Sometime around a Covid lockdown last year, we were approached to craft an interior for a condominium in Damansara Heights, Kuala Lumpur. The design narrative leads one through a journey from pre-historic to modern Malaysia. Of course, the arts and crafts of Borneo could not be left behind in her formation – pun intended.

In the process, I met an anthropologist and lecturer, Dr. Welyne Jeffrey Jehom, who works closely with the Iban community of Sarawak. One such community lives in the longhouse of Rumah Gare(h) located in Sungai Kain, Kapit.

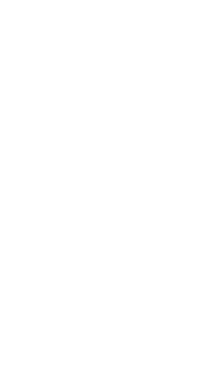

Among the up to 28 sub-ethnic groups, Iban is the largest native community in Sarawak. They belong to a branch of the Dayak people and are quoined by the British as Sea Dayaks.Pua Kumbu is an art form dating centuries old but the specifics remain unknown. One mythology points to a jacket and cloth (baju burong and kain) made by Dara Tinchin Temaga from the godly world for her human husband and son to return to earth. This is poetically seen as the Ibans’ connection to the gods.They are ceremonial blankets for Gawai, weddings, wrapping a newborn, collecting heads of victims (historically Iban men were head hunters) and draping on the deceased; acting as symbolical boundaries and protection.

Weavers are almost always women passed down from the matrilineal line, although men do support to a certain degree in preparation works.In earlier times, Puas were reserved for the community and their cultural practices only. They were not intended to be shared with the outside world. However, due to sustenance and the digital economy, the Iban community is embracing the trade of this rare art form.

