My parents were both trained as teachers in Kirkby in the 1950s. Their art teacher there was none other than Syed Ahmad Jamal.

I grew up in a house filled with my father’s oil paintings and Chuah Thean Teng’s batik works, which I had an affinity with because my Nyonya grandma from Penang always wore beautiful batik sarongs.

I would like to think that my collection is quirky, inquisitive and beautifully fun.

My life and professional journey to date have given me periods in Australia, Indonesia (in particular Bali), Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Sri Lanka and so I have works from these countries. I’ve found art to be a wonderful expression of the culture, context and times that I’ve lived in. So, in that sense, my collection is a story of who I was and who I am.

DTLM

In my work and travels, I try to include one or two places to help me stimulate the inner man, something inspiring and intellectual, mind-boggling is even better. So, I check out the new architecture to visit or the latest exhibition in the museums. But I found this missing in Malaysia. I am mindful that a bankrupt culture or civilisation is devoid of great architecture and art.

Some years back during my more energetic youth, I embarked on a project to address this problem. I used to own a strategic piece of property in Bangsar where I wanted to build a contemporary art museum for Kuala Lumpur (KL MOCA). This project went all the way to building approvals and even commenced construction. Unfortunately, it did not get any further and is today the new PAM Centre. Ever since I had been looking for a new location to fulfil this dream.

In the intermittent period, life seems to have changed with the advent of Instagram. I noticed in my travels that smaller, more focused museum spaces where one can book a visit online, enjoy the show, buy a souvenir and have a coffee all within an hour had become the new normal.

I think Malaysia could do with small focused and well-curated spaces with a strong narrative. And something that normal people can understand. For this moment I feel that art needs to come down a bit from its ATAS high horse.

DTLM

Ur-Mu is housed in a refurbished old 5-storey walk-up apartment block with 10 small themed gallery spaces. It was designed to stand out and excite but yet fit into the scale and context of the neighbourhood. It will house 60 to 70 selected works from my private collection.

The first works visitors will come to is a large photographic lightbox work entitled the Feast by well-known Hong Kong cinematographer Wing Shya and The Precious Wedding by Jailani Abu Hassan, also based on a feast, which captures many of my friends from the art world.

