VN

LT

For me, architecture is most significant when you go beyond making ‘beautiful’ building forms, to creating spaces and environments that are uplifting and serve well the people who work, live or visit it.

I am now increasingly interested in the larger contribution of architecture to the quality of the urban realm. That’s the focus and drive behind our projects – that the buildings we create are not just iconic objects on the skyline but the spaces created and their interface with the urban environment helps to enhance our experience of our cities.

KL is world-renowned for its many record-setting towers but the overall public realm, the experience of the city at the street level, our sidewalks, parks and squares, have not caught up with the skyline. So, in every project, we try to design buildings that not just serve their function, but help enrich the experience of our city at the street level and enliven the neighbourhood. Every building can play a role in creating a more enjoyable and liveable city, with pedestrian-friendly streets and a kinder, safer and more vibrant public realm outside the building.

Today, as the world faces an impending climate crisis, sustainable design principles and calculated performance metrics now become due diligence and must be integral to every new building added to the planet.

VN

Do you think that when you are given the opportunity to create larger and iconic buildings, it will offer more power to create the lively urban realm you mentioned?

LT

It doesn’t need to be a large building – it just needs every building project along the street to do its part.

Balancing leafy shade trees with commercial frontage, more open lobbies with visibility to the street or increased building setback where possible, pedestrian lighting at frontage – simple design strategies that each building can do easily to help create safer, friendlier sidewalks for pedestrians.

We often plan buildings to allow the public to pass through the building. For example, One Sentral (built in 2006) is an office tower with a 2-storey lobby to connect the historical Brickfields neighbourhood to KL Sentral. You are encouraged to walk through the building even though you have no business there – its open lobby serves as a ‘link’ between the popular eateries along Jalan Travers and Little India to KL Sentral Station and its office and residential towers, all sitting on a huge elevated podium 3-storeys above the existing neighbourhood.

Our forthcoming Oxley Towers at Jalan Ampang will also offer an “indoor street” – allowing a sheltered walk for those working or living in the area to head to KLCC park or Friday prayers.

Not just a closed, object serving its owners, architects have the opportunity with each building to enhance the street front to make a safer, livelier and more walkable city. I believe every building, big or small, has the responsibility to contribute to the life of its neighbourhood and the city.

VN

We can jump a little bit on maybe a little bit of history? Could you tell us how your architecture journey started?

LT

In school, I enjoyed especially English, history and art classes, math and physics. I come from a simple background, no piano or ballet classes – we lived in rented houses, and I had never been on a plane till the day I set off to college. I remain grateful for the generosity and commitment to education at these private Ivy League universities in America that gave me the opportunity to study there.

The liberal arts environment was life-changing. You are required to learn about and across diverse fields and discourses outside of your area of study.

Besides my major in civil engineering and architecture, I studied literature, political and social movements, German, art history, history of classical music – when before, I couldn’t tell the difference between Bach and Beethoven. Your classmates come from diverse backgrounds. We would argue things from multiple perspectives from their different areas of focus. Now, decades later, it’s amazing to see college classmates on their diverse life paths especially the women, such as Michelle Robinson and Maria Ressa, already an activist at heart, now a Nobel Peace Prize winner, for her courageous journalism and social-political activism.

I’ve left engineering behind, but it does influence my design thinking as I believe structure can be beautiful instead of cumbersome. Where possible, the building structure can be expressed as integral to the design instead of the proverbial architects’ effort to hide or decorate the structure.

VN

LT

Before leaving for the US, I knew American degrees were not ‘recognised’ as they still are today, most unfortunately.

Before I left for Princeton, I went to check with PAM and met Mr Rajadorai who preceded our legendary Fay Cheah. As he advised, I kept all my course curriculum, drawings, papers and research materials. When I returned, I went through the extra accreditation exams needed.

