Congratulations on winning the PAM Gold Medal! The conferment ceremony was a colourful event. In the programme for the occasion Ar. Ang Chee Cheong rendered an account of your illustrious career. Ar. Mok Chee Pann’s delivery of the citation was an intellectual discourse on your work. Members of the Jury panel have also paid personal tributes to you. Looking back at your career now, how do you feel?

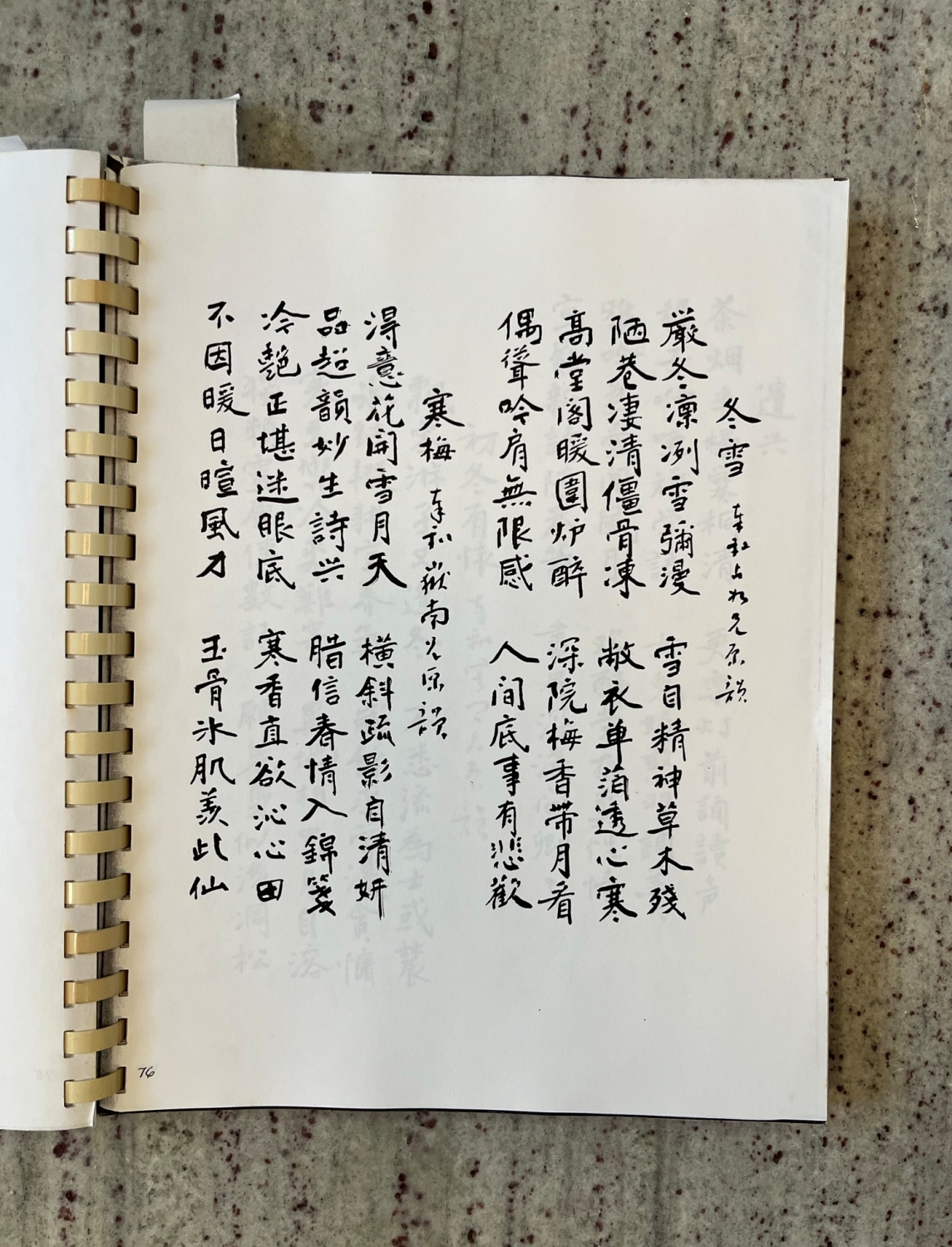

When I retired in 2000, I chose a quiet exit. I wrote a Chinese couplet. A word-to-word translation goes this way, “Honour and awards are things of the past. Away from the dust of the mundane world, the shore of enlightenment is in sight.” In truth, all through the years, I had been reticent about my thoughts on architecture and had seldom published my finished work. I had no expectations and lived a blissful life. However, when the award was bestowed upon me, I accepted it with humility and gratitude. The feeling was candid and splendid.