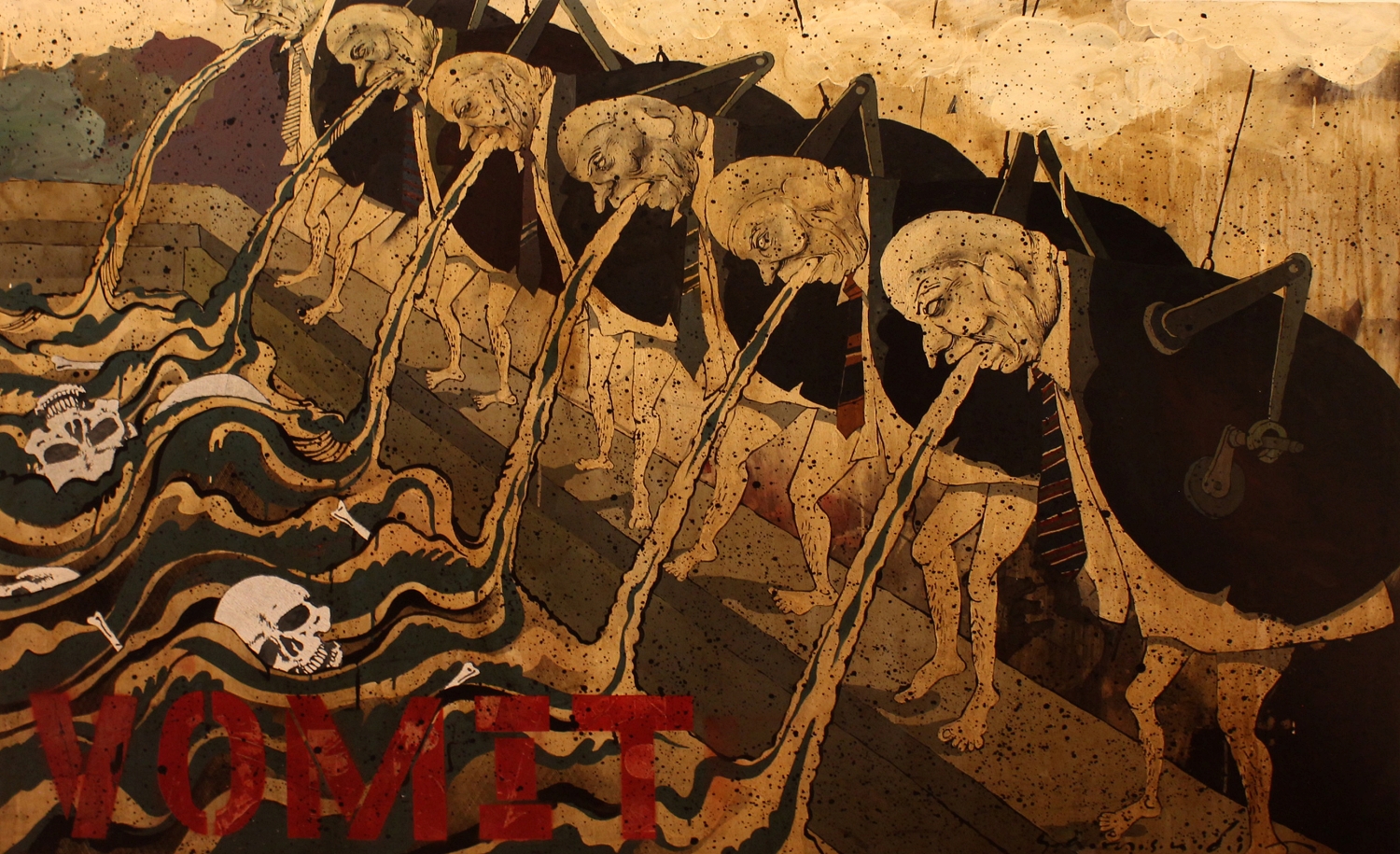

Other highlights are Tan Zi Hao’s Myth of the Makara, new artist Atirah Zuraimi’s Death to Craft and Samsuddin Wahab’s Wira Bangsa series on the environment.

Some of the gallery themes are Street Life, People, Our Living World, Power Play, Raksasa (Monsters), Save Me, Ultraman!, Obscura, Modern, Bali-Days and, of course, Architecture. There is also a modern sculpture rooftop garden and a Balinese garden commemorating an old friend, the late landscape maestro from Bali, Pak Made Wijaya.

DTLM

LT

How did you start collecting? Is there a particular way you like to collect?

LT

In the early years working back home here in Kuala Lumpur, I’d go for exhibition openings to look at local artists’ works, though often I couldn’t afford to buy.

I cringe a bit when people call me a collector. When you buy something because it’s beautiful and you want to enjoy it, you never think you are becoming a collector. It’s quite natural for people to want to surround themselves with things that give them joy. I’m not the type who goes searching, looking out for that exhibition, is always the first one to buy, or who collects to invest.

Being an architect makes me look for the things that I value in architecture, in an artwork. It must be something that gives me great aesthetic pleasure from the usual proportion, colour and of course, for a painting, the rendering and brushwork. For me, the mark of quality of a work is also how well-crafted it is. You’re talking to a traditionalist.

Even if a work is visually clever, I find that if it’s poorly made, I cannot buy it. These conceptual artists who just throw a slab of rotting meat in a glass box and throw it in a museum – I’m not a big fan of that sort of work. As for abstract paintings, in art history class where we learned about works by these great American abstract artists, I would wonder, beautiful as they are, if they were meant more to fill those big walls of Modernist glass houses.