The LAM Part 1&2 accreditation exam is fair and not difficult because in 6-7 years of architecture education, one should have covered similar topics as in a traditional British architecture program that we have inherited in Malaysia.

VN

LT

I am honoured to be recognised in the line of PAM Gold Medallists where only 13 have been conferred since 1988.

I returned from working in New York in 1991 and feel fortunate to have been working through the past 30 years of intensive growth in Malaysia and Kuala Lumpur. Our firm VERITAS has been privileged to mirror the intense nation-building journey through the 1990s working towards the 1998 Commonwealth Games and Vision 2020. There were many opportunities for Malaysian architects working through that intense growth period of the Mahathir era.

In our practice, my fellow director and founder of VERITAS, David Hashim takes the lead in the business and management of the practice, allowing me to focus on the design and project delivery work. The PAM Gold Medal is not just a recognition of my work but of our whole team and the projects we have delivered at VERITAS.

A large project such as the entire KLIA airport services complex in 1998 (we did everything on the airside campus except the KLIA Terminal buildings by a famous Japanese architect!) or our forthcoming 79-storey Oxley Towers, needs a big team of 10-20+ architects. The heroic lone Architect is a myth today.

Besides creative vision, the leadership and management of a team of creative people and cultivating a strong culture of learning and striving for excellence and the best solutions are vital to the success of an architect’s practice and the delivery of award-winning projects.

VN

LT

Being in a male-dominated industry has its benefits – a woman architect would more likely be remembered. Like everyone else, you must build your reputation through consistent work and be willing to speak up when needed, though traditional social norms may be less conducive in some cultures.

An architect needs to always see the big picture, given our role of serving not just the fee-paying client, but the larger responsibility for the buildings we do to serve its users, the public and ultimately, our cities and built environment.

The frequent long hours for design competitions, completing large sets of tender drawings, and replying to dozens of contractors’ daily queries pose an extra challenge to a young working mom. So, there is a continuing high fallout of talented, well-trained women architects from the working profession. This is a perpetual challenge that needs deeper changes in our legacy, socio-cultural gender-based roles. However, my bigger concern is the massive brain drain across the Straits, to the Middle East and now even to London and Beijing. We lost one of our good designers recently to Zaha Hadid’s office!

VN

LT

VN

LT

We had the opportunity to work in the early stage of building Putrajaya with its new comprehensive Urban Design Guidelines. In one RFP, where we were asked to design a building for one among 4 lots, we took the initiative to design an integrated layout for all 4 lots – simply to address the issue of the scale of the new city blocks mapped out in the masterplan and its pedestrian-friendly, Garden City aspirations.

The challenge was not just about what a single building could be, but about what each could do collectively along the central Boulevard – how buildings can be read and experienced together to address the scale of the city. As each building was far apart across a 100m wide Boulevard, we wanted the design not to draw attention to each individual building, but to achieve the overall aspirations of Putrajaya as a people and pedestrian-friendly Garden City. Within each large parcel, we created ‘indoor streets’, sheltered atriums and sunken gardens to improve the walking environment and connectivity between the cluster of Ministry buildings and its neighbours. This helps to create a more human scale at the neighbourhood level to mitigate the monumental scale of the Core Island masterplan.

