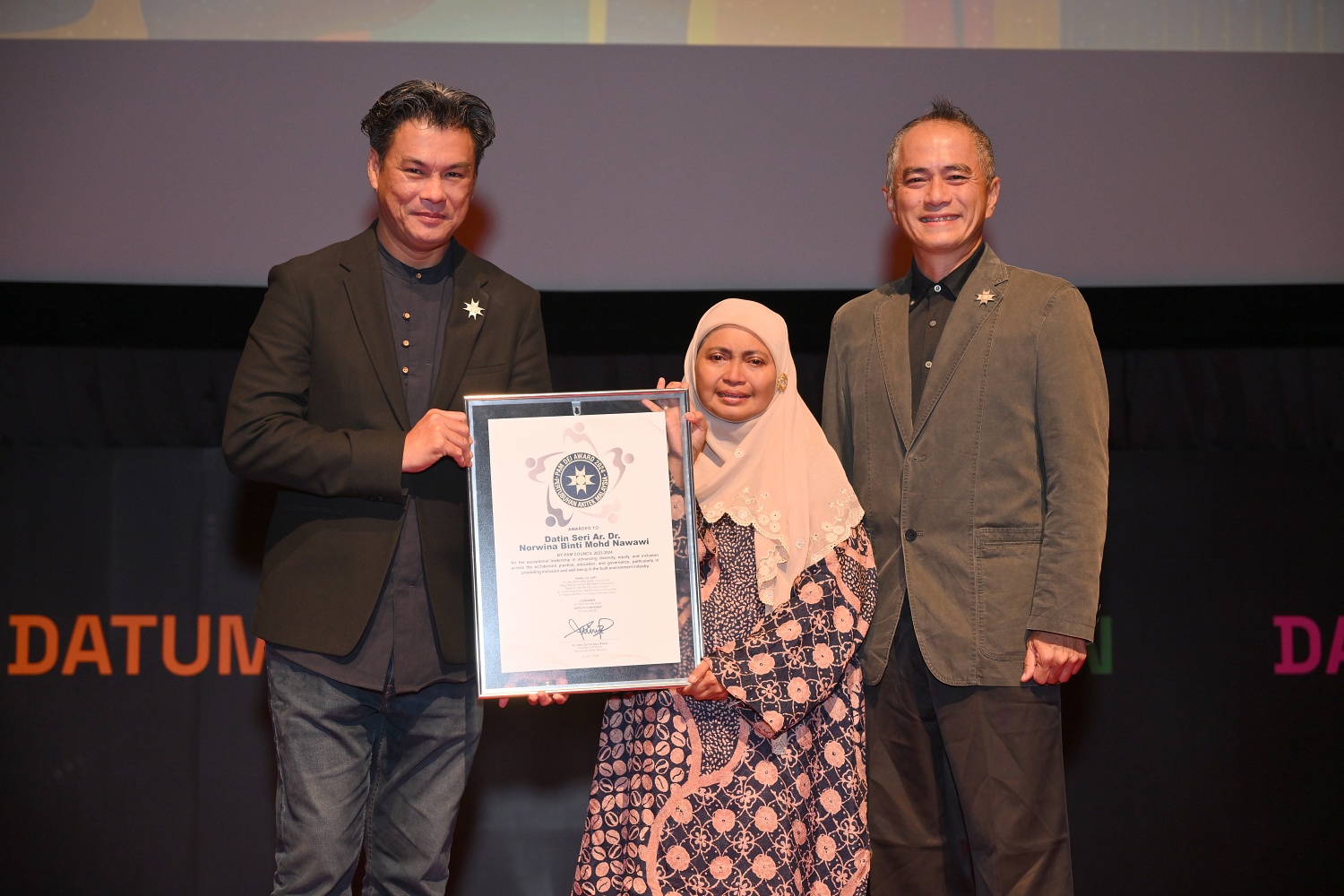

Day 2 started with the announcement that Datuk Ar. P. Kasi has been awarded the PAM Kington Loo Award 2024. This was followed by the announcement that Datin Seri Ar. Dr. Norwina Mohd Nawawi has been awarded the inaugural PAM Diversity Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Award 2024.

