To Design is to put disparate elements together in a coherent way for a particular context because there is practically nothing new to design everything that you consider to be your novel design is most likely to have already been done before in one way or another.

I think that genius is not in inventing things; but is about how you put everything together that somebody in the past had already done but you may not even be aware of.

I’m always trying to see what design means, what beauty is and where it comes from. I realised that not everybody is capable of materialising this beauty, but it seems to be most people are able to appreciate it no matter what form it takes. In my work, I try to infuse beauty into the environment that I touch. I have come to accept the platonic Theory of Forms and that material beauty on earth is a manifestation of the intangible form of beauty. This can materialise as plants, landscapes, human form, architecture etc.

SK

RHY

SK

RHY

Starting from when I was very little, I had a deep interest in nature, which meant that my entire attention had been focused on nature. I loved wild animals and the forests and still do. There were a lot of primary rainforests around when I was young, and they were a short bicycle ride away from town. So, I was always able to experience being enveloped by it.

I was never very good at studying because my interest lay elsewhere. There were always exciting things out there to relate to, why then are you trapped listening to boring lessons? I didn’t think I was stupid. In fact, I might have thought that because of most of what the teachers taught, I already more or less had an instinctive understanding. However, my interest wasn’t there. My interest was always out there in nature. I hated being confined by four walls.

My mother at one stage grew a lot of orchids and kept a lot of birds, and that was very interesting to me.

I remember when I was quite young, I created a garden in my parents’ garden, which I thought was not too bad compared to the rest of the garden.

And then, much to everyone’s surprise I got to university and read politics and economics, mainly because it was expected, and in return worked in my father’s business.

While doing that, I was developing my ability to design gardens and build houses.

By the time I got to my forties, I realised I had chosen the wrong path in life. I didn’t enjoy what I was doing, and I wasn’t contributing anything to the environment. I needed to pursue something that I was passionate about something more meaningful, something more satisfying. So, I left my job, quite penniless at the time of the Asian economic crisis. Not good timing.

When I started on the landscape, I was doing very small jobs. I was doing design and building digging things with my own hands, but I felt that there was more in line with what my life was about. I had already developed that set of skills because while I was running the business, I had bought a piece of a 10-acre land in Batu Pahat and had been working on it.

SK

RHY

Oh yes, I do! I’ve been gardening that for more than 40 years, and all the trees that I have planted there have grown enormous. The land that I have bought is by the sea, and there’s a very long line of mangroves along the coast that goes all the way to Kukup at the very tip of Johor. That is a huge nature corridor of which my land was a part.

I wanted to learn how to coexist with nature. To grow the right kinds of trees, to provide homes for birds and animals while building a garden.

I built 2 houses on my property; one has a traditional Malay typology and the other is a modern timber house that considers the tropical climate. I’m working on the garden slowly. I have planted a lot of trees for the last 30 to 40 years and am now laying out all the formal parts of the garden. I want to be able to show people that we can achieve a fairly high standard of peaceful, coexistence with nature in the garden. I have over 100 species of birds, many small mammals, reptiles and insects and amphibians that live there. This symbiosis is very important.

I go back there practically every weekend. I love waking up in the morning to the sound of birds and the sun coming up. And going to sleep with the chirp of tree frogs. Sometimes we don’t turn on the light until “senja” is over and darkness falls revealing the many stars. That is an incredible feeling. You allow the light to slowly, slowly fade until it becomes you can hardly see anything. It’s hard to describe but you could experience it. I hardly hear any human noises. Sometimes when the sea is very rough. I can hear it. It’s an incredible life.

SK

RHY

SK

RHY

SK

RHY

I would say that the show gardens are experimental in many ways. They can be very beautiful gardens, but always relatively short-lived. Sort of like an art installation. They are typically built over a ten-to-fourteen-day period, on show for a month and can receive over a million visitors over a ten-day period.