During my retirement, I have remained silent. I spent much of my time in the countryside. By a stream of falling water and rolling rock, I found my Garden of Bliss. Unaware of several young architects who regarded me as their mentor, I was invited to give a public lecture one day. What followed was a wave of fervency to nominate me for the PAM Gold Medal. They say, if you don’t blow your own trumpet, no one else will blow it for you. Strangely, somewhere in the well of time, someone did come along to blow the trumpet for me. It was beautiful music. Just as well that I live up to 87!

You were among the first generation of post-World War II architects. What was the architectural scenario like in those days?

When I stepped into the professional practice arena in 1966, a dozen of local architects had already set up their private practices. There was a conscious effort to depart from pre-war architectural expressions. In looking for a new direction, their buildings produced featured single roof pitches, tapered columns, cantilevered beams, precast concrete grilles to bring about that new look.

How did you place yourself in such a practice environment and how did you establish your architectural style at such an early stage?

Our country had faced a sequence of political turmoil and financial recovery was slow. It was an age of austerity. My approach to design was one of fulfilling basic needs, free of frills, form followed function, characterised by slender structure complemented by simple construction details.Step by step, I applied the theories of design as projects came my way.

I introduced vertical and horizontal planes to create a variety of living spaces, and interpenetration of spaces to relate the interior and the garden. (House for Justice Ong and two-storey house for M W Leong).

To orient the building for cross ventilation and to create a sequence of east and west wall planes taking advantage of the sun to create contrast and gradation of light. (House for K.C. Arun and Dr. Sidhu)

To develop floor layouts adapted to tropical living, e.g. Indoor gardens to bring green and nature into the interiors. (House for Rajaratnam)To raise the building’s platforms on stilts in character with the traditional houses of the indigenous people and find their relevance in modern lifestyle. (House for Major Loo and Dhamaraja)

Your design of the Hexagons and Nusantara office building exalted strong expressions of structural discipline. How did you draw up such courage to create buildings such as these?

As students of architectural studies at the Technical College, Kuala Lumpur, we studied alongside the engineering students for the subject of structure. It was with this training background that I gathered confidence in engaging structure as the resultant forms of the buildings.

The Hexagons is composed of three timber-framed hexagonal barrels suspended by steel cables anchored onto two concrete cores. The use of these three building materials and their inert strength help create and retain the form in space. The resultant beauty lies in the superb equilibrium of the structural form.

The Nusantara office block rises from the ground, spreading its columns to support the activities and the load of every floor of the 21-storey building. The cross-section of the building is a telling account of how each floor varies its width and volume of space according to its usage. The resultant structural framework enables the building to take its natural form.

We can see why these works have won awards, the projects are very bold and daring in terms of form exploration. There were fewer discussions on the Bank of Nova Scotia HQ, which won the ALCON award in 1976. The design had aluminium panels and rounded rectangle windows evoking a galactic atmosphere that would fit right into the Sci-fi movie – Blade Runner. Considering how you have only established your practice in 1966 and completed the project in 1975, could you describe how this project came about?

The representative of the Bank of Nova Scotia came to Kuala Lumpur to set up his Headquarters. He turned up in my office with a list of accommodation requirements and requested a design befitting the progressive image of his bank.

Aluminium products were new in the construction market back then. I chose to use them for the frontage and the interior details down to the air-conditioner outlet grilles. The highlight was my design of the mural made of cast aluminium. The extensive use of aluminium product design appealed to the client. I may mention, by the way, that it was the first bank in KL to have a barrier-free customer service counter.

It is interesting that before No. 8, Jalan Gurney, you have ventured into becoming a developer by developing Medan Ria, which pioneered the concept of condominium living in Malaysia. Although currently in the West, there are already similar experiments of architects venturing into real estate development, it is still quite uncommon in Malaysia. Do you mind sharing how you managed to build the project?