The 1st speaker, Wael Al-Masri’s presentation, “Hybrid Humane Architecture,” offers a compelling narrative that skilfully blends his Jerusalem heritage with contemporary architectural practice. His lived experience in the Middle East enriches his approach, allowing him to

reinterpret and integrate traditional Islamic and Arabic elements into modern projects, crafting a distinct humanistic architecture.

Al-Masri’s emphasis on the human scae and cultural context resonates deeply, advocating for designs that harmonise with their historical settings and embody the spirit of their place. His vision of merging tradition with modernity is thoughtfully articulated, illustrating a balanced dialogue between past and present — one he termed “hybrid identity”. The presentation showcases Al-Masri’s commitment to creating architecture that is not only functional but also culturally and contextually meaningful.

The following speaker, Chen Xi of Atelier Xi, presented “Architectural Improvisation, Everyday Life,” exploring how architecture as space can create unique moments in time. His insight is relatable to many architects, who often face the challenge of improvising within tight constraints of time and budget.

A particularly intriguing project he discussed involved integrating two starkly different building typologies (sales pavilion and kindergarten) into a single structure, requiring a design for adaptive reuse from the outset. Chen Xi’s work demonstrates how spaces can be crafted to allow people to shape and personalise their environments, highlighting the poetic potential of everyday improvisation within architectural design. His approach underscores the dynamic relationship between architecture and its users, fostering a sense of creativity and adaptability.

Kun Lim of Kun Lim Architect continued the engaging series with his presentation titled “Creating Connection, Creating Community,” with a nostalgic reflection on his childhood life by the river. Inspired by the river’s power, he identified circulation spines and axes as strong organising principles in his work, consistently integrating them into his projects.

Lim’s approach to large-scale master planning involves retaining existing buildings and developments and fostering connections within communities through his architectural interventions. By initially finding a simple organising design element, he gains the freedom to explore more creative design intentions.

He candidly shared moments in his career where he had to set aside his ego, acting with compassion and empathy to prioritise clients’ needs over his own desires, showcasing his commitment to meaningful and community-oriented architecture.

In the afternoon session, Jo Nagasaka, principal of Schemata Architects, brought a unique perspective with his presentation titled “Texture of the City.” His projects embody the concept of anti-architecture, where the built environment fades into the background, empowering people to design and redesign their spaces — a concept he refers to as “self-driving architecture.”

Drawing inspiration from the city’s fabric, its people, materials, and objects, Nagasaka seems to prefer designing frameworks that allow for self-operation and personalization. He advocates for the preservation of a city’s unique “texture.”

Nagasaka opposes creating boundaries between the old and the new, instead opting to retain existing elements and memories. This approach highlights his commitment to creating dynamic, people-centric environments that celebrate both history and community.

Concluding the series was Jim Caumeron from JCA, who began by highlighting the deep divide of his city in the Philippines between the marginalised communities and gated neighbourhoods.

From this context, Caumeron views architecture as a delicate balance between introversion and extroversion, addressing clients’ need for interior privacy while fostering a social connection with the outside world.

His work is characterised by its conceptual purity, standing out as vivid representations of his ideas. Preferring an ideas-based approach over a typical problem-solving one, Caumeron emphasised that while anyone can design space, it is the architect’s role to create new, unique experiences and concepts. DATUM2024 ends with great joy and happiness from all the participants and speakers. We look forward to DATUM: KL 2025.