I usually design the garden up to a year in advance, but it becomes very intense over the construction period as everything has to be perfectly installed in a short time. I try to appeal deeply to the visitors, and therefore I have to understand the psychology of visitors.

I have worked in China, Japan, France, and America, amongst others, and there’s always a risk of not being able to convey the message that you intend to. Fortunately, so far, I have been able to successfully interpret the cultures that I have worked in.

I think that being Malaysian and growing up mixing with different types of people speaking many different languages and dialects is a bonus.

SK

RHY

Well yes and no.

Obviously, in different cultures, you create different types of gardens. But I think all human cultures are connected by what Carl Jung calls the collective unconscious. In my more successful gardens, I am somehow able to tap into this to create archetypal symbols that audiences can relate to.

SK

RHY

SK

RHY

To me, a lot of life is about experimentation. I am always experimenting with new things, trying new materials, engaging with new ideas, and attempting new methods. So that was a period of my life when I experimented a lot with bamboo, and another when I worked with timber, steel etc. One of my show gardens featured discarded blue jeans.

I worked with bamboo in urban projects and show gardens, and that was about learning about the qualities and characteristics of bamboo and what’s possible. I like their flexible qualities. I also like that they can be sustainably grown. However, although bamboo has been widely used in places like Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam it is not popular as a building material partly because we do not have the craftsman able to work it. So, it was all about how to bring new life to this traditional craft that seems to have been lost.

SK

RHY

I have seen gardens all over Asia and in Europe. Each country seems to have developed their own ways of building gardens. There are the great garden traditions of China and Japan. India has its mogul gardens. Indonesia has gardens that are influenced by Hindu cosmology possibly brought there by the Khmers.

In a way, Malaysia is the new kid on the block. Lacking historical monuments and the attendant landscape we can only see our historical landscape through European paintings. These paintings done mainly during the Victorian era, look somewhat like the English landscape. However, it has not revealed any real local landscape tradition.

Our country has a tropical climate which can support a large range of flora and fauna. That surely means that we have a rich raw material that we can use for developing a new typology of gardening. We can learn from the many traditions, absorb the lessons, and develop our own landscape which is unique to us.

On a more practical note, I would suggest for a start, we need to bring the forest into our cities in a controlled manner. Linking our cities and parks in an unbroken line of green to our forest reserves, and from the forest reserve to our national parks.

SK

RHY

SK

RHY

Formal education provides graduates with a sheet of paper for them to go out to get jobs. It can teach them some things, but it cannot be the end of education. Even the best students can only absorb a limited amount in the few years that they are enrolled in educational institutions.

What should be done is to produce landscape architects that can change the quality of our environment and that take an entire lifetime. This process can be shortened by good mentorship. We must remember for example that the AA was never a formal institution. That is why it is called an association.

Of course, formal education can take different forms. I wonder if you remember the days when universities offered sandwich courses where academics were sandwiched with real life.

I was very impressed with the Japanese system for non-academic professionals where they don’t teach by books. classes are conducted using images. You go to class for 6 months and you go outside and then work with a chosen contractor for 6 months. You will have to repeat a few cycles. You learn Landscape partly in class and partly by experience. The experience will round out your education.

The gardening world is so rich and full of expertise. Go to one of the great gardens in England and understudy one of the great gardens. That will put you in a good position for your future rather than, for example, trying to go for your master’s.

I’m self-taught in most things. I never got my Master’s in design and architecture until I was in my early 60s. I found that my practice was invaluable to my degree and vice versa. So, the answer I suppose is that both formal and informal education have their role, after all, education should be a lifelong pursuit.