Throughout my practice, I made it a strategy to acquire small plots of land from time to time, designed and built, then leased or disposed of the products as a way to complement the income and expenditure of running a practice.

Medan Ria provided an opportunity to demonstrate to my clients a promising product of property investment. Indeed, an innovative product in the market requires proof of viability before the financing institutions will fund it. It was a learning process to speak the language of the bankers and win their support.

The PAM Timber House in 1977 is also another fascinating project, modelling it based on the traditional Malay Kampong House. Before this exhibition, you have already done the Hexagons, which boasts a more modern form. Is there a reason you decided to try a more traditional form for the exhibition instead?

From the very beginning of my practice, I advocated the concept of raised platform living and have built numerous houses around this concept. The principle adopted in such design was akin to the Malay kampong houses. However, I did not emulate the ornamental features of the traditional houses. This is evident in the manner in which I articulated the structural members and the interplay of lines and planes in the interior of that house that I put up for the exhibition.

It is impossible not to address climate change in our current time. Our main construction material – concrete, albeit cheap – is one of the main producers of carbon dioxide. The exhibition in 1977 was to promote the use of timber in buildings. Have you thought of incorporating timber as the main material for high rise housing instead of the common material – concrete? What do you think are the challenges if we were to replace concrete with timber as our main construction material provided that the timber is sourced from sustainable forests? Or are there any other materials that you think could replace concrete?

There has always been a contradiction concerning the use of timber in buildings. The national timber board and timber merchants were out to promote its usage in buildings. The local authorities and other approving authorities were always so strict in granting approval. Most insurance companies would slam high premiums or even reject your application.

Times have changed. Of circumstance, we should conserve timber usage. However, concrete production is also one of the sources of carbon dioxide emissions. You have asked if there is any other material that can replace concrete. Indeed, there is a need to research new building materials, especially for high rise housing. In this aspect, we should look towards China for its success in this field.

There is one passage from your previous interview where you talked about how construction activities in the 1960s were sparse and the country wanted to rebuild itself out of necessity and probably at a very fast pace. Therefore, it seemed like the zeitgeist of architectural education at the time focused on practicality and building technology. You have studied initially at the Kuala Lumpur Technical College (KLTC, now known as Universiti Teknologi Malaysia) and have also received overseas education in Auckland, you were also an active educator and was on the LAM-PAM Examination Panel. What do you think of the architectural education direction in Malaysia today and what can be improved further?

Architectural education is a broad subject. In the context of a developing nation, the first aim of an institution is to identify the manpower needs and to design a course structure in which the core subjects are to prepare students with relevant professional skills. While peripheral subjects may be integrated as a way to broaden a student’s mind, it must be born in mind that the graduate must have learnt the basic skill to be employable. Recently, I encountered a Grab delivery service guy and he identified himself as having a master degree in architecture.

Regarding your acceptance speech, you brought to notice the rampant disregard of our private and public buildings – that many of our buildings of merit have been neglected, altered and disfigured beyond recognition. Did you identify the root cause as our society being insensitive to things of beauty, art, culture and history?

Enforcing laws to preserve and protect buildings from abusive changes have limited consequences. We must cultivate the sense of aesthetics in people, young and old by adopting a long term plan of introducing aesthetic education in schools. With trained eyes, people of all levels will learn to be sensitive to the environment surrounding them. They will then be discerning in the appreciation

and preservation of buildings of merits. be discerning in the appreciation and preservation of buildings of merits.

You called on PAM to play the leading role in promoting aesthetic education. How relevant and qualified are we, as architects to undertake this task?

Our professional commitment is the deliverance of buildings of beauty to enhance our environment. At large, we are participating in shaping a beautiful and civilised nation where people go about with moral disciplines. Of course, PAM will have to seek collaborations from experts of other related disciplines such as educators who share similar visions.

How do you see art being infused with architecture?

When I see a plain wall or other surfaces, I have a compulsion of splashing colour or shaping some design features onto them. Yes, integrating art with architecture has been my passion from the very beginning to the later stage of my practice. An example of my early work was designing the façade of a house inspired by Mondrian’s non-objective composition of lines, planes and their interpenetration by engaging the dispersal of acrylic panels in three primary colours.