LT

LT

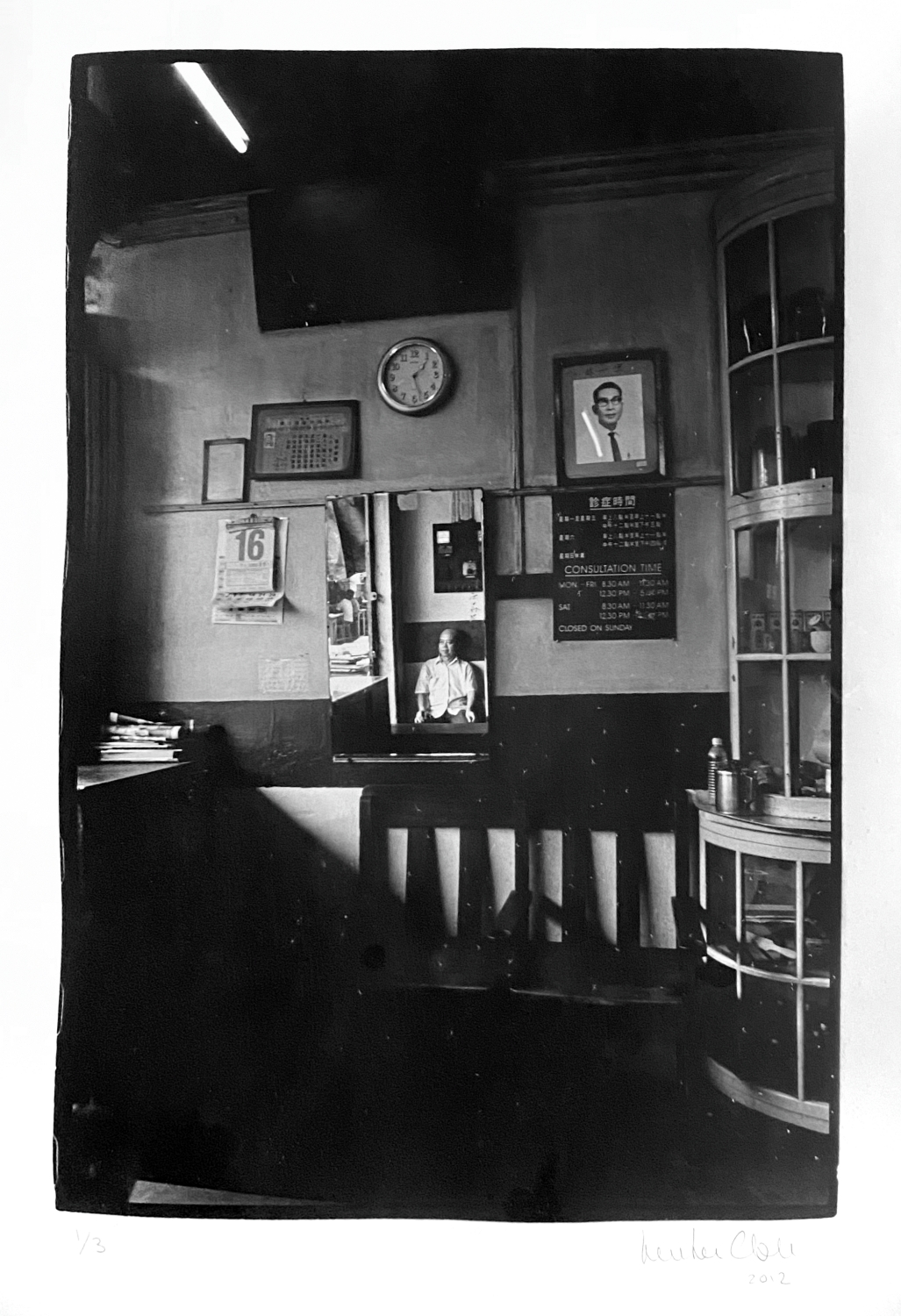

Early on, I bought Yau Bee Ling’s paintings from Pelita Hati Gallery, which I happened to live nearby. At that time, I really liked figurative work with a strong narrative; I liked the story that you have to piece together from the painting. I bought her beautiful early drawings as well.

Some artists make very good works in their early years, which are often more intuitive before they are out competing with other artists. There are some wonderful works you can pick up from students or new graduates. The first major acquisition must be Anum’s (Noor Mahnun Mohamed’s) The Wasp (1995). I had no idea who this artist was, had never seen this work, this hand before, and it was just so stunning and well-made. That was in 1999, she’d just returned from Germany and it was her first exhibition, at Galeri Tangsi. I do consider Anum an artist who crafts her work very well. I also love the painting because of her rendering of light, although of course, it’s not a very tropical light.