SK

RHY

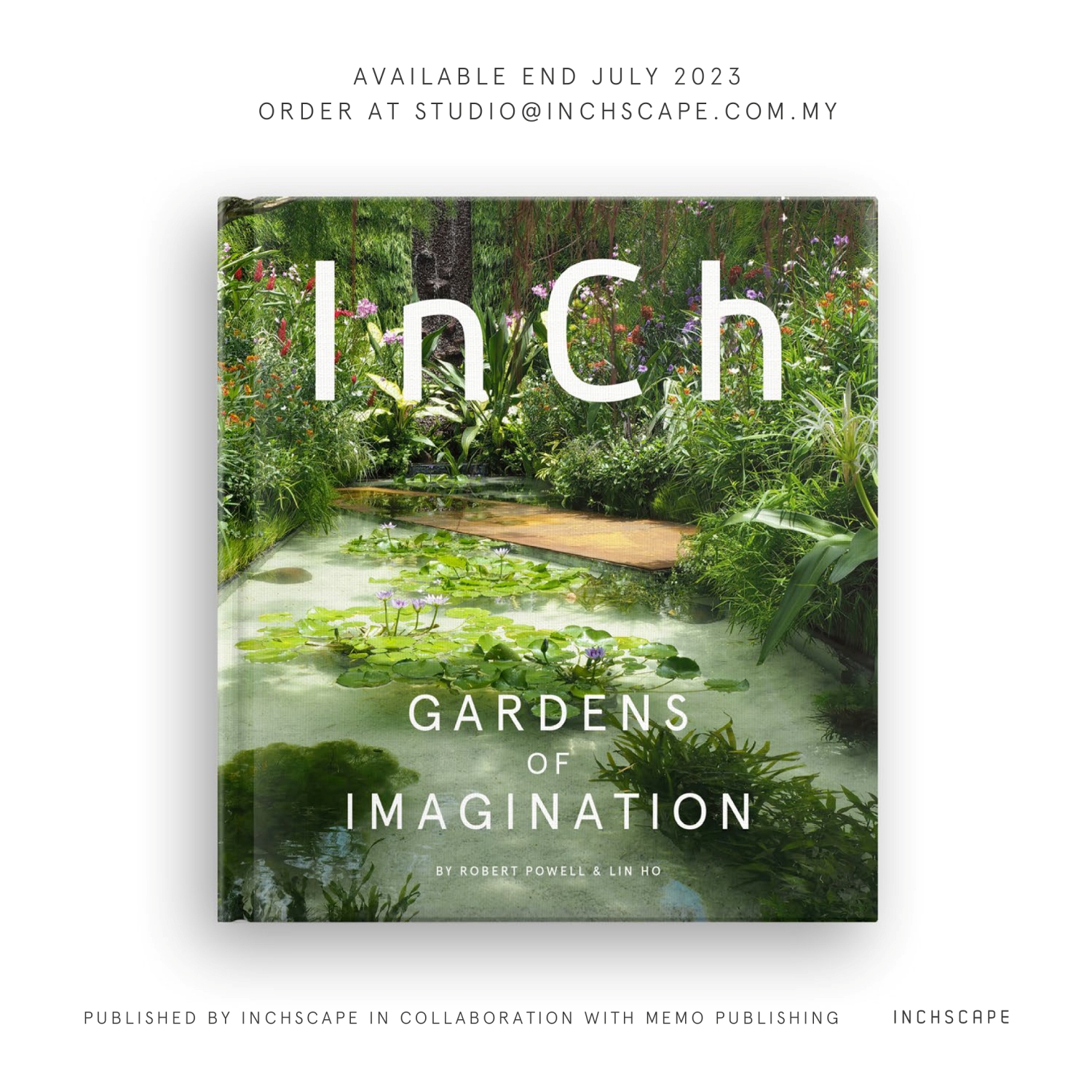

The book is called Inch: Gardens of Imagination.

I had been approached by several publishers both local and international to publish my monograph, but I decided in the end to self-publish so that I am in the position to control every aspect of the quality from design to execution.

I have been working on it for about a year collecting my past pictures finally we have a book that is bursting at its seams with a collection of gorgeous photographs of my work.

It also describes some of the philosophy and Methodology of the work and traces a history of my involvement in design.

It is written by Robert Powell who has a lot of experience in writing tropical architectural books and partly photographed by Lin Ho who is an extremely good photographer.

SK