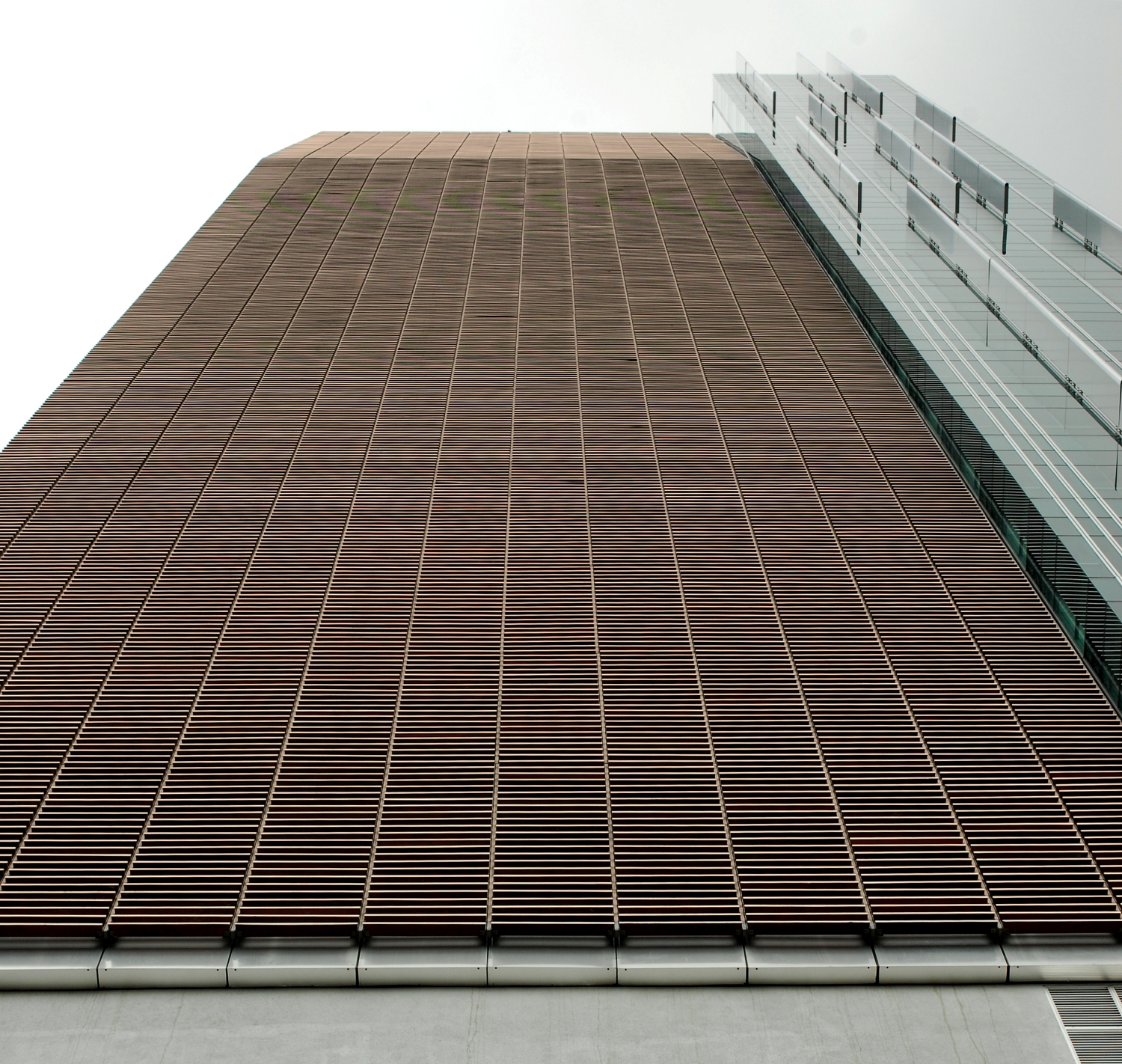

An early project in 2000, the Ministry of Natural Resources & Environment, embodies a lot of our developing design principles – where a building sees its role as a member of the street, of a larger whole, the neighbourhood. It was the first building where I started to use our local Malaysian hardwood on the external building finishes. It was also our first project where we did sun-shading studies simulation and BEI calculations, using an early software Apache. Its design and performance metrics would certainly make it a green-rated building today as it preceded the formation of Greenmark in 2005 or our Malaysian GBI green-rating in 2009. Completed in 2005, the Ministry was our earliest sustainably designed, green building – fitting for its role as the national guardian of our built and natural environment.