Anu (Anurendra Jegadeva) has always been a good friend, but it was hard for me to collect his earlier works because of the angst and politics. I was glad when I finally saw a peaceful piece, the portrait of his daughter, with the rough sea and the small boat in the background. Most Sri Lankans, when they emigrated to Malaysia, came on that one ferry that shuttled across the Indian ocean. I just loved his celebration of that story.

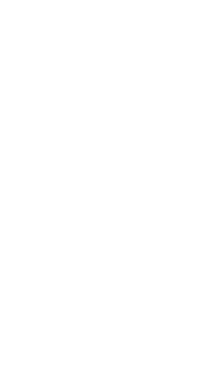

I didn’t realise I had so many works that depict the female figure. It wasn’t intentional. I didn’t have this feminist idea that I’m going to buy work by female artists or female stories, but just unconsciously or subconsciously, a lot of my paintings depict women in some way.

I have a cast bronze sculpture by a French artist, bought on holiday, and sculptures by a German sculptor Hilmar Habbeck, who made them by hand from Ipoh marble. Artists rarely make cast bronze or stone sculptures in Malaysia.

LT

One of the earliest works I bought was by the great Eric Peris – I’d always loved his landscapes, his tin mines. Lina Ang, the woman in the photograph, was one of the early contemporary dancers, doing Butoh.

I was always interested in photography because I’d also practised it.