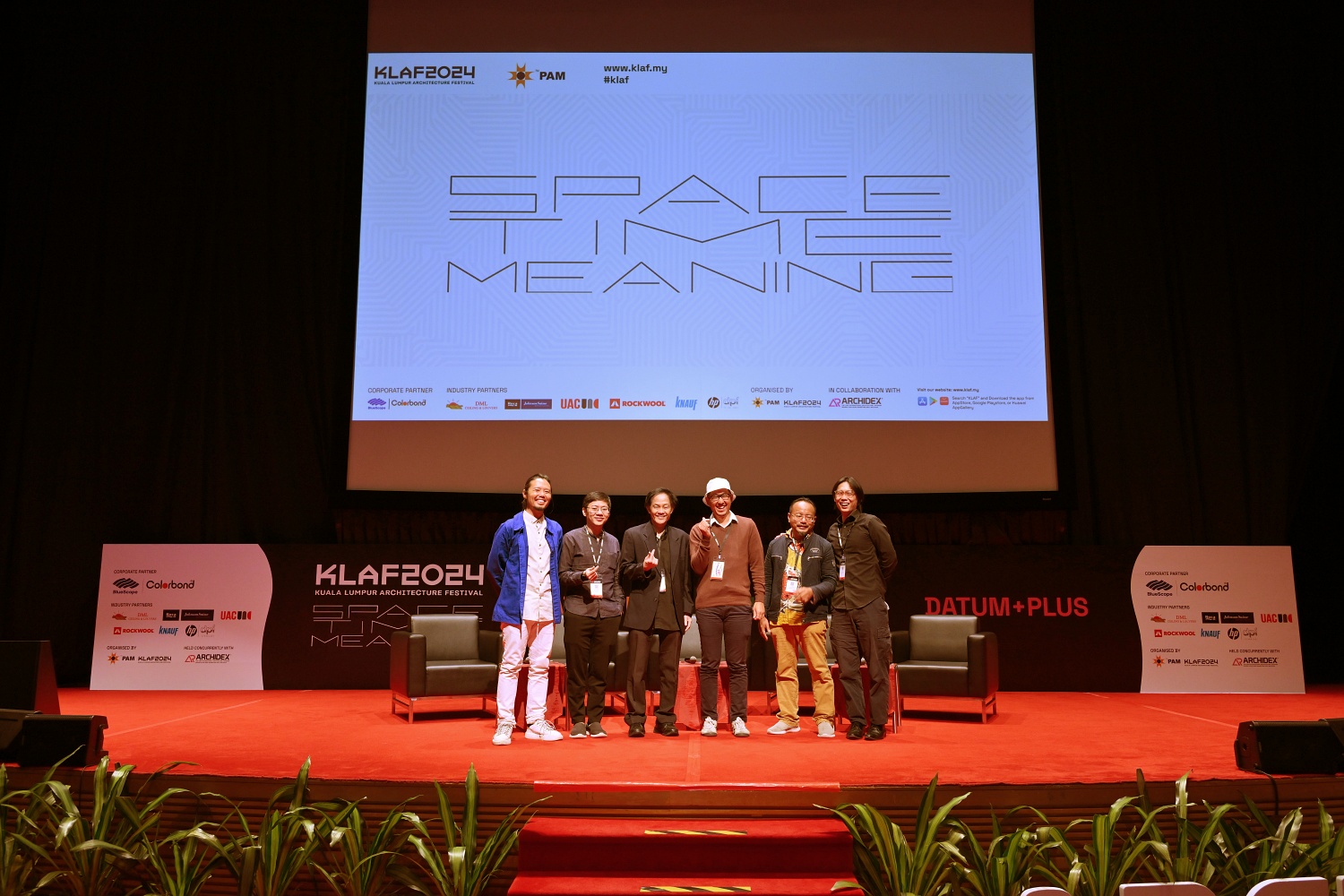

DATUM: GREEN & DATUM: +PLUS

REPORTED BY GARY YEOW

It was my great privilege to be the moderator and emcee for KLAF2024: DATUM GREEN and DATUM+PLUS. Being part of these conferences for the first time, my initial thought for all the speakers and audience was to establish the meaning of architecture across different evolutionary phases of time and space with a single question: What does architecture mean to us? As an abstract idea, architecture transcends beyond construction and building, reaching its definition and positioning, in this case, ecological architecture (DATUM GREEN) and the expansion of architects’ roles (DATUM+PLUS).