You often may find in a given project, a need or opportunity to question and challenge the prevailing rules or norm – it’s important to cultivate in the design process and in my team, a drive to do “best in class” – to question the norm and look for ways to innovate.

The same attitude goes into designing Digi HQ in Subang in 2006. In Digi, we created the one thing not stated in the design brief – the central sheltered, tropical atrium which turned out to be the most important, most used and remembered community space in the whole complex – a space not specified in the original brief for a new HQ with paperless and hot-desking workspace. The lasting impact is not just how the building looks like, but how the building works, and how its users live and work within. Architects try to envision how the community in that building would want to work or live, beyond providing the spaces listed on the design brief.

Then there is Sinkeh – a single shophouse adaptive reuse project that had a substantial impact on its street. We kept intact the end 19th-century shopfront to maintain the historical integrity of Malay Street in UNESCO-listed Georgetown. We re-opened the courtyard, inevitably closed up in most old shophouses. We rebuilt the deteriorated back portion in a detached steel structure to minimise impact to its adjoining neighbours, address rising damp issues and most importantly bring back daylight, views and natural ventilation into every room in the small hotel and artiste studio venue created.

The design respects and renews the traditional shophouse typology while addressing its perpetual issue of lack of daylight and natural ventilation as its occupants, traditionally multiple families and migrant workers, live in crowded tenement-like conditions with little daylight and fresh air. The building innovates with modern materials while respecting historical building typology.

For a different perspective, I must mention Saloma Link which arose from the work we did for the master plan for redevelopment of Kampung Bharu. Due largely to the complexities of traditional land-ownership in the enclave, it was very challenging to move on with our or the many masterplans that have been produced over the years including our version. With a very limited budget in hand, the client wanted to proceed with a significant aspect of the overall vision. It took just seconds for the client and the architects together, to decide that the most impactful move at the time would be to connect this historical village to its neighbour, the prospering world-renowned Kuala Lumpur City Centre – through a pedestrian bridge that was in the masterplan. Today the Saloma Link has made Kampung Bharu easily accessible to the most developed and valuable part of Kuala Lumpur with its dense urban community. The bridge has become a popular, much-visited and iconic public space attracting hundreds of visitors every day to Kampung Bharu.

More importantly, the elderly folk in Kampung Bharu take morning walks across the bridge while its young community crosses over daily to enjoy the park and facilities at KLCC in the evenings.

For me, the building project is most successful and satisfying when you see its impact on the community and its neighbourhood.

VN

LT

VN

LT

My continuing concern and one widely shared among our architects, is that Malaysian architects generally are not being credited enough for our skill levels and are not given enough opportunities to excel further. Oh! Have you seen that commemorative stamp issued for KL’s 50th birthday? (Lillian pulls out from her phone, an image of the stamp that celebrates the 50th anniversary of Kuala Lumpur.)

There are 5 buildings featured on the stamp for the 50th anniversary of Kuala Lumpur last year to commemorate the buildings in the city. As proud Malaysians, we noted that of the 5 buildings celebrated in the stamp, only the Saloma Link was designed by a Malaysian architect and built by a Malaysian contractor. For its public and community impact, the Saloma Bridge only cost a fraction of the billions of ringgits to build the other iconic buildings in Malaysia.

During my many years in the PAM Council and recent tenure as PAM President (2019-20), I initiated statistical research in our architecture industry on employment and distribution of professional fees and found large expenditures on the import of professional architects and engineering services.

Besides opening up the industry post-MCO, I spent much effort as PAM President to highlight this disparity and loss of opportunity and job creation and to urge our government to help direct more of our national and major building projects back to Malaysian professionals so that we can create more jobs, build up our companies, pay more taxes back to the nation besides very importantly, create greater job satisfaction to young professionals to help curb the extensive brain and talent drain that Malaysia is facing. The talent and wealth of experience of our Malaysian professionals need to be better appreciated and recognised. It’s an issue that has been my longtime crusade for the profession.

VN

LT

VN