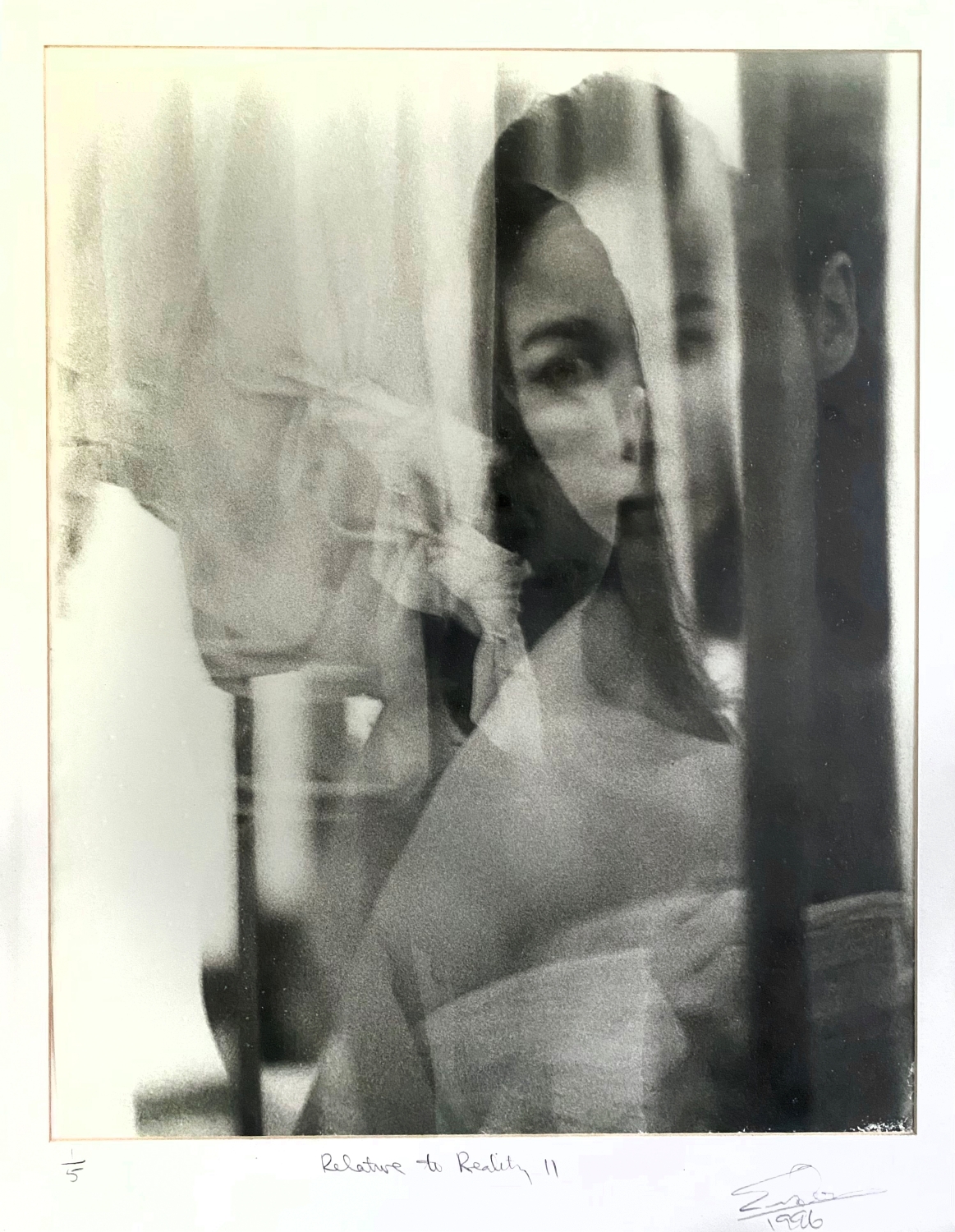

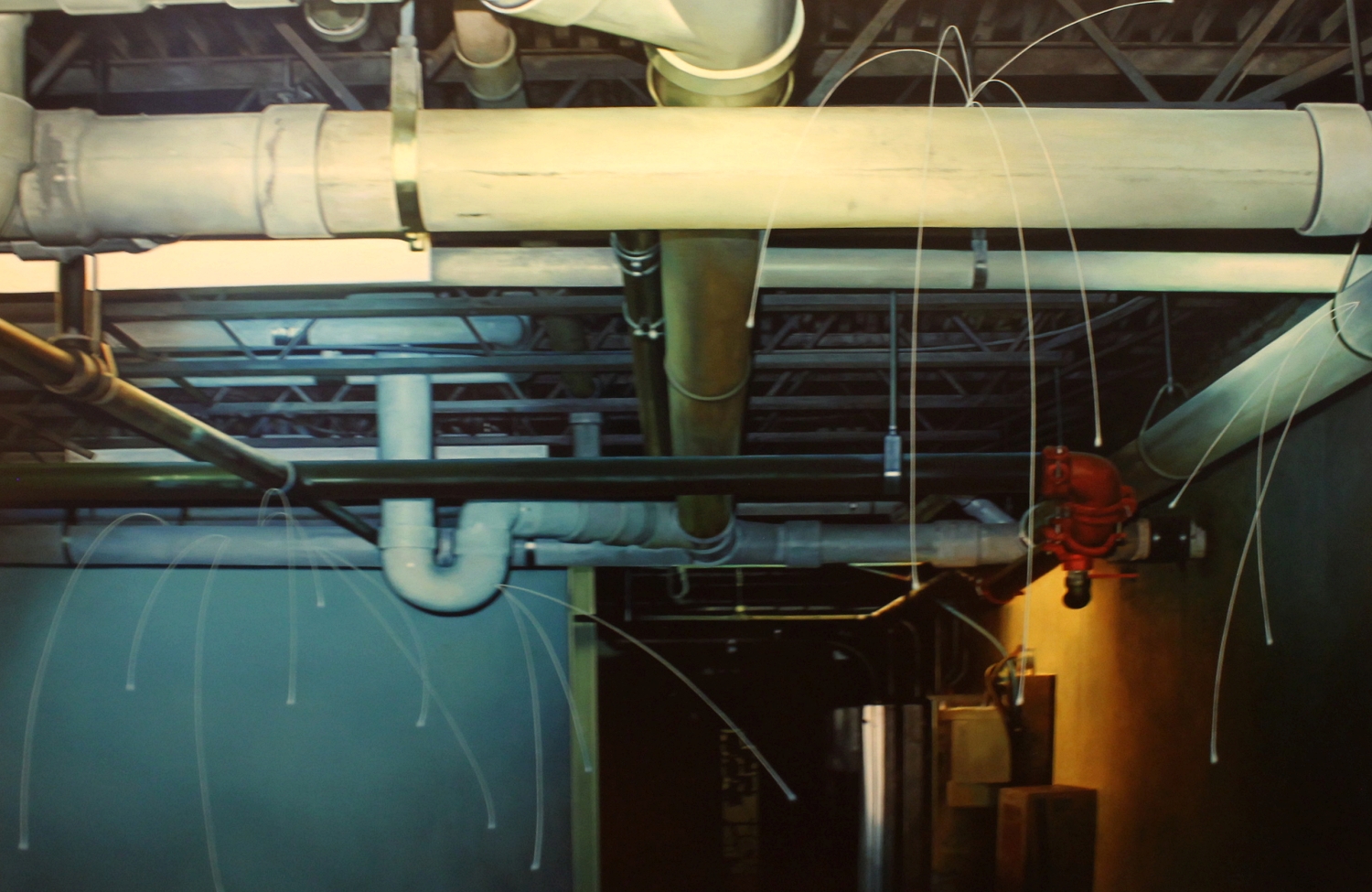

Before I had Temu, the place was used by a group of classical film photographers. I set up a dark room and a gallery in this 1960s house. It was called The Print Room, and it ran for nine years. A few young people came and learned the art of film photography. I always thought I’d go back to it myself, but unfortunately not. With the demise of traditional photography, the film and chemical companies closing, they eventually packed up. They found it hard to sell their work – a lot of people think reproducible art is not true art and does not involve the direct hand, and feel uncomfortable with the idea of fixed multiple ownership of an artwork. And with handphone cameras, everyone thinks they are photographers.

I was with Badan Warisan for some 10 years as a heritage advocate. As an architect, I was interested in the city, and in documenting the old, disappearing city. I curated a photography exhibition at the National Art Gallery celebrating Kuala Lumpur’s 30th birthday in 2002. I encouraged the group at The Print Room to photograph our beautiful dying wet markets, old streets, old churches, missionary schools, colonial buildings in Penang, Malacca and many small towns in Peninsular Malaysia.

LT

Every year, the local authorities usually set aside a good budget to paint and landscape their older public housing projects, many of which are in dire need of maintenance. Latheefah Koya, whom we worked with on the project, was an MBPJ Councillor then. One day, Wong Hoy Cheong popped in and said, I need your help to come up with some painting colour scheme for these flats. But it wasn’t really about painting, it was about ownership. And so, we decided, instead of us deciding what to paint on it, we’d let the residents choose. It wasn’t about the colour scheme it was about giving people a sense of control of their environment.

Around 2006-2007 Veritas had also worked on documenting the Pekeliling Flats before they were demolished. I wanted to do an exhibition of this early public housing from the 60s and the stories of the residents we interviewed. Many of them had moved in during the May 13 period. Photographer Sharon Lam made portraits of the remaining residents resisting the demolition and we did some measured drawings. When the flats were emptied, you could see everyone used different colours because that was their means of expression.