DATUM GREEN

Chatpong, from Chat Architects, started with intriguingly unusual keywords: The Bangkok Bastards. His presentation made sense of the bastardised and orphaned origins of architecture, reminiscent of Bernard Rudofsky’s “Architecture without Architects” (1964), by displaying works produced by ordinary people or unsung heroes. These buildings are sentimental in a very specific manner of respecting genius loci. They are vernacular: made out of local materials within the site proximity, illegally and dangerously built yet serving the general public. They are architecture (with a lowercase ‘a’), revealing people’s lives at the forefront, just like Chat Architects’ projects: Samsen Street Hotel, Angsila Oyster Pavilion, and RQ Bites. The buildings never intend to be the centre of attention but rather a platorm for playful elements to perform.

Speaking of unsung heroes, Lucas Loo from SEAD Build shed some light on the material we o$en see but never explore much: bamboo. His intention was clear: to shape a belief and discipline to understand bamboo better. What I found interesting about SEAD’s work is the motivation behind formulating a holistic sourcing, processing, and making of bamboo architecture from an architectural systematic perspective. Lucas highlighted the information and truth about bamboo, which are o$en overlooked when we tend to associate architecture with building forms, forgetting about material research or properties.

The same goes for Azman’s narrative on the idea of genius loci and the sense of place. Starting with an opening note on igloos (and a forest with melancholic background music), the concept was apparent, reminding me of the book “Prisoners of Geography” by Tim Marshall, in investigating building material, resources, climate, and geography from an architectural approach. “Malaysia’s hot and humid weather is the sense of our place,” Azman mentioned before presenting his work, Anjung Kelana. I had a chance to visit his house a few years ago, where some might find the massive curved timber wall an iconic statement, while I thought it was an ‘assignment’ and testament to the local timber. (It would be interesting to imagine Azman asking the timber what it would like to be, and the wooden planks might reply and wish to be fluid like concrete.)

DATUM GREEN ended with a witty presentation by Mior from Bunga Design Atelier, humbly evoking the dilemma of being a designer in fulfilling clients’ dreams of a ‘cheap, good quality, fast’ project.

It was my great privilege to be the moderator and emcee for KLAF2024: DATUM GREEN and DATUM+PLUS. Being part of these conferences for the first time, my initial thought for all the speakers and audience was to establish the meaning of architecture across different evolutionary phases of time and space with a single question: What does architecture mean to us? As an abstract idea, architecture transcends beyond construction and building, reaching its definition and positioning, in this case, ecological architecture (DATUM GREEN) and the expansion of architects’ roles (DATUM+PLUS).

DATUM GREEN

Chatpong, from Chat Architects, started with intriguingly unusual keywords: The Bangkok Bastards. His presentation made sense of the bastardised and orphaned origins of architecture, reminiscent of Bernard Rudofsky’s “Architecture without Architects” (1964), by displaying works produced by ordinary people or unsung heroes. These buildings are sentimental in a very specific manner of respecting genius loci. They are vernacular: made out of local materials within the site proximity, illegally and dangerously built yet serving the general public. They are architecture (with a lowercase ‘a’), revealing people’s lives at the forefront, just like Chat Architects’ projects: Samsen Street Hotel, Angsila Oyster Pavilion, and RQ Bites. The buildings never intend to be the centre of attention but rather a platorm for playful elements to perform.

Speaking of unsung heroes, Lucas Loo from SEAD Build shed some light on the material we o$en see but never explore much: bamboo. His intention was clear: to shape a belief and discipline to understand bamboo better. What I found interesting about SEAD’s work is the motivation behind formulating a holistic sourcing, processing, and making of bamboo architecture from an architectural systematic perspective. Lucas highlighted the information and truth about bamboo, which are o$en overlooked when we tend to associate architecture with building forms, forgetting about material research or properties.