SUBSTRATES

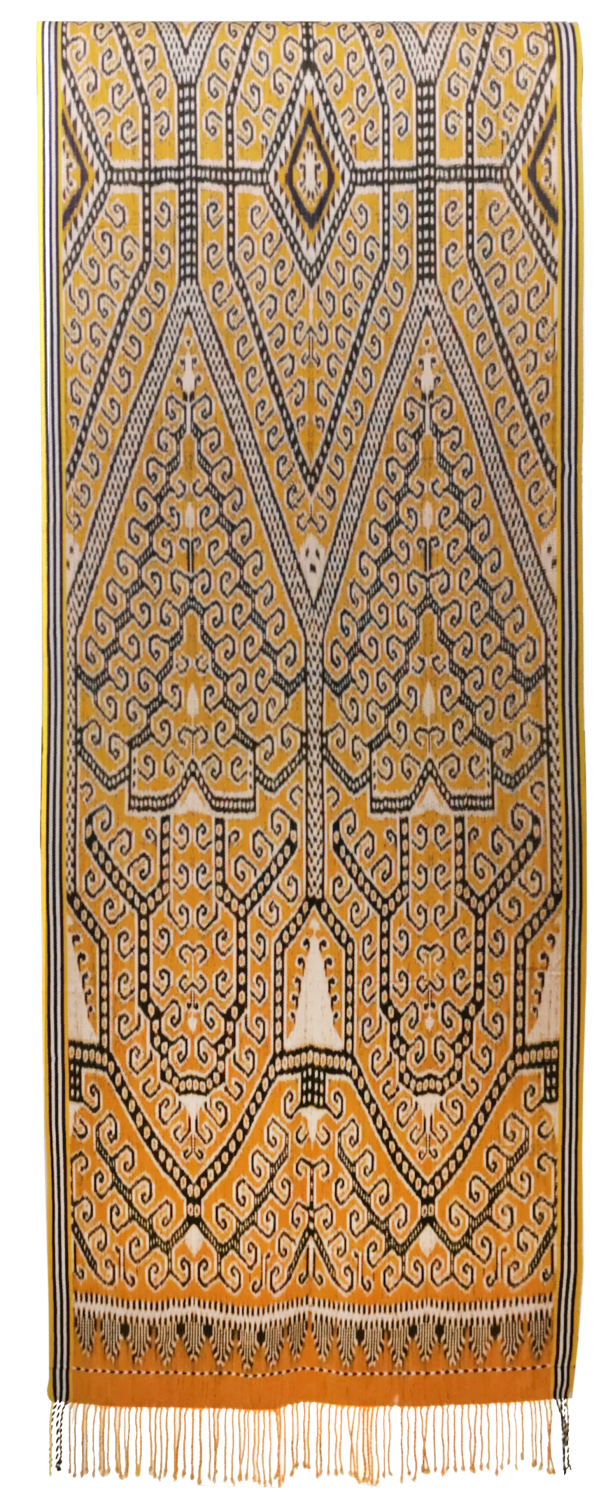

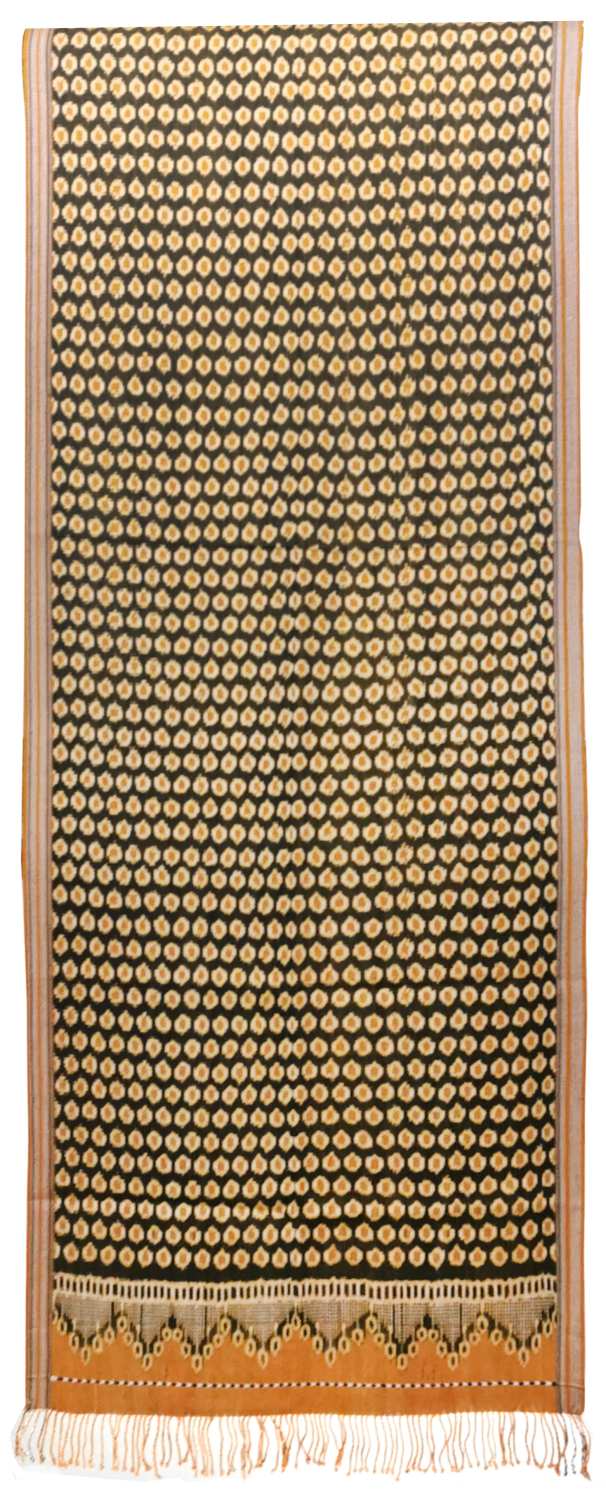

The duration to complete a Pua of approximately 600 x 2000mm (width x length) takes two to three months. Each is woven on a back-strap loom, typically cut at a horizontal mirror-line, then sewn together lengthwise to form a wider textile of approximately 600mm wide.Designs originating from Rumah Gare(h) will only see two of the same design woven by one weaver, although they are never perfectly identical. This is due to the uniqueness of their craft involving manual tie-dyeing and weaving amongst other reasons, making their hand-made appeal highly coveted.

On careful examination, the patterns carry a weaver’s signature but also demonstrate seniority of skills, ancestral lineage and even inspired by their dreams foretold by the Gods and interpreted as permissions granted to weave specific motives.According to researcher Van Hout, most motives found in Puas are anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, or representations of flora and fauna, and geometric patterns.

Subjects of Pua Kumbu are not always defined and only known to the weavers themselves. However, not all Puas have a name either.When asked to translate the titles of selected Puas, Jehom stated not every piece could be translated or explained by laymen. She advises they remain in their original titles and not to err on misappropriation.Many textiles which ended up in museums and with collectors have their origins, animistic beliefs and meanings lost, making provenance rather impossible.

Challenges currently faced by the Iban community are the lack of access to public amenities and utilities to serve their longhouses. This inadvertently leads to an exodus of their younger generation for better livelihoods in urban centres, hence leaving this artform behind.

Deforestation is also partial to the propensity for synthetic dyes, which not only breaks away from their authenticity but are difficult to match with traditional dye colours and cause harm to the natural environment.Other timesaving means also include purchasing commercial yarns as opposed to growing and spinning their threads. The quality of Puas is inevitably compromised with the introduction of commercial and synthetic materials.

Christianity and other Abrahamic religions present challenges to continue the animistic beliefs and practices of the Iban community. As Jehom states, “It has become increasingly difficult to continue this practice due to their complexity of animistic beliefs, which follow strict taboos that contradict Christian practices.”However, a handful of Christian-Iban weavers including the master weaver of Rumah Gare(h), have syncretised their religion with the traditions of making Pua Kumbu.

The survival of this labour-intensive and highly skilled art form remains precarious. A cultural instrument and an artform fused by nature (the universe) and the spiritual world, Pua Kumbu represents a bridge connecting present times to the past, one that will hopefully live on forever.