At Maju Jaya, we also looked at what was wrong with it – poor security, there being no place for kids to play. We helped the community realise some very simple things – like getting motorcycles out of common courtyard areas, creating a sense of entry to the buildings. It involved architecture and community planning more than “art”. So it was an exercise that started with a lot of paint given to an artist, and then we turned it into a community project and a commentary on public housing.

And community planning and ownership have become a big part of how Hoy Cheong approaches art practice. Maybe there is room for thinking more about how architects, artists and urban communities and spaces can intersect. This brings us to Temu House – can you tell us something of how this began and plans for the space?

LT

After the photographers left, the house was empty. My friend, Lina Tan wanted to make a safe space for women’s groups for their events. During the pandemic, a lot of people have been catering from home and so she also thought to make the space a pop-up kitchen for these women trying to make a living. I just cleaned up the space for them, dismantled the darkroom, expanded the pantry into a kitchen.

The gallery space was already there for the photographers, but it’s now also a space for private events. I’m not so involved in the art exhibitions. Our opening show at Temu was a show of women collectors that was the curator Sharmin Parameswaran’s intent.

The emphasis is on women entrepreneurs, women artists, women’s efforts. I think that’s good. I’ve had such a challenging time in my industry because there are not enough women who stay the course. You seldom get the benefit of the doubt. There are so many young people wanting to do things. It’s just the beginning. It’s very flexible. It’s not meant to be a profitable project, more as a way to help people gather.

NS

My interest in contemporary art started during my 12 years in New Zealand. My boss then, Don Miskell, was an art collector. I bought my first artwork here, a print by Graham Bennett – that print inspired my company logo five years later.