We saw how your love for art has been infused into your work in the video presentation entitled “Living with Art” which was shown at the end of your acceptance speech. It was about how you have created your house and lived in it for the last 30 years. Your concluding statement was, “All buildings of distinction possess the inherent qualities of integrity, discipline and grace. Each architect must seek his path to elevate his level of professional deliverance”. Please tell us how you have fulfilled these qualities in the design of your house.

Integrity: The design theme and its execution is entirely based on my inner thoughts, my esoteric awakenings, my love for the arts and my lifestyle. The resultant expression of the building is a true and telling story of “who am I”.

Discipline: In the creation of a stable structure to accommodate all levels of activities, providing all facilities and services and to allow for the activities and movements in and outside of the shell, I adopted a 4.2m square grid where columns are planted at this strict interval. This is my way of exerting discipline in design. Functional spaces, circulation spaces and living spaces are articulated by the introduction of brick walls, glass panels, stainless steel fins, resulting in a wholesome home of varying volume and ever-flowing space.

Grace: All parts of the building, all details of the building elements are thoughtfully detailed with aesthetic consideration, artworks of different shapes and dimensions find their appropriate space within the building, complementing the light and shades, rendering every corner of the house with the ambience of grace.

There is a saying “Never trust an architect who does not live in his or her projects.” You have walked the talk as you lived in your designs – the Hexagon, No. 8 Jalan Gurney and currently No. 369, Bukit Gasing. Would you like to comment on this assertion?

I find your assertion witty and candid. Nevertheless, I tend to believe that the best test of an architect’s skill is in examining how he designs his own home and observing how he maintains and lives in it. It is his intimate and ultimate testimony. It is not the volume of work he has done or how tall the structures that he has built. It is how his architecture carries the vision and wisdom of his thoughts that exerts influence onto others who come after him that distinguishes him from among his peers.

During your conferment, you highlighted that we should seek our moral values. One of the most poignant actions you took during your career was deciding on early retirement as you believed that your role was going against your moral values. Architects tend to believe that there is no end to our pursuit of passion in our career but your move to step away is very commendable. What are your feelings about having left the scene of the profession while it was still booming?

In the early ’90s, a young entrepreneur invited me to participate in a sizable housing development. While the project met with early monetary success, I found that our aspirations were not of the same tune. I was drifting away from the value in life which I cherished. This coincided with a time when my early interest in spiritual development began to hound me. I felt then that the time was ripe for me to move on.

With the bureaucracies, legal hazards and chaotic competitions and mounting complexities surrounding the practice of the architectural profession these days, would you have chosen to be an architect for the next generation?

The profession faces different challenges at various times and places. If it is your passion, it will be for you to overcome all obstacles to dedicate yourself to doing something you love best and can do best. My answer is, therefore, yes.

Lastly, would you like to advise the younger generation who are continuing and progressing the architectural profession?

Here is my gentle piece of advice to all young architects.

1 The greatest gift in architectural education is the opening of our vision to an infinite range of beautiful things. We should surround ourselves with the arts and nature in our daily lives, then our creativity must inevitably elevate to a higher plane. We will surely be in a constant state of bliss, and that should be the way of life of an architect.

2 Develop the primary skill which distinguishes us as architects from others; that is, the ability to put together materials to create and retain forms in space. It is better said by Mies Van de Rohe, quote: In architecture, we must deal with construction. When the structure is refined and becomes the expression of the spirit of its time, it can then and only then become architecture.

3 Architecture concerns itself as a social science. We must take on a responsible role in society in the improvement of our environment and making the world a healthy, beautiful and happy one.

4 As architects, we need to elevate our perception in life by invoking the spirituality which is latent within us. From within the cave of our heart, we should awake to the truth, to find that there are abundant reasons to celebrate life with joy and dignity.

Ar. Dato’ Lai Lok Kun’s perception of the profession is a breath of fresh air for both the young and old alike. His insights and experience of what was and what has become of the profession in Malaysia is an eye-opener and provides hope for the future of our profession. His words of wisdom will inspire many more generations in their pursuit of where their values lie and where their career should head towards.

His house of 30 years boasts his love and appreciation for art, a building that despite its age boasts timelessness and beauty at every corner. It is a blessing that the house, his labour of love is immortalised in a video curated beautifully by Victor Chin.It was an honour to be able to meet an architect of such calibre. For those who wish to have further insight into his thoughts and history, look forward to the release of his memoir in the near future.