The same goes for Azman’s narrative on the idea of genius loci and the sense of place. Starting with an opening note on igloos (and a forest with melancholic background music), the concept was apparent, reminding me of the book “Prisoners of Geography” by Tim Marshall, in investigating building material, resources, climate, and geography from an architectural approach. “Malaysia’s hot and humid weather is the sense of our place,” Azman mentioned before presenting his work, Anjung Kelana. I had a chance to visit his house a few years ago, where some might find the massive curved timber wall an iconic statement, while I thought it was an ‘assignment’ and testament to the local timber. (It would be interesting to imagine Azman asking the timber what it would like to be, and the wooden planks might reply and wish to be fluid like concrete.)

DATUM GREEN ended with a witty presentation by Mior from Bunga Design Atelier, humbly evoking the dilemma of being a designer in fulfilling clients’ dreams of a ‘cheap, good quality, fast’ project.

Mior’s take was to simplify the psychological needs and demands of what we want, starting from an attitude of frugality. It is truly inspiring when clients and designers can be quite helpless sometimes in the face of rising construction, labour, or material costs. Taking a step back to review what we want in life, reflected in our projects, is simply effortless and innovative. The elements to put up a ‘cheap, good quality, fast’ project are no longer an unreachable or over-expected ideal but a finer sense of awareness of our surroundings and existing resources.

DATUM +PLUS

I was lucky to know Realrich during the COVID-19 lockdown period, had a chance to interview him, and later visited his places, Guha and Omah Library. His mind is clear as he talked through his presentation slides, humanising architecture with images of cra$s, the universe, tectonics, autonomy and systems—like how he would describe a building as a human being. Some might find the intensity and complexity of the projects Realrich presented—not limited to buildings but also publications—overwhelming. Yet, I find the beauty in the plurality of his perspective to see architecture as a practitioner and observer. There is no one way of looking at life, so why should we conform to a single way of building or designing? I would reserve my thoughts to see more works by Realrich Architecture Workshop, and I suppose there will hardly be a conclusion to summarise RAW’s works.

On the other hand, I find CKHO’s work very direct, straightorward, and clear. His presentation, accompanied by minimal diagrams and illustrations, established a ‘democratic’ way of conveying messages to his clients, colleagues, and audience. With challenges of odd site perimeters or listed buildings, CK presented a minimal design touch in his projects, as if attempting to achieve more by doing less. If we look closely at their works, the conservation or new architectural works are simply practical and bring joy to a land or building that was once asking for help to rejoice.

The act of injecting new life into existing buildings is not unfamiliar to Shin Tseng from Urban Agenda Design Group, with notable works like High Street Studios, REXKL, and Semua House. The effort to transform these buildings in the face of economic, social, and political pressures is commendable by offering alternative visiting spots in downtown KL. One of the slides presented by Shin was a collage of commercial buildings’ facades with ‘TO LET / SALE’ signs in KL city centre, It is indeed a sad scene to see how it affects the quality of a happy street. I hope that image or what we observe in real life can inspire us to rethink what city life should be like.

Finally, Fadzlan, also known as Pak Lan, brought the presentation into a rather personal and intimate session. Like a coffee talk from a friendly neighbour (at least for me) who does architecture and mural artworks, elaborating on

his struggles, encounters, and design process. In summary, he talks about one thing: people. That is probably why I find his sharing easy to connect with the audience, with purity in compassion and communication… and splashes of colours. “We live our lives too seriously,” said Pak Lan. I hope that short sentence gives us something to think about.

As part of KLAF2024, I am thankful to interview Shin Tseng and Pak Lan, along with Shin Chang (REXKL and Mentah Matter) and Farid (RSP Architects). Please find out more on the Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia (PAM) Facebook page for more.

Thank you to the KLAF2024 team and everyone who was part of this.