Working in Singapore from 1990 to 1994, I was involved with the active art scene there, visiting galleries, and happenings by The Artists’ Village led by Tang Da Wu, and Suzann Victor’s 5th Passage, such as at Hong Bee Warehouse. I made friends with many of the artists.

When I returned to KL to start my consulting landscape architectural firm, I decided to collect the works of local artists. Believing that artists are the avant-garde of visual thinking both in terms of material and philosophies, we hoped that our conversation and interaction with their works would influence and advance our landscape work.

We dedicated 10% of our office profits to collecting young emerging Malaysian artists. In certain years that increased to 25%. The first work we collected in 1994 was a painting by Bayu Utomo Rajidkin called The Afghan Boy. The artists we began collecting in the ‘90s were Bayu Utomo, Yau Bee Ling, Chuah Chong Yong, Wong Chee Meng, Ahmad Zakii Anwar, Wong Perng Fey, Anthonie Chong, Jai, Ivan Lam, Phuan Thai Meng, Tajuddin Ismail, Raja Shariman, Shia Yih Ying, Yusuf Gajah, Wong Hoy Cheong, and others who have disappeared from the art scene. There were very few private art collectors in those early years.

NS

When we had our collection documented five years ago, we had just over 500 works.

Looking back at this eclectic collection, one characteristic thread is works that tell stories of the tumultuous period between 1998 till today. I’m retired now and have less income, so the collection has substantially slowed down too, but I do nibble occasionally, especially at works by artists I have been collecting consistently if they’re still affordable, or at works that help fill in the gaps of this “reformasi” collection.

The collection, mainly housed in Sekeping Tenggiri, is accessible to the public. I see myself only as a temporary custodian of these artworks, whose lifetime and importance will outlast me.

NS

Many artists, architects and designers have influenced our landscape work. At the beginning of my career, our works were heavily influenced by Martha Schwartz, a fine artist turned landscape architect who uses very unconventional materials to compose her landscape, including bagels and plastic frogs. Christo, Wong Hoy Cheong, Ron Arad, Che Guevara, Olafur Eliasson, Stephen Covey, Masanobu Fukuoka, EF Schumacher, and many others were early influences.

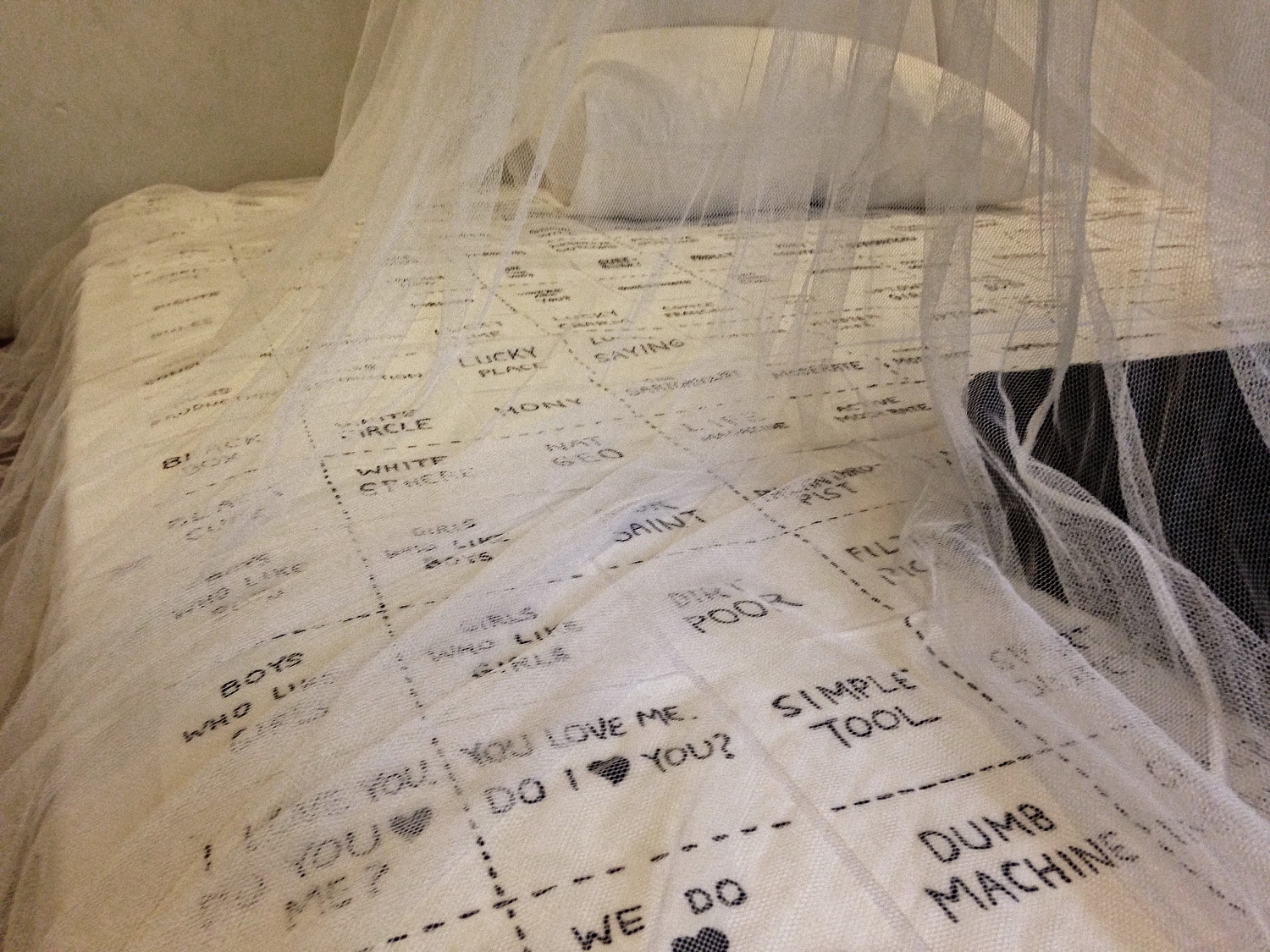

We collaborated with New Zealand sculptor Neil Dawson (for Jalan Pinang Wisma Perkasa, 1995) and Lat (for Kampong Warisan condominiums 1994), and adopted Wong Hoy Cheong’s strategy of using text to bridge the divide between common viewers and our more abstract landscape works (Melaka Multimedia University and Wisma Perkasa floor texts, 1996).

Art making is an extremely tactile activity. My venture into making non-useable objects has also informed my professional practice. It is about returning to a more craft-based tradition of practice, beyond mere business.

NS

In 2004 when I designed our office, I left the ground floor open as an ‘art’ space. I was hoping to have artists come to use it, and have my architects/designers interact with them. We also realised that there were not enough venues where artists could experiment and show works that had little commercial value, such as performance and installation works, so our space at 67tempinissatu helped fill the vacuum at the time. As more venues started to come up for visual art, the space became more often used by writers.

I believe our maturing society must be immersed with art, music, theatre, comedy, food, to enrich our urban lives. I believe as someone working in the construction industry, I must always allow arts to come into our space, and I should create such opportunities in my daily undertakings. KongsiKL and kebunkebunbangsar, for example, are about taking underperforming resources and redistributing them to those who most need them.

How has the art scene changed over the past 20 years? What’s exciting about the current scene? Do we need more space for art and what kinds of spaces? What would you like to see happen?

NS

In the last 20 years, there have been a lot more buyers for visual art for reasons ranging from pure artistic appreciation to financial investment and speculation. This has created opportunities for young artists to survive and become full time. A large amount of artwork has been generated, which I consider being a very positive development. What is even more exciting is the expansion into the digital realms of new media and animation and NFTs by younger artists. Also exciting is the expansion of the ancillary industry of art-making, including the increase in numbers of writers, curators, art tourism, auctions, fairs, publications, placemaking, festivals, private museums, community organising, etc.

I hope the practice of moderate prosperity, with our realisation that the world is enough for our need but not our greed, will lead us to not more art spaces but rather more art in public spaces. I hope that all the failed shopping centres will soon be converted to art spaces and learning centres, and that, with robots and AI taking over our jobs, more of us are paid a basic universal income to indulge in art and art-making.